Oct 1, 2025

Developments in Plant Genetics

During the past 50-60 years, there have been some tremendous technological developments that have provided valuable tools enabling significant improvements in crop yields, quality, and production efficiencies. Some of the greatest of these developments have been in plant genetics.

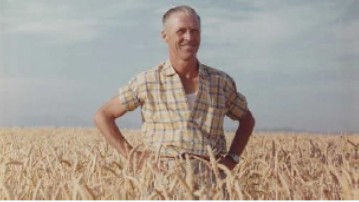

In 1970, Dr. Norman Borlaug (Figure 1) received the Nobel Peace Prize for his work with CIMMYT (Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo, or the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center) based in Ciudad Obregon, Sonora, Mexico. Borlaug and his CIMMYT colleagues were credited with the “Green Revolution” which was estimated to have saved at least 1B lives from starvation. Borlaug is the only agronomist to have received a Nobel Peace Prize.

Figure 1. Dr. Norman Borlaug, ca. 1963, Yaqui Valley, Sonora, Mexico.

Borlaug and his team accomplished two basic developments. First, using classical plant breeding methods, they bred dwarf wheat varieties that had a higher harvest index (a higher proportion of the total dry matter yield in the grain versus the vegetative parts of the plant). Second, they developed wheat varieties that were resistant to rust diseases, which had been devastating Mexican wheat crops for several decades. This CIMMYT program began in 1944 when Mexico was importing large amounts of wheat to support the population. Due to the success of this program, Mexico became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.

Borlaug and his colleagues transferred these new wheat varieties to southern Asia and between 1965 to 1970 wheat yields nearly doubled in Pakistan and India, greatly improving food security. These methods have been applied to other crops and other regions with great success (Borlaug, 2002).

In 1996 the first transgenic technologies were introduced in cotton and corn Bt varieties and utilized in crop production systems in the United States as result of molecular breeding programs. This incredible technology involved the insertion of genes from a common soil bacterium, Bacillus thuringiensis. These genes encode the production of insecticidal proteins, and thus, genetically transformed plants produce one or more toxins as they grow. The genes that have been inserted into these varieties produce toxins that are limited in activity almost exclusively to caterpillar pests (Lepidoptera family).

In the leafy green vegetable industry, new lettuce varieties have been developed over the past 40 years that offer the capacity for what is naturally a cool-season plant to be planted in the lower Colorado River Valley in August and September with average daily high temperatures of greater than 100°F. These are truly amazing developments from plant breeding programs.

The improved understanding in cellular-molecular biology and the details of DNA has led to new levels of capacity in crop improvement. This has led to the creation of molecular-markers, which are used in genomic-assisted plant breeding programs to identify genes linked to desired traits.

High-throughput phenotyping has provided the ability for plant geneticists to accurately identify and measure genetic traits. This provides the valuable capability of supplementing genomic information for precision breeding.

It is good to recognize and celebrate positive developments and achievements. Yet it is also important to recognize some major mistakes that have occurred in genetics and plant breeding.

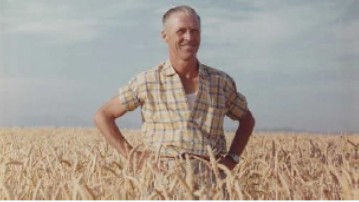

In the early 20th century, a Russian agronomist Trofim Lysenko (Figure 2) was a proponent of Lamarckism, which rejected Mendelian genetics in favor of his own idiosyncratic, pseudoscientific ideas later referred to as Lysenkoism (Cashari and Marshak, 1965).

Lysenko became Director of the Russian Institute of Genetics of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in 1940. He used his political influence and power to suppress dissenting opinions and discredit, marginalize, and imprison his critics, elevating his anti-Mendelian theories to state-sanctioned doctrine, which was supported by Josef Stalin, the General Secretary of the Communist Party and dictator of the Soviet Union. Lysenko not only rejected Mendelian genetics but encouraged farmers to plant very high populations based on his belief in the “law of the life of species”, believing that plants from the same “class” will not compete for resources. That of course was a faulty line of thinking without foundation, and it created disastrous consequences.

Lysenko's ideas and practices in plant breeding and crop production practices contributed to the famines that killed millions of people in the Soviet Union. In addition, the adoption of his methods beginning in 1958 in the People's Republic of China had similarly disastrous results, contributing to the Great Chinese Famine of 1959 to 1961. Stalin favored people like Lysenko who was from a peasant family and was lacking in formal education and academic training and with no affiliations to the academic community. Despite Lysenko’s destructive record, he was promoted and awarded the Medal of Lenin eight times.

As a result of Lysenko’s unorthodox ideas and Stalin’s support of him, Soviet scientists who refused to renounce genetics were dismissed from their posts and left destitute. Many notable Russian scientists were imprisoned.

After tremendous amounts of human suffering due to Lysenko’s influence with the resultant crop failures and the death of Stalin in 1953, Lysenko began to lose favor in the Soviet Union. In 1965 he was finally removed from his position as the Director of the Institute of Genetics at the Academy of Sciences in the Soviet Union after the removal of Nikita Khrushchev as the first secretary of the Communist Party and Premier of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev in 1964. Lysenko was ultimately disgraced in the late 1960s, but he did a lot of damage in 25 years.

Figure 2. Trofim Denesovich Lysenko, 1938.

The continued progress and genetic developments like those we have experienced in the past 60 years are not automatic and have required consistent and committed support in development of our basic understanding of plant genetics and biochemistry and the incorporation of that knowledge into well-directed plant breeding programs. Continued support and development basic science is essential for us to develop new tools with appropriate field applications.

We have many challenges in agriculture, and we need the benefit of good science and its application into our crop production systems to meet the needs of today and the future. We cannot afford a venture and descent into some form of Lysenkoism.

References:

Borlaug,N. E. 2002. "The green revolution revisited and the road ahead".Stockholm, Sweden. Nobelprize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/borlaug-lecture.pdf

Caspari,E. W.; Marshak, R. E. 1965. "The Rise and Fall of Lysenko". Science.149 (3681): 275–278. Bibcode:1965Sci... 149..275C.doi:10.1126/science.149.3681.275. PMID 17838094

To view this article as a PDF, click here and hit download.

To contact John Palumbo go to: jpalumbo@ag.Arizona.edu

To contact John Palumbo go to: jpalumbo@ag.Arizona.edu