Some major events and developments have taken place in the past week in the Colorado river water shortage arena. As a result, we are entering into a series of substantial and complicated legal aspects associated with the Colorado River situation. Thus, a brief review of the current situation and some basic legal points of consideration can perhaps clarify some of the present challenges.

In November 2022 the Bureau of Reclamation (BoR) published a Notice of Intent (NOI) to analyze and prepare for the Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) regarding the “Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead” to deal with the continuing drought conditions. Since the NOI was published, representatives from the Colorado River Basin States have been meeting and working together to develop a joint Framework and Agreement Alternative and they set a target date of 1 February 2023 to submit a proposal to the BoR.

Unfortunately, the seven U.S. basin states have not been able to reach a consensus. However, six basin states, including Arizona, submitted a proposal to the BoR (1). California was not part of the six-basin state agreement and so they submitted an independent proposal for the BoR’s consideration, modeling, and analysis (2).

Now after the 1 February deadline has passed and an agreement could not be reached among all seven U.S. basin states, two sharply contrasting proposals exist.

The proposal submitted by Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming addresses a large part of the reductions of Colorado River water allocations that the BoR has targeted (2-4 million acre-feet/year, MAF/yr) by accounting for system losses that include evaporation and other losses between Lake Mead and the Imperial Dam (approximately 1.5 MAF/yr). The calculations provided in this proposal result in large reductions for California due to its large share of the river water. This proposal also addresses reductions in Colorado River allocations more rapidly than the California proposal.

The six-state plan describes collective reductions of 250,000 acre-feet (KAF) when the Lake Mead reservoir level drops to an elevation of 1,030 feet and below. The 250 KAF total would consist of 93 KAF from Arizona, 10 KAF from Nevada, and 147 KAF from California.

An additional collective reduction of 200 KAF would come from these lower basin states if Lake Mead’s elevation plunged to 1,020 feet and below.

For perspective, Lake Mead is currently at an elevation of 1,046.97 feet.

In contrast, the California proposal is heavily based on the “Law of the River” and the high-priority senior water rights of the Golden State

The current California position is consistent with earlier proposals that they have provided with an emphasis on “present perfected rights, PPRs”, their interpretation of the Law of the River, and their offer to conserve an additional 400 KAF/year through 2026. The California proposal also includes voluntary cuts of 560 KAF from Arizona and 40 KAF from Nevada. As I interpret the California proposal, I find the “voluntary” reductions from Arizona and Nevada as an interesting feature.

The California proposal also includes considerations of Lake Powell water levels and additional reductions if the elevations of that reservoir were to drop further.

What we have now is California operating alone with an argument based heavily on their interpretation of the Law of the River in contrast to the united front and a different approach to the problem presented by the six other U.S. basin states.

To understand the complexities of the current situation, some basic understanding of what the “Law of River” is, and the possible implications is important. In general, the “Law of the River” is a collection of laws, agreements, court decisions, and contracts. The Law of the River is a complex amalgam based on a series of federal laws specific to the Colorado River in combination with a series of United States Supreme Court decrees that serve to enjoin the Secretary of the Interior and the States of the Lower Division (Arizona, California, and Nevada) to a precise allocation of the water passing downriver from Hoover Dam (3, Glennon and Pearce, 2007).

Within the lower basin states there are three means by which water is allocated. First, is the allocation of water to the holder of a “present-perfected right, PPR”, consistent with a United States Supreme Court decree. The second method of water allocation is to the holder of a contract issued by the BoR under Section 5 of the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928. The third method of Colorado River water allocation is to the holder of a subcontract from a Section 5 contract holder (3, Glennon and Pearce, 2007).

The “present perfected rights PPRs” is an important aspect of the Law of the River. The PPRs are those rights to use Colorado River water that were acquired or “perfected” by prior appropriation under state law before the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 was passed.

For further delineation of water rights on the Colorado River, the BoR has established a priority ranking of water rights to administer diversions from the river on a “first-intime-first-in-right” basis.

Priority 1 consists of present perfected rights established by the decree.

Priority 2 is for federal enclaves and reserved water rights established or effective before September 30, 1968.

Priority 3 is for Section 5 contracts issued before 30 September 1968.

Priority 4 is a complex priority, consisting of (a) Section 5 contracts issued after 30 September 1968 (in a total amount not to exceed 164,652 acre-feet of annual diversions) and (b) Contract No. 14-06-W-245 issued to the Central Arizona Water Conservation District.

