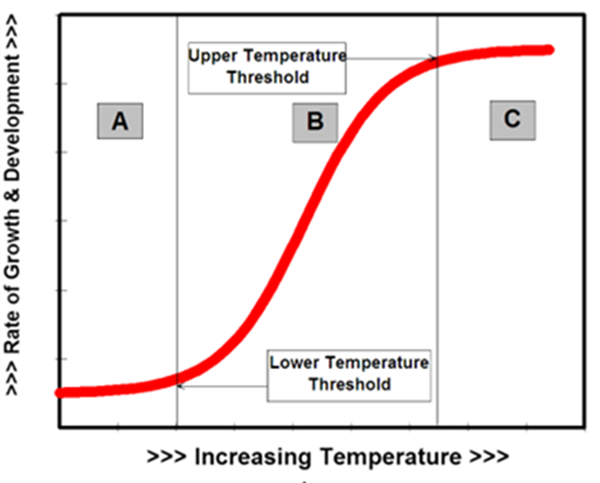

Water and nutrient demands coincide with the fruiting cycle of most crop plants. The efficient management of irrigation water and plant nutrients is enhanced by tracking crop development in the field and making decisions on plant demand and condtion. The use of heat units (HUs) with 86/55 oF upper and lower thresholds can be applied to warm season crops in the desert Southwest in relation to the thermal environmental impacts on the development of all crop systems (Brown, 1989), including chiles, (Figures 1 and 2).

Crop Phenology Relationship to Water and Nitrogen Demand

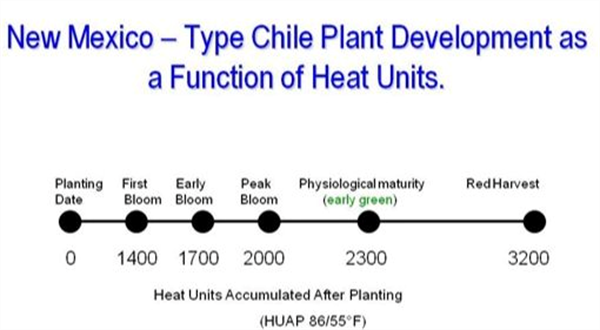

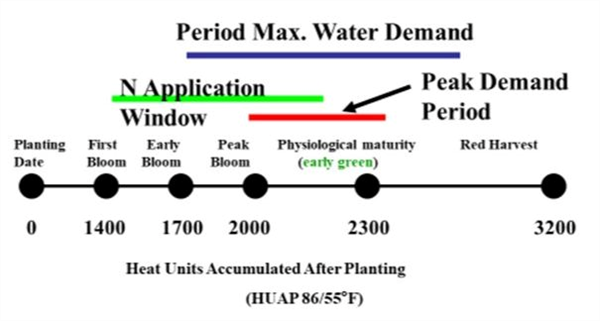

Phenological guidelines have been developed for many crops, including New Mexico (NM) type chiles (Soto-Ortiz and Silvertooth, 2007 and Silvertooth, et al, 2010; Figure 1). This phenological guideline can be used to identify or predict important stages of crop development that impact physiological requirements. For example, a phenological guideline can help identify stages of growth in relation to crop water use (consumptive use) and nutrient uptake patterns (Figure 3).

This information allows growers to improve the timing of water and N inputs to improve production efficiency. For most crops HU based phenological guidelines can be used to project critical dates such as harvest or crop termination. Many other inputs and applications related to crop management (e.g., pest management) can be derived from a better understanding of crop growth and development patterns.

Arizona chile production, consisting of NM type chile varieties, is mostly located in Cochise County in southeastern Arizona. The 2025 Arizona chile crop has been progressing steadily in line with the basic phenological model shown in Figure 2. For a set of fields near Pearce, Arizona with several different NM type varieties and planting dates ranging from 2 – 22 April 2025, current heat unit accumulations after planting are 1,785 – 1,957 (Figure 4a-d). The crop is moving into peak bloom and the period of peak N and water demand.

This is very good time in the season to evaluate these fields in relation to current irrigation and N fertilization needs.

Figure 1. Typical relationship between the rate of plant growth and development and

temperature. Growth and development ceases when temperatures decline below the

lower temperature threshold (A) or increase above the upper temperature threshold (C).

Growth and development increases rapidly when temperatures fall between the lower

and upper temperature thresholds (B).

Figure 2. Basic phenological guideline for irrigated New Mexico-type chiles.

Figure 3. Basic phenological guideline for irrigated New Mexico-type chiles with periods

of peak water and nutrient demand, including optimum N application window.

Figure 4a. New Mexico type chile, variety Carne Duro, 31 July 2025.

Figure 4b. Crown set chiles, Carne Duro variety, 31 July 2025.

Figure 4c. Early fruit set, Carne Duro variety, 31 July 2025.

Figure 4d. Mid-canopy fruit set, Carne Duro variety, 31 July 2025.

References

Brown, P. W. 1989. Heat units. Bull. 8915, Univ. of Arizona Cooperative Extension,

College of Ag., Tucson, AZ.

Silvertooth, J.C., P.W. Brown, and S. Walker. 2010.Crop Growth and Development for

Irrigated Chile (Capsicum annuum). University of Arizona Cooperative Extension

Bulletin No. AZ 1529

Soto-Ortiz, R. and J.C. Silvertooth. 2007. A Crop Phenology Model for Irrigated New

Mexico Chile (Capsicum annuum L.) The 2007 Vegetable Report. Jan 08:104-122.

