Soils with excess soluble salts, saline soils, and/or excess sodium (Na+) concentrations (sodic) are a natural feature of desert soils and common in arid land agriculture. This is primarily due to an accumulation of soluble salts near the soil surface as water evaporates from the soil surface.

Saline soils are a problem in crop production systems because of the sensitivity to salinity of crop plants, although plants vary in their degree of sensitivity. The period of greatest plant sensitivity to salinity is in the early stages of development, during germination and stand establishment.

Sodic soils are a problem in crop production systems because of the adverse effects of excess sodium on soil structure, causing a dispersion of soil particles and the breakdown of soil aggregates. This leads to poor water infiltration and percolation in the soil profile.

Some basic points associated with saline and/or sodic soils and management are outlined in the following sections.

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/PA_NRCSConsumption/download/?cid=nrcseprd589210&ext=pdf

Sodic soil reclamation does require an amendment that will facilitate the chemical exchange of Na+, usually from a calcium (Ca2+) source, such as gypsum (CaSO4).

An effective and straightforward method of calculating a leaching requirement (LR) can be calculated with the following equation that was presented by the USDA Salinity Laboratory (Ayers and Westcot, 1989).

Leaching Requirement (LR) Calculation:

Where:

ECw = salinity of the irrigation water, electrical conductivity (dS/m)

ECe = critical plant salinity tolerance, electrical conductivity (dS/m)

i.Drip irrigation systems are commonly very limited in this respect.

i.Examples: wheat, alfalfa, sudangrass, etc.

Hi, I’m Chris, and I’m thrilled to be stepping into the role of extension associate for plant pathology through The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension in Yuma County. I recently earned my Ph.D. in plant pathology from Purdue University in Indiana where my research focused on soybean seedling disease caused by Fusarium and Pythium. There, I discovered and characterized some of the first genetic resources available for improving innate host resistance and genetic control to two major pathogens causing this disease in soybean across the Midwest.

I was originally born and raised in Phoenix, so coming back to Arizona and getting the chance to apply my education while helping the community I was shaped by is a dream come true. I have a passion for plant disease research, especially when it comes to exploring how plant-pathogen interactions and genetics can be used to develop practical, empirically based disease control strategies. Let’s face it, fungicide resistance continues to emerge, yesterday’s resistant varieties grow more vulnerable every season, and the battle against plant pathogens in our fields is ongoing. But I firmly believe that when the enemy evolves, so can we.

To that end I am proud to be establishing my research program in Yuma where I will remain dedicated to improving the agricultural community’s disease management options and tackling crop health challenges. I am based out of the Yuma Agricultural Center and will continue to run the plant health diagnostic clinic located there.

Please drop off or send disease samples for diagnosis to:

Yuma Plant Health Clinic

6425 W 8th Street

Yuma, AZ 85364

If you are shipping samples, please remember to include the USDA APHIS permit for moving plant samples.

You can contact me at:

Email: cdetranaltes@arizona.edu

Cell: 602-689-7328

Office: 928-782-5879

Interested in staying up to date on the latest robotic ag technologies? The International Forum for Agricultural Robotics, FIRA, hosts two annual conferences focusing on robotics and autonomous farming solutions, one in Europe and one in the USA. They recently uploaded recordings of sessions from the 2024 World FIRA, held in Toulouse, France to YouTube. The site also contains playlists of themed breakout sessions from previous European and USA events (over 400 videos total). Highlights include panel discussions with growers and company executives, robot demos, and inno’pitches from startup companies. Most of the content, particularly from the USA events, is high quality and worth viewing.

Check it out by clicking here or on the image below.

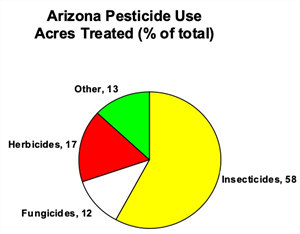

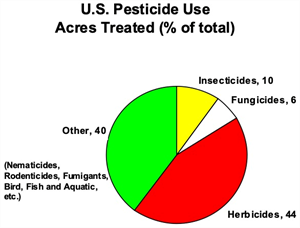

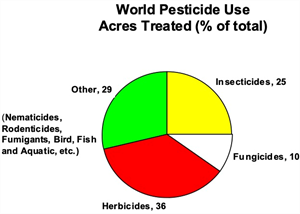

There are many different types of pests that affect crops grown in Arizona. The three types of pests most often cited as the source of most problems are insects, diseases and weeds. These are the same types of pests that are cited as causing the major agricultural pest problems across the U.S. and worldwide. Graphs 1-3 illustrate, however, that the relative importance of these types of pest problems differ in Arizona from the rest of the U.S. and worldwide. In terms of pesticide use, worldwide herbicides accounted for 36% of total usage, insecticides 25%, and fungicides 10% and other 29% (nematicides, rodenticides, fumigants, bird, fish and aquatic pests). In the U.S., herbicides accounted for 44%, insecticides 10%, fungicides 6%, and other 40% of pesticide use. In Arizona, however, insecticides accounted for 58%, herbicides 17% and fungicides 12%. This is only an indirect measure of the relative importance of these three areas of pest management and may be heavily influenced by the amount of pesticides used. For instance, it is common to spray for insects five or more times per season while it is uncommon to spray for weeds more than twice. None the less, these graphs illustrate that weeds are the predominant pest problem in agricultural areas across the U.S. and worldwide.

We wanted to share the information above obtained from the PCA Study Guide Section VI prepared by our "amigo" Barry Tickes who is teaching the Applied Weed Science Class at the University of Arizona this semester.

This time of year, John would often highlight Lepidopteran pests in the field and remind us of the importance of rotating insecticide modes of action. With worm pressure present in local crops, it’s a good time to revisit resistance management practices and ensure we’re protecting the effectiveness of these tools for seasons to come. For detailed guidelines, see Insecticide Resistance Management for Beet Armyworm, Cabbage Looper, and Diamondback Moth in Desert Produce Crops .

VegIPM Update Vol. 16, Num. 20

Oct. 1, 2025

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches below!!

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts declined across all traps from last collection; average for this time of year.

Beet armyworm: BAW moth increased over the last two weeks; below average for this early produce season.

Cabbage looper: Cabbage looper counts increased in the last two collections; below average for mid-late September.

Diamondback moth: a few DBM moths were caught in the traps; consistent with previous years.

Whitefly: Adult movement decreased in most locations over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.

Thrips: Thrips adult activity increased over the last two collections, typical for late September.

Aphids: Aphid movement absent so far; anticipate activity to pick up when winds begin blowing from N-NW.

Leafminers: Adult activity increased over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.