There are more than 100 chemical elements known to man today. However, only 16 have been proven to be essential for plant growth. The essential elements for plant growth are in the upper portions of the periodic table with lower atomic numbers, indicating the lighter and more volatile elements that are in higher concentrations closer to the earth’s surface and part of the rocks that commonly serve as the parent materials for soils.

For a nutrient to be classified as essential, certain rigid criteria must be met. These criteria are as follows (Havlin, et al., 2014; Troeh and Thompson, 2005; Weil and Brady, 2017; Warren et al., 2017):

The essential elements and their chemical symbols are listed in Table 1. Three of the 16 essential elements – carbon, hydrogen and oxygen – are supplied mostly by air and water. These elements are used in relatively large amounts by plants and are non-mineral, often referred to as organic nutrients and they are supplied to plants by carbon dioxide and water.

The other 13 essential elements are mineral elements and must be supplied by the soil and/or fertilizers. Not all are required for all plants, but all have been found to be essential to some (Tisdale & Nelson).

Table 1. Essential plant nutrients, chemical symbols, and sources.

|

Mostly from air and water (non-mineral) |

Mostly from air and water (non-mineral) |

From soil and/or fertilizers (mineral) |

From soil and/or fertilizers (mineral) |

From soil and/or fertilizers (mineral) |

From soil and/or fertilizers (mineral) |

|

Element |

Symbol |

Element |

Symbol |

Element |

Symbol |

|

Carbon |

C |

Nitrogen |

N |

Iron |

Fe |

|

Hydrogen |

H |

Phosphorus |

P |

Manganese |

Mn |

|

Oxygen |

O |

Potassuim |

K |

Zinc |

Zn |

|

|

|

Calcium |

Ca |

Copper |

Cu |

|

|

|

Magnesium Mg |

Mg |

Boron |

B |

|

|

|

Sulfur |

S |

Molybdenum |

Mo |

|

|

|

|

|

Cholorine |

Cl |

The essential plant nutrients may be grouped into three categories. They are as follows:

At events and in the halls of the Yuma Agricultural Center, I’ve been hearing murmurings predicting a wet winter this year…

As the Yuma Sun reported last week, “The storms of Monday, Aug. 25 [2025], were the severest conditions of monsoon season so far this year in Yuma County, bringing record-rainfall, widespread power outages and--in the fields--disruptions in planting schedules.”

While the Climate Prediction Center of the National Weather Service maintains its prediction of below average rainfall this fall and winter as a whole, the NWS is saying this week will bring several chances of scattered storms.

These unusually wet conditions at germination can favor seedling disease development. Please be on the lookout for seedling disease in all crops as we begin the fall planting season. Most often the many fungal and oomycete pathogens that cause seedling disease strike before or soon after seedlings emerge, causing what we call damping-off. These common soilborne diseases can quickly kill germinating seeds and young plants and leave stands looking patchy or empty. Early symptoms include poor germination, water-soaked or severely discolored lesions near the soil line, and sudden seedling collapse followed by desiccation.

It is important to note that oomycete and fungal pathogens typically cannot be controlled by the same fungicidal mode of action. That is why an accurate diagnosis is critical before considering treatments with fungicides. If you suspect you have seedling diseases in your field, please submit samples to the Yuma Plant Health Clinic or schedule a field visit with me.

National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/

National Weather Service forecast: https://forecast.weather.govAs part of their efforts to promote agtech, Western Growers is developing a freely available image library of key specialty crops. The idea is to create a database of labeled/annotated images that startups and researchers can use as training sets to develop AI software for automated/robotic machines. Sets of images of mature iceberg, romaine, broccoli, cauliflower and strawberry crops have been completed and are available at https://github.com/AxisAg/GHAIDatasets/tree/main/datasets. These images are useful for creating AI models for automated harvesting machines.

