-

May 15, 2019Weeds Can Influence Insect Management

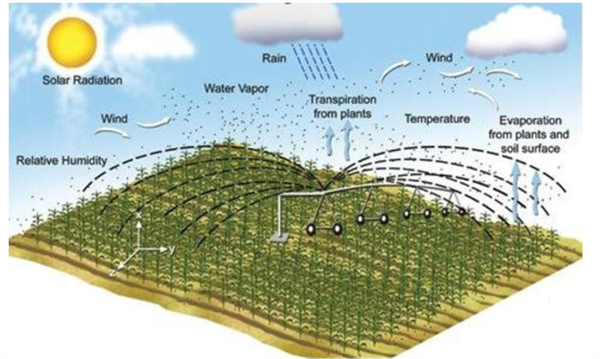

Effective weed management is critical for leafy vegetable and melon production in the desert southwest for all the obvious reasons. However, weed management is also essential for another important, but often overlooked, reason. Several common weed species can serve as host plants for many important insect pests, and when weeds are not controlled in the field they can be an impediment to insect control. Although weeds can serve a beneficial role by harboring insect natural enemies and pollinators, the consequences resulting from weeds harboring insect pests often outweigh benefits they potentially provide. Although flowering weeds can provide a reservoir for natural enemies, and a source of nectar and pollen for a pollinators, these same weedy refuges can serve as host sources for many key insect pests that cause economic damage to vegetable crops. Weeds found on field margins and ditch banks can provide insect pests with suitable resources needed for rapid population growth which subsequently can lead to insect infestations occurring in adjacent vegetable crops. In addition, many weed species can provide insects with host plants that serve as a bridge between cropping seasons when vegetables crops are not in production (May-August). Volunteer melons and cotton can also considered weeds (“a plant out of place”). If not controlled in a timely manner, these weedy volunteer plants can sustain large numbers of insect pests, as well as many of the plant viruses that are transmitted by insect vectors, that can migrate onto newly planted fields. Finally, weeds can serve as impediments to insecticide applications. Dense weed foliage in vegetable and melon fields can negatively influence foliar spray applications by intercepting spray droplets before reaching the target crop, which can result in less insecticide deposition and unacceptable crop damage. Soil applied insecticides (e.g., imidacloprid, Coragen, Verimark) can also be impacted by unmanaged weed growth. Weeds growing unchecked during stand establishment can compete with the seedling plants for water and fertilizer, but they can also compete with crop plants for soil insecticides. Excessive weed densities can significantly intercept insecticides in the soil profile and reduce the amount available for uptake by the target crop. For more information on this topic, please visit Weed Interference with Insect Management in Desert Crops.

To contact John Palumbo go to: jpalumbo@ag.Arizona.edu

To contact John Palumbo go to: jpalumbo@ag.Arizona.edu