Sep 20, 2023

Management Proposals for Colorado River Water

As Colorado River flows have decreased over the past 23 years due to the prolonged drought, many proposals have been presented for management of the river. One group from the research community presented some intriguing scenarios last year with a publication in Science on 22 July 2022 (Wheeler et al., 2022).

I found some of their points and suggestions interesting in relation to the Colorado River management discussions. These recommendations are not reflected in the recent U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) operational plans for 2024 that were presented with their 24-Month study reports and projections (USBR, 15 August 2023). It will be interesting to see if these points become part of the negotiations in the next two years for the interstate and international shortage agreements that expire in 2026.

Basic parameters for any proposed management plans of the Colorado River must include the “Law of the River” which is an amalgam of interstate compacts, court decrees, federal laws, secretarial guidelines, and an international treaty with Mexico. Key elements associated with the Law of the River include the 1922 Colorado River Compact among the seven basin states in the United States and the 1944 Treaty between the United States and Mexico.

The 1922 Colorado River Compact divided the watershed into upper and lower basins with the dividing point at Lees Ferry in Arizona. Each basin was allocated 7.5 million acre-feet (MAF) per year. The 1944 Treaty established a delivery requirement of 1.5 MAF/year to Mexico. Thus, a total of 16.5 MAF/year is allocated from the Colorado River.

The 1922 Compact negotiators based their work on an assumption of 17.5 MAF/year of river flow. However, the 20thcentury average natural flow rates on the Colorado River have been 15.2 MAF/year, resulting in an approximate 2.3 MAF/year structural deficit. This deficit in the water budget for the Colorado River and evaporation losses were never corrected in a formal manner, primarily due to some states not using their full allocations.

Changes in the climate since 2000 have resulted in much drier conditions in the Colorado River watershed with reduced annual natural flows to an average of 12.3 MAF/year. Thus, the challenge in addressing the shortages on the Colorado River is that of basic mass balance and developing a consumptive use water budget that matches water supply in the river.

Like many people working in agriculture, I have been watching and studying the situation with great interest. Based on my understanding, one of the key issues in the negotiations has been the differences in perspectives between the upper and lower basin states.

The lower basin states and Mexico have been fully utilizing their water allocations from the Colorado River in contrast to the upper basin which has not been using its full 7.5 MAF/year allocation. For example, between 2000 and 2020 the upper basin consumptive use averaged 3.7 MAF/year plus at least 0.7 MAF/year of reservoir evaporation. The upper basin states have plans for further development and utilization of their full allocation and they want to protect their Colorado River water allocation to support these development plans.

Agriculture is responsible for approximately 70% of the Colorado River water use. As noted by the USBR (2015), the lower basin has been irrigating less than one-half of the area irrigated by the upper basin, but the agricultural revenues of the lower basin are more than three times that of the upper basin.

Additional upper basin development and water use from the river exposes a much higher level of uncertainty on Colorado River water management for the future and there are concerns that it could violate the non-depletion obligation in the 1922 Compact which states the upper basin will not deplete the river’s flow to less than 75 MAF during any 10-year consecutive period. This implies an assumption on the part of the 1922 Compact negotiators that a short-term drought could be managed within a 10-year period, but we are now dealing with drought extending over 23 years. In addition, the 1944 Treaty requires all seven states to share in the obligation to Mexico.

The upper basin states have been adamant that the responsibility of balancing the shortages on the river rests fully with the lower basin states and Mexico. The upper basin states have also consistently emphasized the importance of equality between basins as outlined in the Compact but that has not actually happened in 100 years.

The upper basin representatives have proposed reductions in lower basin water use of 1.2 – 1.5 MAF, which is a reduction of about 17-22%. In addition, upper basin states suggest that evaporation losses from the river system should be subtracted out of the lower basin allocations.

On the other hand, important economic and equity considerations must also be recognized and a good argument exists that the loss of an established agricultural industry in the lower basin is much more harmful than reducing plans for future development in the upper basin. Thus, the proposed development in the upper basin is being questioned and appropriately so in my view.

Wheeler et al. (2022) ran a series of hydrological models, including the USBR Colorado River Simulation System (CRSS, 2021) and developed a set of 100 scenarios. More details are provided in their article (Wheeler et al., 2022).

In my review of the work presented by Wheeler et al., there are two scenarios that are particularly intriguing, outlined in Tables 1 and 2.

|

Basin

|

Proposed Consumptive Use

(MAF)

|

Percent of Full Allocation

and Reduction.

|

|

Upper

|

4.5

|

60% of full allocation and0.8 MAF > recent use

|

|

Lower

|

6.0

|

66.7% of full allocation

(33.3% reduction)

|

Table 1. The first scenario presented in the Wheeler et al. (2022) article.

|

Basin

|

Proposed Consumptive Use

(MAF)

|

Percent of Full Allocation

and notes.

|

|

Upper

|

4.0

|

53% of full allocation and0.3 MAF > recent use

|

|

Lower

|

7.0

|

77.8% of full allocation

(22.2% reduction)

|

Table 2. The second scenario presented in the Wheeler et al. (2022) article.