Last season, in collaboration with Axis Ag, Inc., we worked to expand the database to include images of crops at all growth stages. This will allow users to develop AI tools for crop thinning, weeding and crop health monitoring. Francisco Calixtro, a UofA Yuma student majoring in Ag Systems Management, spent the winter collecting images of various vegetable crops throughout their growth cycle using an Amiga1 (farm-ng, Watsonville, CA) robot equipped with a camera. These images will be sorted, labeled and uploaded to the image library. We’ll announce when these data sets become available.

Special thank you to Jason Mellow, Axis Ag, Inc. and to the many growers who allowed us to capture images of their fields.

Fig. 1. Francisco Calixtro, UofA Yuma student, operates an Amiga1 (farm-ng,

Watsonville, CA) robot equipped with a camera to capture images of various

vegetable crops at different growth stages. Images will be labeled and

uploaded to a freely available image library to facilitate development of AI

software for automated/robotic machines. (Photo credits: Jason Mellow and

Francisco Calixtro)

[1] Reference to a product or company is for specific information only and does not endorse or recommend that product or company to the exclusion of others that may be suitable.

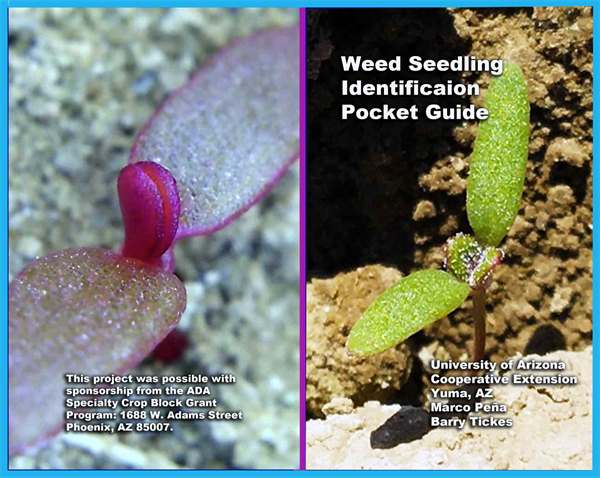

In our last newsletter we talked about the importance of proper weed identification before making decisions on control measures. We mentioned some of the literature that the Vegetable IPM Team uses at the Yuma Agricultural Center.

An increasing number of PCAs and growers are using several phone applications for weed ID.

In this update I would like to share some data that was collected from a group of students of the 2024 PLS 300 Applied Weed Science class.

Professor Barry Tickes asked his students to download two phone applications and test the accuracy of the weed species ID. The recommended applications used were PlantNet and PictureThis Plant Identifier, which according to some Pest Control Advisors are reasonably accurate.

We provided a display of 9 weeds to the students to take images and upload to the phone apps for ID and here are the results obtained:

Weed PictureThis PlantNet

Annual bluegrass 6 0

Creeping woodsorrel 8 6

Nettleleaf goosefoot 4 3

Prickly lettuce 8 0

Spiny sowthistle 6 1

Spinach 8 6

Malva 6 1

Silversheath knotweed 5 0

Littleseed canarygrass 0 0

PictureThis Plant Identifier performed better than PlantNet in this evaluation. Interestingly in 2022 the weed science class evaluated PlantNet with results showing that 84.6 % of the time the application was correct. If you have another application that you recommend, please send it in your comments and we will share it with others in this newsletter.

Get your free copy of the Weed Seedling Identification Pocket Guide at the Yuma Agricultural Center.

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches can be viewed here.

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts down in most over the last month, but increased activity in Wellton and Tacna in the past week; above average for this time of season.

Beet armyworm: Moth trap counts increased in most areas, above average for this time of the year.

Cabbage looper: Moths remain in all traps in the past 2 weeks, and average for this time of the season.

Diamondback moth: Adults decreased to all locations but still remain active in Wellton and the N. Yuma Valley. Overall, below average for January.

Whitefly: Adult movement remains low in all areas, consistent with previous years.

Thrips: Thrips adults movement decreased in past 2 weeks, overall activity below average for January.

Aphids: Winged aphids are still actively moving, but lower in most areas. About average for January.

Leafminers: Adult activity down in most locations, below average for this time of season.