When we go to the field to evaluate a crop, there are typically three fundamental points we need to take into consideration that include: 1) stage of growth, 2) general crop vigor and yield potential, and 3) anticipate the next stage of development and what we need to do in terms of field crop management. These considerations are commonly focused on aboveground crop evaluations. However, the root system is also an extremely important part of the crop condition to evaluate.

Root systems were described in a basic manner in a recent article on 2 May 2023 (UA Vegetable IPM Newsletter Volume 14, No. 9).

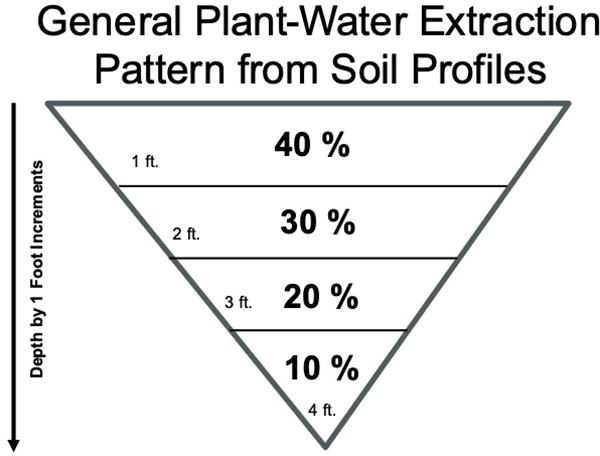

The effective root zone depth is the depth of soil used by the bulk of the plant root system to explore a soil volume and obtain plant-available moisture and plant nutrients. Effective root depth is not the same as the maximum root zone depth. As a rule of thumb, we commonly consider about 70% of the moisture and nutrient uptake by plant roots takes place in the top 24 inches of the root zone; about 20% from the third quarter; and about 10% from the soil in the deepest quarter of the root zone (Figure 1).

The small and very fine root hairs are the most physiologically active portion of a developing root system. It is important that the plants continue to develop and generate fresh young roots and an abundance of fine root hairs to maintain water and nutrient uptake.

Figure 1. General pattern for plant-water and nutrient uptake from the soil profile.

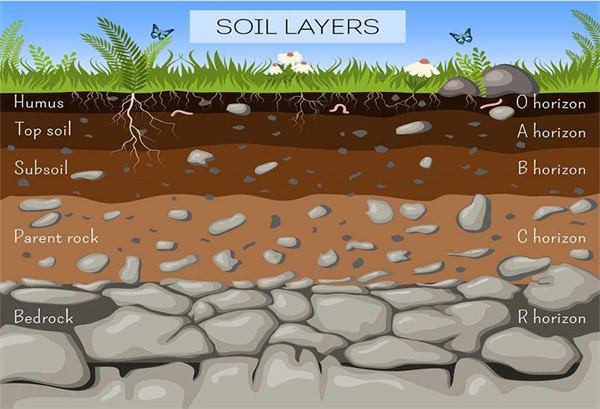

It is important to point out that these general root development patterns are dependent on the nature of the soil profile in the fields. Soil profiles with compaction layers, as well as rock or caliche layers will limit root development and full exploration of the soil volume that the plants are capable of (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Generalized soil profile with major horizons.

Therefore, in scouting fields and making crop evaluations, examining the root systems is an important part of the process. Leafy green vegetable crops need to develop a marketable plant in a relatively short amount of time and a strong root system is essential.

It does take more time and effort to check root systems and it is a plant destructive process since we need to literally excavate the roots. So, it is also important to be careful of where and how we sample plants and the root systems in a field.

