When going into the field to evaluate a crop, there are typically three fundamental points we need to take into consideration that include: 1) stage of growth, 2) general crop vigor and yield potential, and 3) anticipate the next stage of development and what we need to do in terms of field crop management. These considerations are commonly focused on aboveground crop evaluations. The root system is also an important part of the crop condition to evaluate but we commonly do not evaluate roots because of the difficulty in doing so.

Root systems and early development were described in a basic manner in a recent article on 4 September (UA Vegetable IPM Newsletter Volume 15, No. 18).

The effective root zone depth is the depth of soil used by the bulk of the plant root system to explore a soil volume and obtain plant-available moisture and plant nutrients. Effective root depth is not the same as the maximum root zone depth. As a rule of thumb, we commonly consider that about 70% of the moisture and nutrient uptake by plant roots takes place in the top 24 inches of the root zone; about 20% from the third quarter; and about 10% from the soil in the deepest quarter of the root zone (Figure 1).

The small and very fine root hairs are the most physiologically active portion of a developing root system. It is important that plants continue to develop and generate fresh young roots and an abundance of fine root hairs to maintain water and nutrient uptake.

Figure 1. General pattern for plant-water and nutrient uptake from the soil profile.

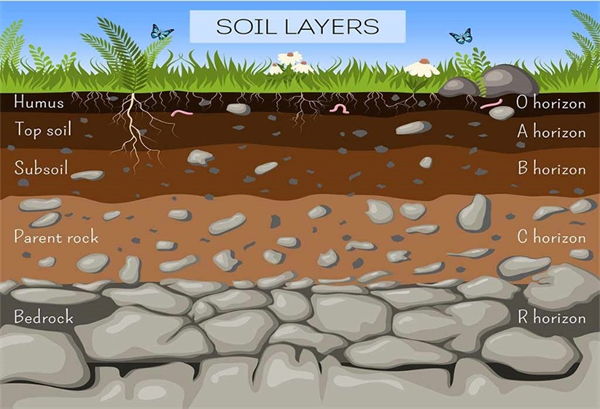

Root development patterns are dependent on the nature of the soil profile in the field. Soil profiles with compaction layers, as well as rock, clay, or caliche layers can limit and alter root development and the full exploration of the soil volume that the plants are capable of (Figure 2). So, it is good to know what the soil profile looks like in the field and understand how that will impact plant root development.

Figure 2. Generalized soil profile with major horizons.

Leafy green vegetable crops need to develop a marketable plant in a relatively short amount of time and a strong root system is essential. Transplants are commonly being used in vegetable crop production systems and the transition of transplants to field conditions is a major step in the production process. The transition is primarily experienced by the plant below ground.

Transplanted crops will have altered root systems due to the constraints within the rooting cone. Further root development beyond the original cone rooting mass is important for crop success. Thus, it is important to monitor the root system transition and the relationship to overall plant development.

Checking root systems is a plant destructive process since we need to literally excavate the roots from the soil and it does take time and effort. Accordingly, it is also important to be careful of where and how we sample plants and evaluate the root systems in a field.

Crop species can vary significantly in their patterns of root development, and it is important to know what is “normal” when evaluating crops in the field. An excellent reference for vegetable crop root system development is a 1927 publication by Dr. John E. Weaver and William E. Bruner from the University of Nebraska (Root Development of Vegetable Crops). This publication can be found at the following link:

https://soilandhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/01aglibrary/010137veg.roots/010137toc.html

A few basic examples from the Weaver and Bruner publication are provided in the following figures (Figures 3-10).

Figure 3. Cauliflower, 3 weeks after transplanting

Figure 4. Cabbage roots, 55 days after transplanting.

Figure 5. Cabbage roots, 75 days after transplanting.

Figure 6. Pepper roots, 24 days.

Figure 7. Pepper roots, 45 days (6 weeks).

Figure 8. Pepper roots, mature.

Figure 9. Lettuce roots, 3 weeks. The roots on the right were grown in compact

soil, the roots on the left were grown in loose/open soil.

Figure 10. Lettuce roots, 60 days.

At events and in the halls of the Yuma Agricultural Center, I’ve been hearing murmurings predicting a wet winter this year…

As the Yuma Sun reported last week, “The storms of Monday, Aug. 25 [2025], were the severest conditions of monsoon season so far this year in Yuma County, bringing record-rainfall, widespread power outages and--in the fields--disruptions in planting schedules.”

While the Climate Prediction Center of the National Weather Service maintains its prediction of below average rainfall this fall and winter as a whole, the NWS is saying this week will bring several chances of scattered storms.