Both scenarios represent significant reductions in Colorado River water allocations to balance consumptive use with recent natural flow rates. But the fact remains that the mass balance of natural Colorado River flow and consumptive must be dealt with to realize a sustainable system of management. All these scenarios present major challenges in implementation.

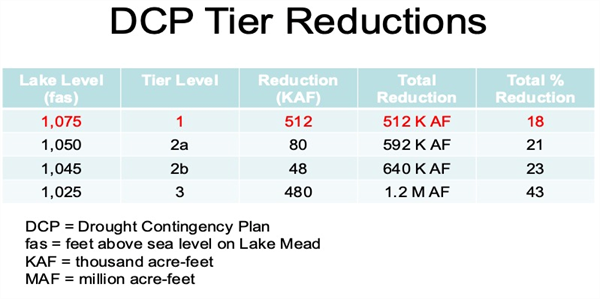

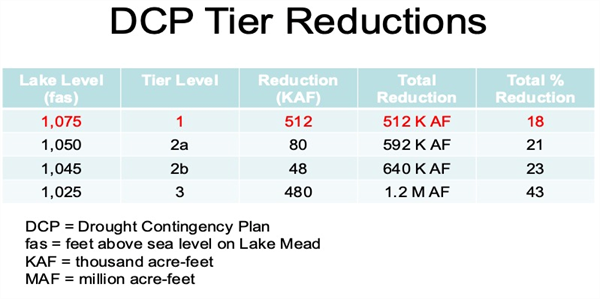

For 2024, the operational plans for the Colorado River are basically the Tier 1 plans from the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan (USBR, 2023; Table 3). Tier 1 reductions include an 18% reduction in Colorado River water use by Arizona and approximately 3 MAF of additional water is being held in Lake Mead by voluntary reductions from several Arizona municipalities.

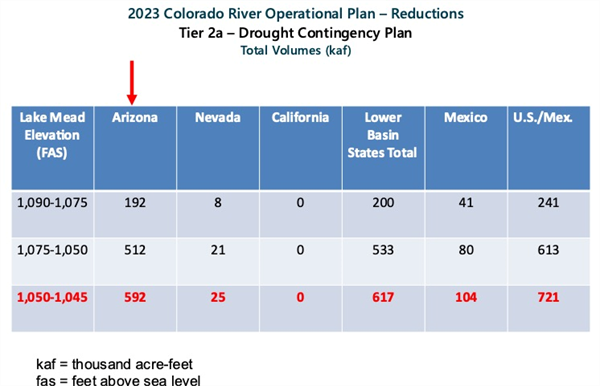

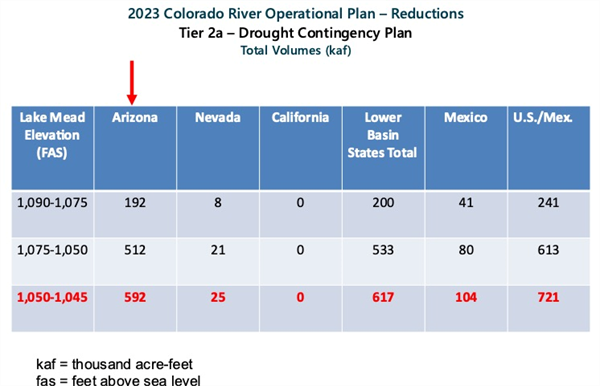

In 2023, Tier 2a guidelines were in effect in 2023 and Arizona has been dealing with a 592,000 AF allocation, which is a 21% reduction of the 2.8 MAF full allocation (Table 4). Thus, Arizona, Mexico, and other lower basin states have already been meeting the reduction requirements outlined in the second scenario described above (Table 2).

Table 3. Drought Contingency Plans (DCP) for Arizona, Tiers 1-3. Tier 1

reductions (red) will be in place in 2024.

Table 4. Drought Contingency Plan for lower basin states and Mexico, rows are

Tier 0, Tier 1, and Tier 2a. Arizona is highlighted with the red arrow and Tier 2a

for all lower basin states and Mexico in red letters.

The consideration of scenarios such as the ones described by Wheeler et al. offer some good points for consideration over the next two years as all interstate and international shortage agreements expire in 2026. The negotiations in the next two years will be challenging and any proposal offered will meet resistance, particularly under the conditions of the Colorado River after 23 years of serious drought and the high level of demand that exists in the basin.

Reference

USBR. 2015. “Moving Forward Effort: Phase 1 Report” (DOI, May 2015); https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/programs/crbstudy/MovingForward

USBR. 2021. “DRAFT CRSS: Key modeling assumptions, June 2021 model” (DOI, 2021); http://bor.colorado.edu/Public_web/CRSTMWG/CRSS.

USBR, 15 August 2023. 24-Month Study reports.

August 2023 Lake Powell and Lake Mead: End of Month Elevation Charts

Wheeler, K.G., B. Udall, J. Wang, E. Kuhn, H. Salehabadi, and J. C. Schmidt. 2022. What will it take to stabilize the Colorado River? Science, 377 (6604), DOI: 10.1126/science.abo4452

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abo4452c