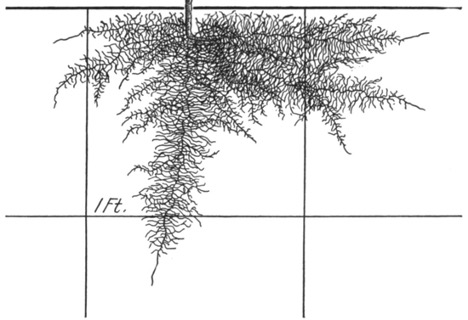

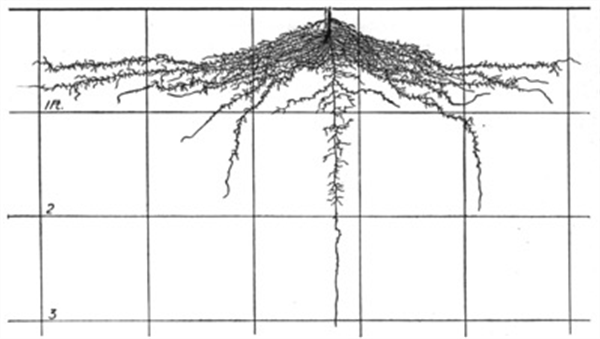

Crop species can vary significantly in their patterns of root development and it is important to know what is “normal” when evaluating crops in the field. An excellent reference for vegetable crop root system development is a 1927 publication by Dr. John E. Weaver and William E. Bruner from the University of Nebraska (Root Development of Vegetable Crops). This publication can be found at the following link:

https://soilandhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/01aglibrary/010137veg.roots/010137toc.html

A few basic examples from the Weaver and Bruner publication are provided in the following figures (Figures 3-10).

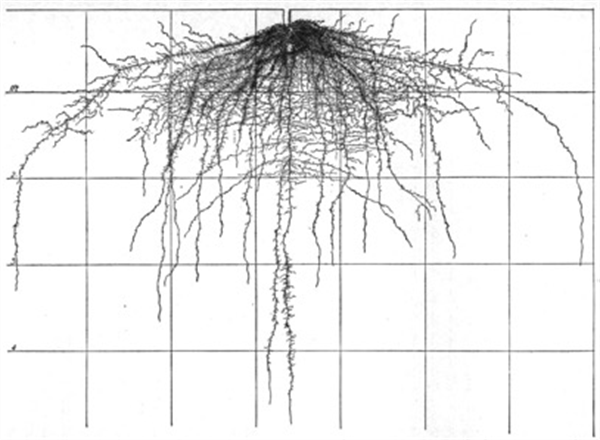

Figure 3. Cauliflower, 3 weeks after transplanting.

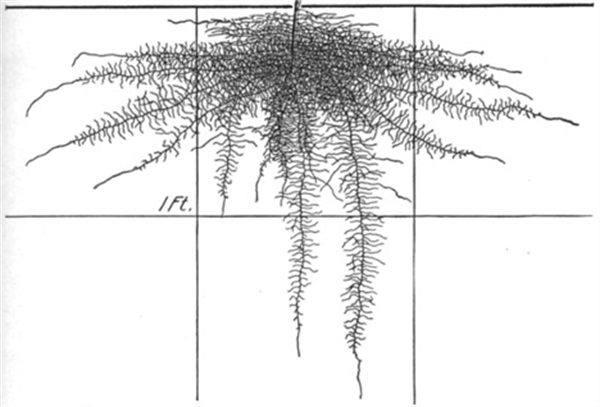

Figure 4. Cabbage roots, 55 days after transplanting.

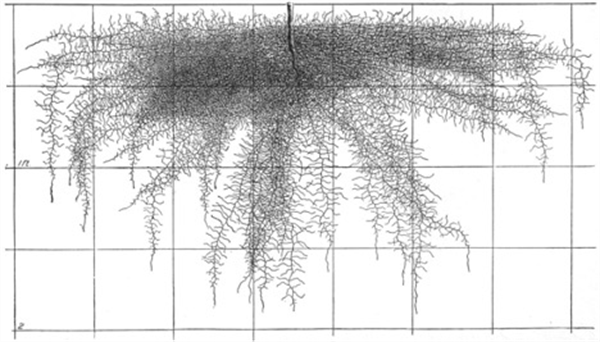

Figure 5. Cabbage roots, 75 days after transplanting.