These unusually wet conditions at germination can favor seedling disease development. Please be on the lookout for seedling disease in all crops as we begin the fall planting season. Most often the many fungal and oomycete pathogens that cause seedling disease strike before or soon after seedlings emerge, causing what we call damping-off. These common soilborne diseases can quickly kill germinating seeds and young plants and leave stands looking patchy or empty. Early symptoms include poor germination, water-soaked or severely discolored lesions near the soil line, and sudden seedling collapse followed by desiccation.

It is important to note that oomycete and fungal pathogens typically cannot be controlled by the same fungicidal mode of action. That is why an accurate diagnosis is critical before considering treatments with fungicides. If you suspect you have seedling diseases in your field, please submit samples to the Yuma Plant Health Clinic or schedule a field visit with me.

National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/

National Weather Service forecast: https://forecast.weather.govInterested in the latest automated weeding technologies? University of California Cooperative Extension will be hosting the 2024 Automated Technology Field Day where twelve of the newest commercial and academic thinning and weed control technologies will be demonstrated in the field. Featured technologies, some showcased for the first time to a general audience, include a high voltage electric weeder that kills weed seed pre-emergence, laser weeders (two types), “smart” precision spot sprayers (four types), “smart” in-row cultivators (four types), and the UA/UC Davis smart steam applicator for killing weed seed and soilborne pathogens pre-emergence. Company representatives and university personnel will be on hand to discuss their equipment. The event will be held from 9:00 am – 12:00 noon, Thursday, June 27th in Salinas, CA. For additional information, see the event flyer below.

The SW Ag Summit is taking place in Yuma this week. We will have the Weed Control breakout session on Thursday, 22 February 2024 at 1:30 pm in room AS 115 of the AWC campus. Here’s what are we going to cover:

Do you know what the IR-4 Project is?

Established in 1963 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and land-grant universities this project helps ensure that specialty crop farmers have legal access to safe and effective crop protection products and contributes to developing data necessary for the registration products for best pest management. Do we have this project in Yuma?

A Weed Scientist and Principal Biologist from IR-4 and NC State University will explain what this process of making more tools available to growers takes.

Additionally, we will have a representative from BASF chemical company who will present NEW WEED CONTROL TECHNOLOGIES as well as active ingredients developed by his company.

We all know with the loss of DCPA (Dacthal) herbicide our weed management tools were reduced. You asked the Veg IPM Team to look for ALTERNATIVES for Broccoli and Onion. We are doing some Trials at the UA Yuma Ag Center with products Such as Napropamide (Devrinol), which has the Devrinol DF XT dry formulation and the Devrinol 2-XT liquid.

Which one is more aggressive? How does water incorporation affect it? How good is it on goosefoot, lambsquarter, knotweed?

Other treatments we are looking at on broccoli are Goal Tender, Prefar, Prowl, Treflan, Enversa, Rinskor.

For direct seeded onion we are testing Prefar, Etothron SC, Dual, a combination of PREFAR+PROWL PREEMERGERGENCE at low rates, Outlook+Prowl.

We would like to share our observations if you honor us coming to our session. Again, it is TOMORROW Thursday, 22 February 2024 at the Arizona Western College AS 115 room. This session will start at 1:30 pm.

Get your free copy of the Weed Seedling Identification Pocket Guide at the Yuma Agricultural Center.

Biological control is one of the key tools for pest management in organic crop production. By maintaining permanent habitats and food sources for the pests’ natural enemies (good bugs) in the vicinity of your farms, you can ensure the continuous availability of the natural enemies. When the growing season starts, the good bugs will be readily available to attack the pests before they become established in the crops.

Researchers have found that planting a diversity of flowering plants (e.g., sweet alyssum, nasturtium, milkweeds, common cryptantha, hillside vervain, wild petunia, etc.) on a small portion of your farms or the farms’ border can provide adequate food and shelter allowing to maintain abundant and diverse natural enemy species, including syrphid flies, tachinid flies, lacewings, parasitic wasp, etc. that will attack aphids, thrips, lepidopterans, and more.

As you plan for the next season, please consider planting flowering plants on your farms’ borders or on dedicated patches to conserve natural enemies and enhance your biological control.

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches can be viewed here.

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts down in most over the last month, but increased activity in Wellton and Tacna in the past week; above average for this time of season.

Beet armyworm: Moth trap counts increased in most areas, above average for this time of the year.

Cabbage looper: Moths remain in all traps in the past 2 weeks, and average for this time of the season.

Diamondback moth: Adults decreased to all locations but still remain active in Wellton and the N. Yuma Valley. Overall, below average for January.

Whitefly: Adult movement remains low in all areas, consistent with previous years.

Thrips: Thrips adults movement decreased in past 2 weeks, overall activity below average for January.

Aphids: Winged aphids are still actively moving, but lower in most areas. About average for January.

Leafminers: Adult activity down in most locations, below average for this time of season.