Apr 3, 2024

Bacterial Wilt of Cucurbits (2024)

As we wrap up lettuce season and move towards melon season, bacterial wilt of cucurbit is a disease we have to keep an eye on. Couple of years ago we had high incidence of this disease in fields.

Bacterial wilt is a common occurrence in commercial fields and residential gardens. This destructive disease can potentially result in complete crop loss even before the first harvest. Hosts Cucumber and muskmelon (cantaloupe) are highly susceptible; squash and pumpkin are less susceptible; watermelon is resistant.

Initially, individual leaves or groups of leaves turn dull green and wilt (Figure 1), followed by wilting of entire runners or whole plants. At first, plants may partially recover at night, but as disease progresses, wilt becomes permanent. Collapsed foliage and vines turn brown (necrotic), shrivel, and die (Figure 2). Wilt symptoms may be noticeable in as few as 4 days from infection on highly susceptible hosts but can take up to several weeks to become evident on crops that are less susceptible. Plant growth stage can also affect disease progress, which is more rapid on young, succulent plant tissues.

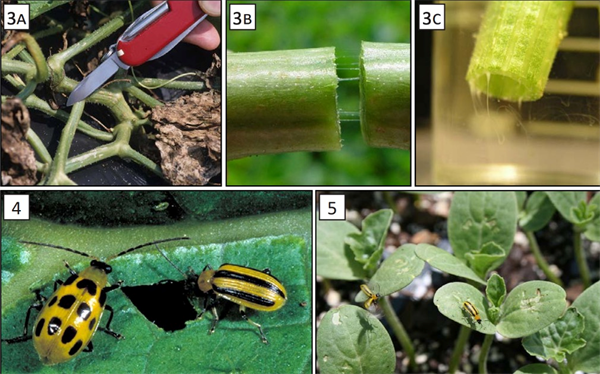

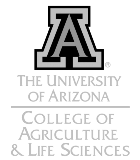

The diagnostic feature for this disease is the emission of a slimy, sticky ooze (exudate made of polysaccharides and bacterial cells) from cut stems. Field diagnosis can be confirmed using a simple “bacterial ooze test.” With a sharp knife, cut through a wilted (but not dead) vine; use a section near the crown (Figure 3A). Touch the cut ends together, and then slowly pull them apart. Fine thread-like strands of bacterial ooze will be drawn out (Figure 3B) when bacteria are present. This test works well for cucumber and muskmelon but is less reliable for squash or pumpkin. If this disease is present, a cloudy string or mass of bacterial ooze will flow into the water from the cut stem pieces (Figure 3C).

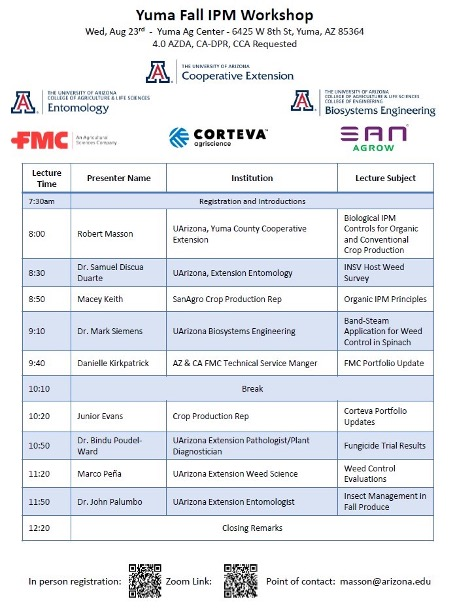

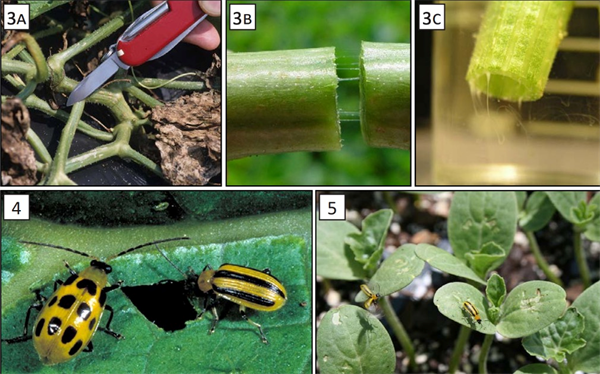

Bacterial wilt is caused by Erwinia tracheiphila; striped and spotted cucumber beetles (Fig 4 and 5) serve as vectors, carrying the bacterium from plant to plant during the growing season. The life cycles of the bacterial wilt organism and its vectors are closely associated, and bacterial wilt is directly correlated to striped and spotted cucumber beetle populations. These beetles hibernate through winter under leaf litter and in other protected sites; all the while, the bacterial wilt pathogen overwinters within the gut of the striped cucumber beetle. The beetles become active once temperatures remain above 55°F in spring. As soon as cucurbit seedlings begin to break through the ground, the beetles begin to feed on cotyledons and later feed on leaves, stems, and flowers. Striped cucumber beetle larvae also feed on root systems, causing damage that can result in wilt. The bacterial wilt organism is deposited through beetle mouthparts and the frass deposited onto/ into wounds created during beetle feeding. Once the bacterium invades a plant’s water conducting vessels (xylem), it spreads rapidly throughout the plant. The matrix of bacteria and ooze obstructs water movement in the xylem vessels, which causes wilt symptoms. Further spread of the pathogen occurs when beetles feed on diseased plants and then feed on nearby healthy plants. Close to harvest, a second generation of striped cucumber beetle may acquire the bacterium while feeding on infected plant tissues. Fall-planted cucurbits may be infected by this generation. These late-season adults will overwinter with the live bacterium in their gut and possibly transmit the pathogen to young plants the next spring. The bacterium cannot survive in infected plant debris from one season to the next.

Prevention of bacterial infections is dependent upon preventing cucumber beetle vectors from feeding on cucurbit plants. Early protection is critical for long-term disease management, which should begin as soon as seedlings emerge or when plants are transplanted into fields or gardens. Once it is evident that plants are infected, they should be removed from the site and destroyed. An early, aggressive management approach has been shown to reduce amounts of disease later in the season.

Start an insecticide program as soon as seedlings emerge or immediately after transplanting. This is critical to protecting very small plants from beetle feeding and, ultimately, from bacterial wilt. Bactericides are not recommended for management of bacterial wilt disease. Plastic and reflective mulches, crop rotation have shown promising effect against the insects.

More information: http://plantpathology.ca.uky.edu/

To contact Bindu Poudel go to:

bpoudel@email.arizona.edu