Irrigation efficiency has been receiving a lot of attention in recent months, particularly with the Colorado River system water shortages that we have been experiencing. There are several ways to define irrigation efficiency. The primary definitions for irrigation efficiency include water conveyance and delivery systems, agronomic, economic, and environmental efficiencies.

Water Conveyance and Delivery System Efficiency

In the desert Southwest we have the benefit of good engineering and infrastructure with the highly developed systems of dams, primary and secondary canals, pumps, laterals, and ditches that move water from rivers and groundwater supplies to areas of need, which are often managed by irrigation districts.

Our ability to move water from the original source to the field is a critical aspect of managing water resources and there is an “efficiency” consideration associated with that. This level of efficiency is largely a function of system engineering design, maintenance, and management.

Economic Efficiency

Economic efficiency is often considered to be the primary factor defining the financial sustainability of a farming operation. Water is a crop input and the costs associated with irrigating a crop include the costs of the water and delivery (pumps, equipment, maintenance, labor, etc.). Water is consistently the most expensive and critical input provided to a crop in Arizona and the desert Southwest. Economic efficiency essentially considers the “return on the investment” and profitability of irrigating a crop.

Environmental Efficiency

Considerations of irrigation efficiency from an environmental perspective is very broad and encompassing and it can include a combination of factors previously discussed (water conveyance systems, agronomic, and economic considerations). Environmental efficiency of an irrigation system is the product of the overall stewardship of water as a natural resource with multiple considerations for beneficial use.

Agronomic Irrigation Efficiency

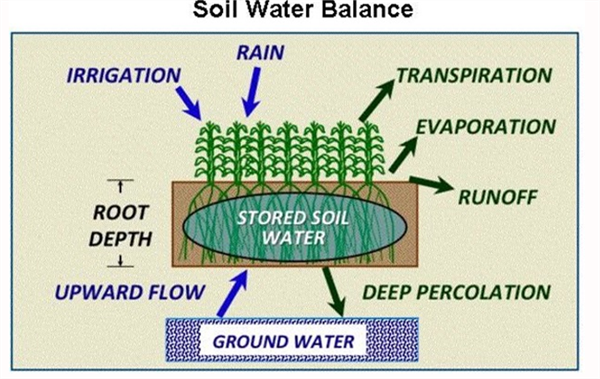

Agronomic (crop and soil) considerations are centered on our ability to provide irrigation water for the sustainable production of a crop in the field. The three primary demands for crop water management include: 1) providing water for seed germination and stand establishment, 2) providing irrigation water to match crop-consumptive water use, and 3) sufficient irrigation water to leach soluble salts from the root zone so that the soils can support crop production in a sustainable manner (Figure 1).

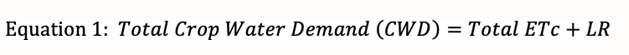

Agronomic efficiency at the field level focuses on the crop water demand (CWD) through crop consumptive use, often referred to as the crop evapotranspiration (ETc), which is the combination of evaporation and transpiration from the crop. Total crop water demand should also include the leaching requirement (LR), which is dependent upon the crop and salinity of the irrigation water.

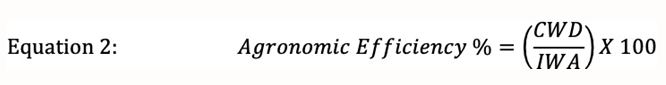

Agronomic efficiency can be estimated by considering the difference between total crop water demand, CWD and the volume of irrigation water applied (IWA).

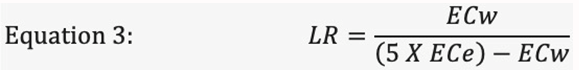

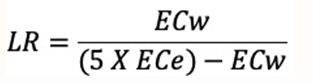

The Leaching Requirement (LR) can be estimated by use of the following calculation:

Where:

ECw = salinity of the irrigation water, electrical conductivity (dS/m)

ECe = critical plant salinity tolerance, electrical conductivity (dS/m)

This is a good method of for the LR calculation that has been utilized extensively and successfully in Arizona and the desert Southwest for many years. We can easily determine the salinity of our irrigation waters (ECw) and we can find the critical plant salinity tolerance level from open access tabulations of salinity tolerance for many crops (Ayers and Westcot, 1989). Additional direct references are from Dr. E.V. Maas’ lab at the University of California (Maas, 1984: Maas, 1986; Maas and Grattan, 1999; Maas and Grieve, 1994; and Maas and Hoffman, 1997).

Estimating Field Level Irrigation Efficiencies

The focal point of any irrigation system, from the regional, district, farm, and field levels is to provide water to produce a crop. The crop is the centerpiece of the entire operation. Therefore, it is entirely appropriate to consider irrigation efficiency at the field level in agronomic terms, by use of Equation 2.

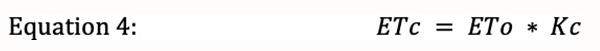

We need three factors to estimate agronomic field level irrigation efficiency for a crop: 1) crop evapotranspiration (ETc), 2) the crop and field leaching requirement (LR), and 3) a measure of the irrigation water applied (IWA) to the field in question.

To determine crop evapotranspiration (ETc) we need a good reference evapotranspiration (ETo) measurement for the field site in question. Reference evapotranspiration (ETo) values multiplied by an appropriate crop coefficient (Kc) can provide very good estimates on actual crop evapotranspiration (ETc) rates as shown in the following equation:

Reference Evapotranspiration (ETo)

The Arizona Meteorological Network (AZMET) is a system that provides both historical and real-time weather information that can be used to track reference evapotranspiration (ETo) measured at a standardized and properly calibrated weather station site. Reference evapotranspiration values can be obtained daily from AZMET for the nearly 30 sites in Arizona, including several sites in the Yuma area and the lower Colorado River Valleys.