Priority 5 is for water within Arizona’s 2.8 MAF allocation under the decree, but not currently being used by a right holder.

Priority 6 is for Arizona’s share of any surplus allocation released by the Secretary of the Interior pursuant to the power vested in the Secretary by Article II(B)(2) of the decree. (3, Glennon and Pearce, 2007)

Most of the present perfected rights and Section 5 contracts issued before 1968 were for agricultural purposes along the mainstem of the Colorado River. Many of the Priority 4 contracts were issued to irrigation districts that were specifically formed to divert water for agricultural use. Accordingly, agricultural diversions represent 70-80% of total diversions on the Colorado River basin.

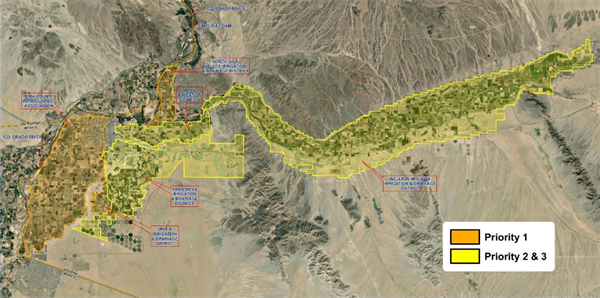

A map and general delineation of the Yuma-area irrigation districts and priority categories is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Map and delineation of the Yuma-area irrigation districts with priority

categories. Source: Yuma-area irrigation district coalition.

For the past several decades there has been increasing demand for Colorado River water for municipal and industrial (M&I) purposes, aka urban development. This has been accentuated by the rapidly growing populations of Arizona and other basin states and now compounded by the mega-drought that we have been experiencing for the 23 years.

The present situation on the Colorado River is both extremely complex and urgent. We are dealing with a real test of our system of governance, natural resource management, and our ability to deal with these challenges effectively.

While the basin states seem to be at an impasse, something and someone must give and there will be significant difficulties encountered as a result. This is a rapidly changing situation, and it will have a significant impact on agriculture in the lower Colorado River basin.

For the past several decades there has been increasing demand for Colorado River water for municipal and industrial (M&I) purposes, aka urban development. This has been accentuated by the rapidly growing populations of Arizona and other basin states and now compounded by the mega-drought that we have been experiencing for the 23 years.

The present situation on the Colorado River is both extremely complex and urgent. We are dealing with a real test of our system of governance, natural resource management, and our ability to deal with these challenges effectively.

While the basin states seem to be at an impasse, something and someone must give and there will be significant difficulties encountered as a result. This is a rapidly changing situation, and it will have a significant impact on agriculture in the lower Colorado River basin.

References

This study was conducted at the Yuma Valley Agricultural Center. The soil was a silty clay loam (7-56-37 sand-silt-clay, pH 7.2, O.M. 0.7%). Spinach ‘Meerkat’ was seeded, then sprinkler-irrigated to germinate seed Jan 13, 2025 on beds with 84 in. between bed centers and containing 30 lines of seed per bed. All irrigation water was supplied by sprinkler irrigation. Treatments were replicated four times in a randomized complete block design. Replicate plots consisted of 15 ft lengths of bed separated by 3 ft lengths of nontreated bed. Treatments were applied with a CO2 backpack sprayer that delivered 50 gal/acre at 40 psi to flat-fan nozzles.

Downy mildew (caused by Peronospora farinosa f. sp. spinaciae)was first observed in plots on Mar 5 and final reading was taken on March 6 and March 7, 2025. Spray date for each treatments are listed in excel file with the results.

Disease severity was recorded by determining the percentage of infected leaves present within three 1-ft2areas within each of the four replicate plots per treatment. The number of spinach leaves in a 1-ft2area of bed was approximately 144. The percentage were then changed to 1-10scale, with 1 being 10% infection and 10 being 100% infection.

The data (found in the accompanying Excel file) illustrate the degree of disease reduction obtained by applications of the various tested fungicides. Products that provided most effective control against the disease include Orondis ultra, Zampro, Stargus, Cevya, Eject .Please see table for other treatments with significant disease suppression/control. No phytotoxicity was observed in any of the treatments in this trial.

