Mar 19, 2025

Soil Health: Biological Diversity

Soil is a natural component of terrestrial ecosystems, both native and agricultural. Soils are the foundation of plant and crop production systems (Brady and Weil, 2008; Parikh and James, 2012).

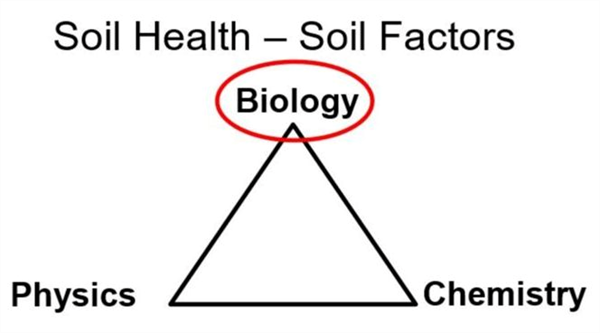

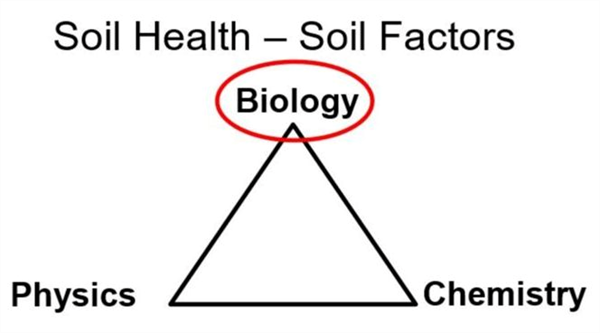

In terms of soil health, a good way to consider a soil system is from the standpoint of three main categories (physics, chemistry, and biology) that are fundamentally important with healthy soil function (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Soil health factors and chemical properties.

It is estimated that soil contains at least a quarter of the biological diversity (aka biodiversity) on our planet. Soils are second only to the oceans in terms of biological diversity. Billions of earthworms, nematodes, insects, fungi, bacteria, actinomycetes, viruses, and other invertebrates exist in soil naturally. These creatures produce and consume the organic material (i.e., crop residues) found in soil as part of their basic fund and collectively work to break down the organic materials that come from their bodies and plant materials into minerals and nutrients that are cycled in the soil system and support healthy conditions in the soil environment, including plant nutrients.

During the 20th century, soil scientists began to better understand the complexity of soil biology and ecology. From that work, many drugs and vaccines have been derived soil organisms. For example, antibiotics such as penicillin have been developed. Treatments for cancer such as bleomycin have come from soil and fungal infection treatments like amphotericin have also been derived from the soil microbiome. Accordingly, the biodiversity of soil still has a huge potential to provide new drugs that can help us in combating other illnesses and dealing with pathogenic and resistant microorganisms.

This tremendous biological diversity creates the foundation for the entire soil ecosystem. Soil ecosystems impact the growth of plants and animals in natural and agricultural systems. The biological composition of soils has a very strong influence on soil health.

During the 20th century soil scientists had an appreciation for the rich biological diversity in soil but they were limited in their analytical capacities (Waksman, 1936). In the past 40-50 years, soil scientists have employed an increasing level of new analytical tools that have allowed the discovery and better understanding of the number and diversity that naturally exists in soil (Sutton and Sposito, 2005).

A good description of biological diversity and its tremendous complexity can be demonstrated by consideration of the common composition of soil and the abundance of a few classes of microorganisms in one gram of soil (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Natural abundance of bacterial, actinomycetes, and fungal organisms in one

gram of soil.

It is incredible to realize that in one gram of soil there commonly exists nearly one billion individual bacterial organisms, more than a million actinomycetes organisms, and one million fungal organisms. All these organisms naturally exist in soil and these population numbers represent just one gram of soil!

Among the approximately one billion individuals in one gram of soil, there are commonly more than 10,000 different species. Soil biologists are now working to better identify individual organisms and understand their functions individually and how they function in the complexity of the soil ecosystem. We do not know all the species. Accordingly, we do not know how all these organisms are forming and functioning as a complex ecosystem. Soil ecology is a huge and rapidly expanding area of study.

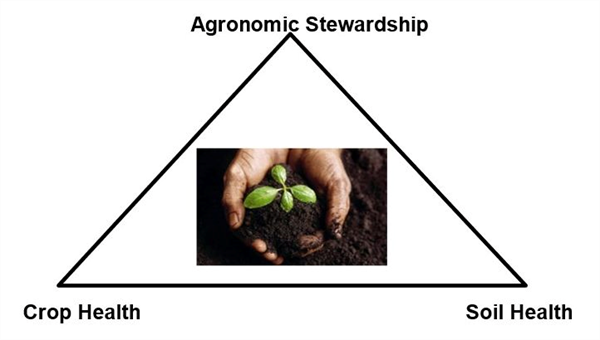

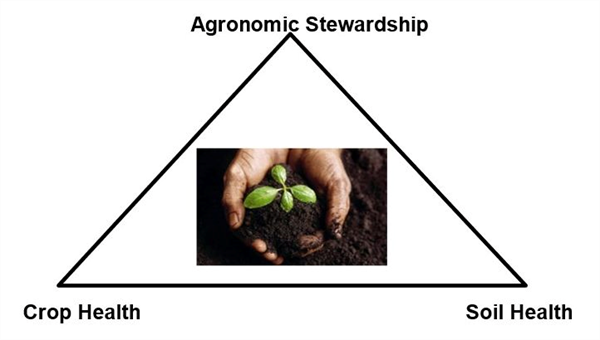

We do know that soil biology and ecology are very important aspects of soil health (Figure 1). We also know that our management in the field, agronomic stewardship, has a strong influence on soil health and accordingly crop health.

Gaining a better understanding of soil health requires a better understanding of soil biodiversity and the functioning of soil ecosystems. It would be misleading to say that we have a solid understanding of the soil ecosystem function and all the managerial relationships. However, it is important to understand that working on this frontier of soil science and agriculture is critical to our efforts to maintain sustainable and productive agricultural systems for the future.

Figure 3. Interrelationship of agronomic stewardship, soil health, and crop health.

To contact John Palumbo go to: jpalumbo@ag.Arizona.edu

To contact John Palumbo go to: jpalumbo@ag.Arizona.edu