Very importantly, the AZMET data is of a very high quality and the integrity of the system has been very well managed for over 36 years, first under the direction of Dr. Paul Brown and now with Dr. Jeremy Weiss. This information is valuable in crop water and irrigation management.

Crop Coefficients (Kc)

The appropriate crop coefficient (Kc) values are specific for each crop species and stage of growth. We commonly use crop coefficient (Kc) values that are provided in the publication “Consumptive Use by Major Crops in the Desert Southwest” by Dr. Leonard Erie and his colleagues, USDA-ARS Conservation Research Report No. 29. Crop coefficients from the publication FAO 56 “Crop Evapotranspiration-Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements-FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56” (Allen et al., 1998) are also sometimes used. Reference information for Kc values can be obtained in these publications for common crops grown in this region.

Example: Irrigation Efficiency Calculation

If we consider an example lettuce crop irrigated with water that has ECw = 1.1 dS/m and the total seasonal crop consumptive use (ETc) = 30 inches

Using Equations 1-3, an overall estimate of field level irrigation efficiency can be made. From Equation 2 we can estimate the leaching requirement (LR).

ECw = 1.1 dS/m and ECe (lettuce) = 1.3 dS/m

LR = 1.1 dS/m / (5 X 1.3) – 1.1 = 1.1/5.4 = 0.20 = 20% leaching requirement

LR = 30 X 0.2 = 6.1 ~ 6 inches

Thus, CWD = 30 + 6 = 36 inches total

For this example, we can assume: 40 inches of irrigation water was applied (IWA).

Therefore: Agronomic efficiency (from Equation 1) = 36/40 = 0.9 = 90% efficiency

Note: If the LR were not included in the total CWD, efficiency would be: 30/40 = 75%

That is an important difference and distinction to understand and demonstrate.

Irrigation efficiency has always been a major concern in the agriculture of the desert Southwest, and it always will be. The increased levels of attention being given to irrigation efficiency is good and it is important to recognize there are many factors associated with improvements in irrigation efficiency.

Figure 1. Soil-water balance and plant relationships in a crop production system.

References

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D., & Smith, M. (1998). Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. FAO, Rome, 300(9), D05109.

Ayers, R.S. and D.W. Westcot. 1989 (reprinted 1994). Water quality for agriculture. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 29 Rev. 1. ISBN 92-5-102263-1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 1985 © FAO.

https://www.fao.org/3/t0234e/t0234e00.htm

Erie, L.J., O.A French, D.A. Bucks, and K. Harris. 1981. Consumptive Use of Water by Major Crops in the Southwestern United States. United States Department of Agriculture, Conservation Research Report No. 29.

Maas, E.V. 1984. Crop tolerance to salinity. California Agriculture, October 1984. https://calag.ucanr.edu/archive/?type=pdf&article=ca.v038n10p20

Maas, E.V. 1986. Salt tolerance of plants. Appl. Agric. Res., 1, 12-36.

Maas, E.V. and S.R. Grattan. 1999. Crop yields as affected by salinity, Agricultural Drainage, Agronomy Monograph No. 38.

Maas, E. V., and Grattan, S. R. (1999). Crop yields as affected by salinity, agricultural

drainage, Agronomy Monograph No. 38, R. W.

Maas, E. V., and Grieve, C. M. 1994. “Salt tolerance of plants at different growth stages,” in Proc., Int. Conf. Current Developments in Salinity and Drought Tolerance of Plants. January 7–11, 1990, Tando Jam, Pakistan, 181–197.

Maas, E. V., and Hoffman, G. J. (1977). “Crop salt tolerance: Current assessment.”

I am seeking samples of downy mildew on lettuce from around Yuma County to support the Michelmore Lab and their ongoing efforts to help characterize the downy mildew populations of the United States. The Michelmore Lab has led the charge on a survey of Bremia variants since 1980 and has been instrumental in demystifying the gene-for-gene nature of lettuce resistance to downy mildew.

Their group invites growers across the United States to submit downy mildew infected plant samples, which are then used to culture the Bremia on live host plants. The team then inoculates a panel of lettuce varieties carrying known resistance genes to determine the race of each isolate they receive. Identifying which races occur in which specific fields is essential to guiding the breeding of new resistant cultivars and maximizing the effectiveness of host-based genetic disease management. The data obtained from these tests are also used to designate new Bremia races through the International Bremia Evaluation Board.

Your contribution will help breed better lettuce for Yuma. This means less breakdown of resistance in the field, and better yields for Yuma growers. To facilitate these submissions the Yuma Plant Health Clinic will be setting up a separate drop-off point and submission sheet for downy mildew sample submissions in the same hallway we use for standard plant diagnostic submissions. The drop-off point will be clearly labelled and consist of a chest-style refrigerator and printed copies of the submission form. It is vital to keep these samples cool so they remain viable for future inoculations, so please place your samples inside of the refrigerator before you leave.

Shipping will be handled by the clinic. All we ask is that you fill out the submission form as completely as you can. An example of the questions that are asked in that form so you can prepare ahead of time can be found HERE .For those of you interested in the latest thoughts on ag technology, you might want to check out the keynote address given by John Deere1 at CES 2023 earlier this week. The presentation can be found on YouTube at: https://youtu.be/1kjZMHZl538. As you might expect, there is a fair amount of company self-promotion, but it is interesting to hear their view on the current state and future of agricultural technologies. A couple of key takeaways for me were that telematics and computer vision systems will play key roles in the future and that increased precision will continue to be a focus.

[1] Reference to a product or company is for specific information only and does not endorse or recommend that product or company to the exclusion of others that may be suitable.