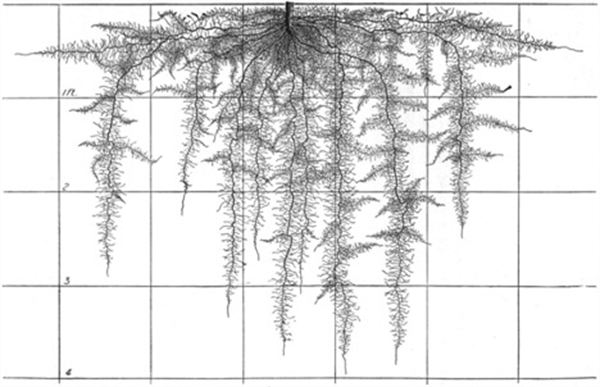

Figure 6. Pepper roots, 24 days.

Figure 7. Pepper roots, 45 days (6 weeks).

Figure 8. Pepper roots, mature.

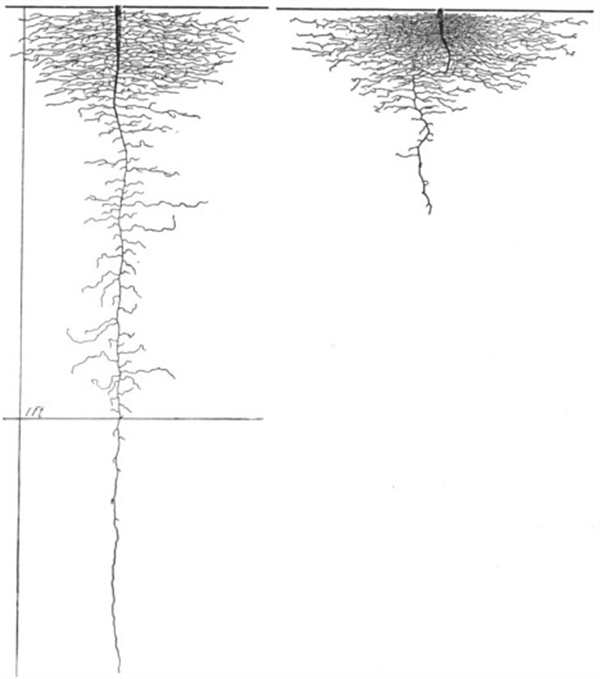

Figure 9. Lettuce roots, 3 weeks. The roots on the right were grown in compact soil, the roots on the

left were grown in loose/open soil.

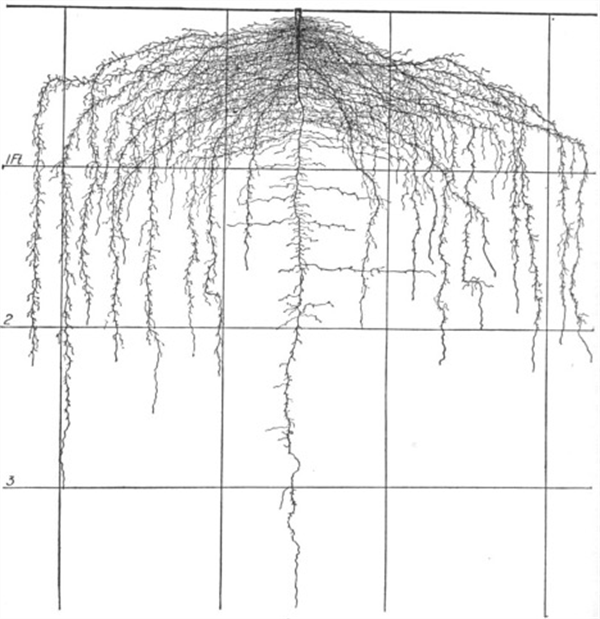

Figure 10. Lettuce roots, 60 days.

Hi, I’m Chris, and I’m thrilled to be stepping into the role of extension associate for plant pathology through The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension in Yuma County. I recently earned my Ph.D. in plant pathology from Purdue University in Indiana where my research focused on soybean seedling disease caused by Fusarium and Pythium. There, I discovered and characterized some of the first genetic resources available for improving innate host resistance and genetic control to two major pathogens causing this disease in soybean across the Midwest.