I hope you are frolicking in the fields of wildflowers picking the prettiest bugs.

I was scheduled to interview for plant pathologist position at Yuma on October 18, 2019. Few weeks before that date, I emailed Dr. Palumbo asking about the agriculture system in Yuma and what will be expected of me. He sent me every information that one can think of, which at the time I thought oh how nice!

When I started the position here and saw how much he does and how much busy he stays, I was eternally grateful of the time he took to provide me all the information, especially to someone he did not know at all.

Fast forward to first month at my job someone told me that the community wants me to be the Palumbo of Plant Pathology and I remember thinking what a big thing to ask..

He was my next-door mentor, and I would stop by with questions all the time especially after passing of my predecessor Dr. Matheron. Dr. Palumbo was always there to answer any question, gave me that little boost I needed, a little courage to write that email I needed to write, a rigid answer to stand my ground if needed. And not to mention the plant diagnosis. When the submitted samples did not look like a pathogen, taking samples to his office where he would look for insects with his little handheld lenses was one of my favorite times.

I also got to work with him in couple of projects, and he would tell me “call me John”. Uhh no, that was never going to happen.. until my last interaction with him, I would fluster when I talked to him, I would get nervous to have one of my idols listening to ME? Most times, I would forget what I was going to ask but at the same time be incredibly flabbergasted by the fact that I get to work next to this legend of a man, and get his opinions about pest management. Though I really did not like giving talks after him, as honestly, I would have nothing to offer after he has talked. Every time he waved at me in a meeting, I would blush and keep smiling for minutes, and I always knew I will forever be a fangirl..

Until we meet again.

For those interested in in-row weed control, checkout the quality video below (Fig. 1) on how finger weeders (Fig. 2) are being used on a 3,600 acre organic cotton farm in Texas. The grower states that finger weeders help him achieve 95-97% weed control and are a highly cost-effective tool for lowering hand weeding costs.

Fig. 1. Carl Pepper discusses how finger weeders are used to control in-row weeds on

his 3,600 acre organic cotton farm. Click here or on image to view. (Photo credit: Tilmor

LLC, Dalton, OH)

Fig. 2. Finger weeders, an in-row weeding tool, operating in seedling cotton. Finger

weeder pairs are centered on the seed row and overlapped slightly to loosen soil in the

row and uproot small weeds.

Dr. John Palumbo never sought the spotlight, but everything he did—every trial, field visit, and conversation—pointed us toward something better: better science, better decisions, better farming.

I’ve looked up to John since my undergraduate days. He was the model of what I hoped to become: a scientist grounded in integrity, driven by purpose, and deeply connected to the people and land he served. A career-long dream came true when I asked him to join my Ph.D. committee—and he said yes. A defining moment in my journey that I’ll always carry with me.

The work we hoped to do with him is now a reminder of how much he still had to offer. But more than anything, I’m grateful. Grateful that I got to learn from him, talk with him, and be challenged by him. I especially loved when I’d share an idea and he would provide feedback like, “Now I don’t like the sound of that, and I’ll tell you why...” To me that meant he was listening closely. He cared. He was genuine.

John didn’t just give us answers—he gave us perspective and the confidence to ask better questions. His perspective came from a place of hard-earned wisdom which he shared humbly and freely. We’ve lost a giant, but his impact remains in our work, our conversations, and the values he quietly instilled. His presence is deeply missed—and deeply lasting.As the desert vegetable season ramps up, organic growers face tough pest management challenges with limited insecticide options. To help address this, University of Arizona researchers at the Yuma Agricultural Center conducted field trials during the 2024–2025 season, testing OMRI-listed products on six key pests in leafy greens and Brassicas.

This article highlights results for products like Entrust, Pyganic, XenTari, and M-Pede, evaluated for their performance against diamondback moth, beet armyworm, whiteflies, green peach aphid, pale striped flea beetle, and western flower thrips. The results can help growers fine-tune their spray programs and make more informed decisions this season.

Click here to read the full report: Organic-Allowed Insecticide Options for the Management of Six Major Insect Pests in Arizona’s Vegetable CropsAs lettuce season approaches, irrigation management becomes critical for maintaining optimal soil moisture levels in the active root zone. Proper irrigation not only supports healthy crop growth but also prevents excessive water applications that can lead to nitrate leaching, an issue of both environmental concern and economic loss. Likewise, under-irrigation can reduce nitrogen uptake, as adequate soil moisture is essential for root absorption. This is especially critical in an extremely dry region like Yuma, where maintaining optimal soil moisture directly impacts both water and nitrogen use efficiency. This article provides an in-depth guide for growers on how to schedule irrigation based on crop growth stage, system type, and current weather conditions. The article introduces updated crop coefficient (Kc) values developed specifically for Yuma lettuce production through recent field research led by Drs. Sanchez and French, in partnership with Yuma Center of Excellence for Desert Agriculture (YCEDA). It also explains how to use the Arizona Meteorological Network(AZMET) and other practical evapotranspiration tools to make irrigation decisions more precise and site-specific.

Combining updated Kc values, local reference ET data, and irrigation efficiency concepts, this resource empowers growers to improve water use efficiency and sustain high yields and enhance different cropping systems in the region.

Click this link to read the full article: Estimating Crop Evapotranspiration Using Lettuce Crop Coefficients for Irrigation Scheduling in Yuma, Arizona.