At last week’s 3rd AgTech Field Demo: Automated and Robotic Technologies in Yuma, AZ, 15 of the latest automated and robotic technologies were demonstrated in the field. Most were designed to control weeds in vegetable crops. Several of the technologies demonstrated are brand new to the Yuma, AZ area, still under development and/or have never been shown to a general audience. Some of the new technologies demoed included an autonomous robotic weed puller, a precision spot sprayer, and a laser weeder (Fig. 1). These technologies are intriguing and offer a different approach to automated weeding systems currently on the market. It will be interesting to see how these machines fit into our current cropping systems and evolve in the future. Obviously, to be commercially viable, the machines must be cost effective. If interested, I would be more than happy to work with you to help conduct and design experiments for assessing weeding machine performance – % weed control, hand weeding labor savings, machine work rate (acres/hour), crop yield, operating cost, etc. Please feel free to contact me anytime at siemens@cals.arizona.edu.

Fig. 1. Automated and robotic weeding technologies demonstrated at the

University of Arizona’s 3rd AgTech Field Demo included a) Nexus

Robotics’1 autonomous weeding pulling robot, b) Mantis Ag Technology’s spot

spray weeder and c) Carbon Robotics’ laser weeder.

What is the “seed bank”? It’s the reserve of viable seeds present in your soil surface or mixed with your soil at different depths. There are also other vegetative propagules that can contribute to increase your weed infestations such as tubers, solons etc.

How can we reduce our seedbank? When we fallow the fields during the summer preemergence herbicides can be applied with good results because weeds geminate after irrigations or rain.

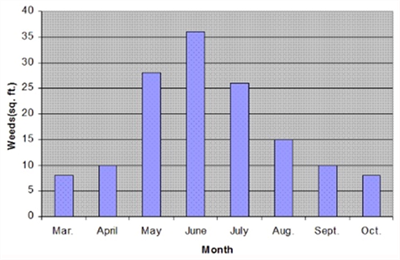

The chart here shows that summer weeds germinate starting February-March and peak germination is in June and in some cases, they continue germinating until October.

Preemergence herbicides are often used for fallow weed control only when at least 30 -45 days or longer are available1. We must take into consideration most preemergence herbicides last about 3 months depending on soil conditions. Others like Eptam may last only like 3-4 weeks because of volatility2.

Also contact herbicides like Paraquat (Gramoxone, Firestorm), Carfentrazone (Aim, Shark), Pyraflufen (ET), Pelargonic Acid (Scythe) and others are used. These products act quick and leave little or no residual but must be applied when weeds are not too large. The systemic used most frequently is still Glyphosate. It has no residual and is broad spectrum herbicide. Another product registered for fallow use is Oxifluorfen (Goal, Galigan).

Another method used for lowering the seed bank in the summer is “Solarization”. Transparent polyethylene is effective for heating the soil. It is sufficient 4-6 weeks for satisfactory control of most weeds. Some weeds are very sensitive to solar heating of the soil. Sweet clover because of hard seeds and Nutsedge because of the tubers are hard to kill with solarization. Also, Bermuda because of the rhizomes is not easy to control.

Another method is water to germinate and kill weeds mechanically or with herbicides. Some weeds like Common purslane have succulent stems and can survive after cultivation. They could re-root from the nodes and produce seeds. Therefore, carefully monitor plants to uproot them small. Tillage has a negative effect on perennials such as nutsedge and Bermuda. By repeat irrigating and disking we really are spreading them instead of killing them.

References:

WEED DYNAMICS AS INFLUENCED BY SOIL SOLARIZATION - A REVIEW R.H. Patel, Jagruti Shroff, Soumyadeep Dutta and T.G. Meisheri, Anand Agricultural University, S A College of Agriculture, Anand - 388 110, India

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches can be viewed here.

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts down in all traps over the last month; about average for December.

Beet armyworm: Moth trap counts decreased in all areas in the last 2 weeks but appear to remain active in some areas, and average for this time of the year.

Cabbage looper: Moths increased in the past 2 weeks, and average for this time of the season.

Diamondback moth: Adults increased in several locations last, particularly in the Yuma Valley most traps. Below average for December.

Whitefly: Adult movement remains low in all areas, consistent with previous years

Thrips: Thrips adult movement continues to decline, overall activity below average for December.

Aphids: Winged aphids still actively moving but declined movement in the last 2 weeks. About average for December.

Leafminers: Adult activity down in most locations, below average for this time of season.