-

Oct 4, 2023Sustaining Insecticide Efficacy……Rotation, rotation, rotation

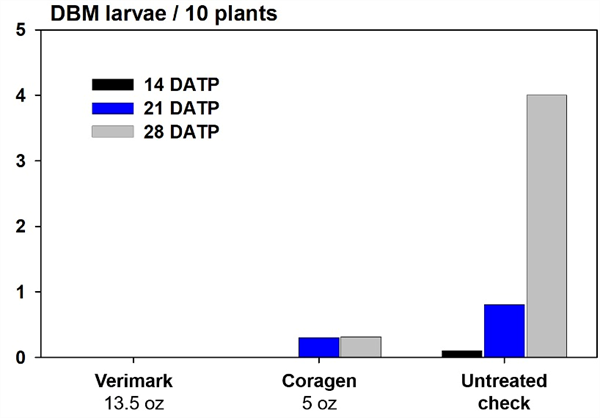

Even though temperatures and humidity has dropped, worm pressure remains steady in most growing areas. Here at the Ag Center, armyworm pressure is about average for early October, but still troublesome on new stands. Cabbage looper eggs and young larvae are now becoming abundant on all our crops, and PCAs are reporting an increase in looper pressure. Pheromone trap counts for armyworm and loopers remain below average in most areas. However, Diamondback moth larvae are unusually abundant on broccoli and transplants at the Ag Center. I’ve had several PCA reports of diamondback pressure in transplanted and direct seeded brassica crops in the Wellton and Tacna areas. Trap catches have begun to increase also. So far, all insecticide products we’ve tested are providing good DBM control and no complaints from the field. In one of my trials, the Verimark transplant tray drench treatment on cauliflower (Sep 5 wet date) was still active against DBM at 28 days following transplanting (see graph below).

Fortunately for local PCAs, several insecticide alternatives are available that provide excellent residual activity on these pests (see the Sept 20 update). Perhaps equally important, many of the products have unique modes of action (MOA) that can be alternated throughout the growing season. This is important because the most fundamental way to reduce the risk of insecticide resistance is to eliminate exposure of multiple generations of Leps to the same MOA. By using a different MOA on each subsequent spray application, you can minimize the risk of resistance by Lep larvae to these insecticide compounds. In contrast, repeatedly applying insecticide products with the same MOA for Lep control in the same area will significantly increase the risk of resistance. This is particularly important with the Diamide group of insecticides (IRAC group 28). These products can be applied as both foliar sprays and soil systemic treatments, and currently 7 Diamide products are for use labeled in leafy vegetables - all with the same MOA (Coragen, Durivo, Besiege, Minecto Pro, Verimark, Exirel and Harvanta). To avoid confusion among the Diamides, the IRAC group number (28) is placed on each label, adjacent to the product name. Furthermore, applying a Diamide product (i.e., Coragen/Verimark) to the soil at planting or as a tray drench, and then subsequently applying Diamide foliar sprays (i.e., Harvanta/Besiege) on the same field is not a good idea as it can expose multiple generations of Leps to the same MOA. For example, under ideal weather conditions, one could potentially expose 5-6 generations of BAW or DBM to the same MOA given the residual efficacy of the diamides. That’s not a good way to use these products if you want them to remain effective. Since the Diamides, as well as the other key products currently available (e.g., Radiant, Proclaim, Intrepid, Avaunt, Bts), are critical to effective management of Leps in leafy vegetables, PCAs should consciously avoid the overuse of any of these compounds. The most effective way to delay the onset of resistance by Leps in leafy vegetables is to consider the recommendations provided in the guidelines entitled Insecticide Resistance Management for Beet Armyworm, Cabbage Looper and Diamondback Moth in Desert Produce Crops.

To contact John Palumbo go to: jpalumbo@ag.Arizona.edu