Apr 2, 2025

Tracking Cantaloupe (Melon) Crop Growth and Development

Being able to accurately track crop development and then to describe and predict important stages of crop growth and development (crop phenology) and harvest dates is important for improving melon (Cucumis melo ‘reticulatus’ L.) crop management (e.g. fertilization, irrigation, harvest scheduling, pest management activities, labor, and machinery management, etc.). It is best to monitor and predict plant development based on the actual thermal conditions in the plant’s environment. Thermal conditions are a more reliable measure and predictive tool for plant development as opposed to a calendar, simply because plant growth is a direct response to temperature and environmental conditions.

Various forms of temperature measurements and units commonly referred to as heat units (HU), growing degree units (GDU), or growing degree days (GDD) have been utilized in numerous studies to predict phenological events for many crop plants (Baskerville and Emin, 1969; Brown, 1989; Baker and Reddy, 2001; and Soto, 2012). A graphical depiction of HU computation using the single sine curve procedure is presented in Figure 1 (Brown, 1989).

Twenty-five years ago we began working on the development and annual testing of a phenology model for desert cantaloupe production for Arizona conditions. The basic cantaloupe phenology model is shown in Figure 2 (Silvertooth, 2003; Soto et al., 2006; and Soto, 2012). Since cantaloupes are a warm season crop, we use the 86/55 ºF thresholds for phenological tracking.

This melon crop phenology model was developed under fully irrigated and well-managed conditions. That is important since non-irrigated fields are more likely to experience water stress, which significantly disrupts crop development patterns.

Key stages of growth or “guideposts” indicated in Figure 2 represent general average or “target” values that are subject to a slight degree of natural variation, which is normal.

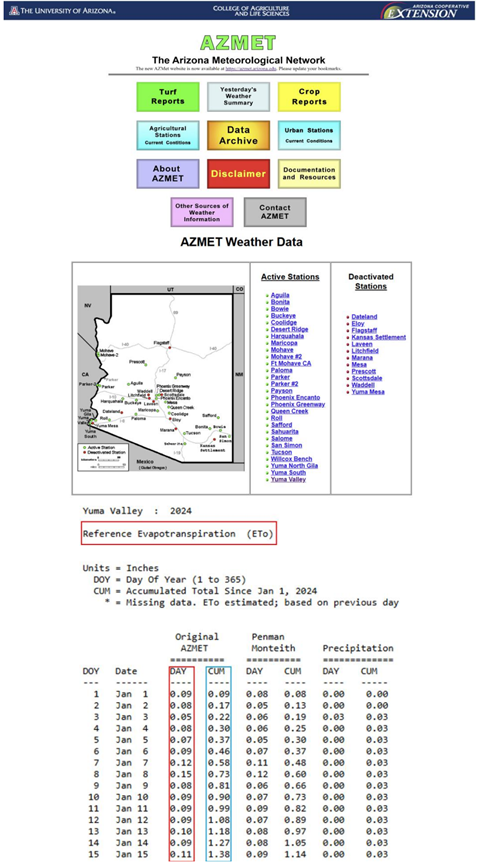

Referencing the data from the Arizona Meteorological Network (AZMET) and several locations in the Yuma area, the HU accumulations (86/55 ºF thresholds) from 1 January 2025 to a set off our possible 2025 planting dates are listed in Table 1. The HU accumulations from 1 January 2025 to 30 March 2025 are listed in Table 2.

The HU accumulations after planting (HUAP) for these four possible planting dates for three Yuma area locations to 30 March 2025 are shown in Table 3. The HUAP values in Table 3 are simply the difference between the values in Tables 1 and 2. An example for the Yuma Valley, 15 January 2025 planting date is: 718.7 HU - 73.1 HU = 645.6 ~ 646 HUAP.

It is rather easy to test and evaluate this crop phenology model in the field under various planting dates, varieties, and conditions. The information in Table 3 can help serve as a reference to check for melon crop development in the field against this phenological model in Figure 2.

For melon crops in the lower Colorado River Valley, we would currently expect to find fields planted and watered up in mid-January to have small melons approaching golf-ball size and fields planted in early March should be starting to show fresh blooms soon.

Table 1. Heat unit accumulations (86/55 ºF thresholds) after 1 January 2025 on four possible 2025 planting dates utilizing Arizona Meteorological Network (AZMET) data for each representative site.

Yuma Valley: https://azmet.arizona.edu/application-areas/heat-units/station-level-summaries/az02

Yuma North Gila: https://azmet.arizona.edu/application-areas/heat-units/station-level-summaries/az14

Roll: https://azmet.arizona.edu/application-areas/heat-units/station-level-summaries/az24

Table 2. Heat unit accumulations (86/55 ºF thresholds) after 1 January 2025 to 30 March 2025 utilizing Arizona Meteorological Network (AZMET) data for each representative site.

Table 3. Heat unit accumulations (86/55 ºF thresholds) after planting (HUAP) from four possible 2025 planting dates and three sites in the Yuma area utilizing Arizona Meteorological Network (AZMET) data for each representative site. Each value is rounded to the next whole number. Note: the values in Table 3 are determined by taking the difference between the HUs for each representative site and four planting dates in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Graphical depiction of heat unit computation using the single sine curve procedure. A sine curve is fit through the daily maximum and minimum temperatures to recreate the daily temperature cycle. The upper and lower temperature thresholds for growth and development are then super imposed on the figure. Mathematical integration is then used to measure the area bounded by the sine cure and the two temperature thresholds (grey area). (Brown, 1989)

Figure 2. Heat Units Accumulated After Planting (HUAP, 86/55 °F)