I was originally born and raised in Phoenix, so coming back to Arizona and getting the chance to apply my education while helping the community I was shaped by is a dream come true. I have a passion for plant disease research, especially when it comes to exploring how plant-pathogen interactions and genetics can be used to develop practical, empirically based disease control strategies. Let’s face it, fungicide resistance continues to emerge, yesterday’s resistant varieties grow more vulnerable every season, and the battle against plant pathogens in our fields is ongoing. But I firmly believe that when the enemy evolves, so can we.

To that end I am proud to be establishing my research program in Yuma where I will remain dedicated to improving the agricultural community’s disease management options and tackling crop health challenges. I am based out of the Yuma Agricultural Center and will continue to run the plant health diagnostic clinic located there.

Please drop off or send disease samples for diagnosis to:

Yuma Plant Health Clinic

6425 W 8th Street

Yuma, AZ 85364

If you are shipping samples, please remember to include the USDA APHIS permit for moving plant samples.

You can contact me at:

Email: cdetranaltes@arizona.edu

Cell: 602-689-7328

Office: 928-782-5879

Fig. 1. Finger weeders removing a large, in-row Palmer Amaranth plant in cotton – slow motion video. (Video credit: Kyle R. Russel, Texas A&M University. Cultivator design and setup credit: Carl Pepper, Lubbock, TX). Click here or on the image to see the video.

On Thursday February 23, 2023, the afternoon the SWAS breakout sessions dedicated to Integrated Weed Management and Impact to Desert Agriculture (Located at AS 113) will have participation from Jesse Richardson from Corteva Agriscience. He will give us the historic perspective of Kerb Chemigation research. Samuel Discua Duarte from the U of A has conducted a weed survey for INSV virus hosts for a couple of years and will inform the results in his lecture.

Jose L. Carvalho de Souza from the University of Arizona Maricopa Agricultural Center will give us a lecture on the management of Palmer amaranth, the King of weeds. And I will inform some of the results from our Prefar trials at the Yuma Agricultural Center.

You are cordially invited to the session as well as the other breakout Southwest Ag Summit sessions organized by our Arizona Vegetable IPM Team…hope to see you there!.

INTEGRATED WEED MANAGEMENT AND IMPACT TO DESERT AGRICULTURE

(Requesting 2 CEU and 2 CCA)

Location: AS 113

Sponsor: Green Valley Farm Supply, Inc.

1:30-2:00p Insights from Early Kerb Chemigation Research

Jesse Richardson, Corteva Agriscience, Mesa, AZ

2:00-2:30p Survey of Weeds as Hosts of INSV in Yuma County – Results From Two Year Survey

Samuel Discua Duarte, University of Arizona, Yuma,AZ

2:30-3:00p Integrated Weed Management – Palmer Amaranth

Jose L. Carvalho de Souza, University of Arizona, Maricopa, AZ

3:00-3:30p Herbicide Evaluations at Yuma Agricultural Center

Marco Pena, University of Arizona, Yuma, AZ

Moderated by Marco Pena

This time of year, John would often highlight Lepidopteran pests in the field and remind us of the importance of rotating insecticide modes of action. With worm pressure present in local crops, it’s a good time to revisit resistance management practices and ensure we’re protecting the effectiveness of these tools for seasons to come. For detailed guidelines, see Insecticide Resistance Management for Beet Armyworm, Cabbage Looper, and Diamondback Moth in Desert Produce Crops .

VegIPM Update Vol. 16, Num. 20

Oct. 1, 2025

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches below!!

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts declined across all traps from last collection; average for this time of year.

Beet armyworm: BAW moth increased over the last two weeks; below average for this early produce season.

Cabbage looper: Cabbage looper counts increased in the last two collections; below average for mid-late September.

Diamondback moth: a few DBM moths were caught in the traps; consistent with previous years.

Whitefly: Adult movement decreased in most locations over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.

Thrips: Thrips adult activity increased over the last two collections, typical for late September.

Aphids: Aphid movement absent so far; anticipate activity to pick up when winds begin blowing from N-NW.

Leafminers: Adult activity increased over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.