As part of the SW Ag Summit that recently took place in Yuma, we conducted a breakout session on Thursday, 23 February 2023 titled “Colorado River Water Shortage: Agricultural Perspectives”.

This session provided a brief review of the background and current situation on the Colorado River and included perspectives from members of the lower Colorado River agricultural community including the Palo Verde Valley, Imperial Valley, and the Yuma area irrigation districts. The program outline included the following participants:

Colorado River Water Shortage: Introductory Overview

Jeff Silvertooth, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

Colorado River Water Shortage: Palo Verde Valley Perspective

Bart Fisher, Fisher Ranch, Blythe, CA

Colorado River Water Shortage: Imperial Valley Perspective

Larry Cox, Lawrence Cox Ranches, Brawley, CA

Colorado River Water Shortage: Yuma Perspective

Elston Grubaugh, Wellton Mohawk Irrigation & Drainage District, Wellton, AZ

Moderator: Jeff Silvertooth

For geographic reference, Figures 1 and 2 provide maps of the lower Colorado River Valley and Yuma agricultural irrigation districts.

The session was not recorded but we do have each of the presentations available in the following links.

Jeff Silvertooth:

https://live-azs-vegetableipmupdates.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2023-02/2023SWAS_JCS SWAS_ColoR Ag Perspectives_23feb23_FINAL_post.pdf

Bart Fisher:

https://live-azs-vegetableipmupdates.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2023-02/2023SWAS_BF_SW%20Ag%20Summit%202023.pdf

Larry Cox:

https://live-azs-vegetableipmupdates.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2023-02/2023SWAS_LC SWAS 23 February 2023.pdf

Elston Grubaugh:

https://live-azs-vegetableipmupdates.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2023-02/2023SWAS_EG_02232023%20SW%20Ag%20Summit%20Panel_0.pdf

Also posted below is the link to an excellent video regarding Yuma Water and Ag that was recently developed and presented on 23 February by the Yuma Fresh Vegetable Association.

www.yumaagwater.com

Figure 1. Map of the lower Colorado River including the dams, diversions,

and some of the major canal systems.

Figure 2. Map of the Yuma area irrigation districts. Source: Yuma Water Users Association, 2015.

I hope you are frolicking in the fields of wildflowers picking the prettiest bugs.

I was scheduled to interview for plant pathologist position at Yuma on October 18, 2019. Few weeks before that date, I emailed Dr. Palumbo asking about the agriculture system in Yuma and what will be expected of me. He sent me every information that one can think of, which at the time I thought oh how nice!

When I started the position here and saw how much he does and how much busy he stays, I was eternally grateful of the time he took to provide me all the information, especially to someone he did not know at all.

Fast forward to first month at my job someone told me that the community wants me to be the Palumbo of Plant Pathology and I remember thinking what a big thing to ask..

He was my next-door mentor, and I would stop by with questions all the time especially after passing of my predecessor Dr. Matheron. Dr. Palumbo was always there to answer any question, gave me that little boost I needed, a little courage to write that email I needed to write, a rigid answer to stand my ground if needed. And not to mention the plant diagnosis. When the submitted samples did not look like a pathogen, taking samples to his office where he would look for insects with his little handheld lenses was one of my favorite times.

I also got to work with him in couple of projects, and he would tell me “call me John”. Uhh no, that was never going to happen.. until my last interaction with him, I would fluster when I talked to him, I would get nervous to have one of my idols listening to ME? Most times, I would forget what I was going to ask but at the same time be incredibly flabbergasted by the fact that I get to work next to this legend of a man, and get his opinions about pest management. Though I really did not like giving talks after him, as honestly, I would have nothing to offer after he has talked. Every time he waved at me in a meeting, I would blush and keep smiling for minutes, and I always knew I will forever be a fangirl..

Until we meet again.

In previous articles, I have discussed using band-steam to control plant diseases and weeds. Band-steam is where, prior to planting, steam is injected in narrow bands (4” wide x 2” deep), centered on the seedline to raise soil temperatures to levels sufficient to kill weed seed and soilborne pathogens (>140 °F for >20 minutes). After the soil cools (<1 day), the crop is planted into the strips of disinfested soil.

This summer, project Co-PI, Steve Fennimore, Extension Specialist – Weed Science, UC Davis has been evaluating the efficacy of using band-steam to control weeds and cavity spot (Pythium spp.) in carrot. The trials are still in progress, but so far, the technique has been found to be very promising for weed control (Fig. 1).

Using steam to control weeds in high density crops such as carrot, baby leaf spinach and spring mix may be a particularly good fit for the method. Handing weeding in these crops is labor intensive and costs are high, typically exceeding $300/acre (Fig. 2). Costs are even greater in organic crops. A benefit of steam application is that it is organically compliant.

This fall, we will be developing a steam applicator designed for use on wide beds. We’ll be trialing the device in baby leaf spinach and spring mix. If you are interested in this application, we’ll be demonstrating weed control in baby leaf spinach using steam heat at the UA 3rd AgTech Field Day. The event will be held Tuesday, October 25th at the Yuma Ag Center.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Arizona Specialty Crop Block Grant Program and the Crop Production and Pest Management grant no. 2021-70006-35761 /project accession no. 1027435 from USDA-NIFA. We appreciate their support. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Fig. 1. Weed control with band steaming in carrot. Steam was applied in a 4-inch band centered on the two seedlines (between the dashed white lines) prior to planting. The weeds outside of the treated band can be easily removed through cultivation. (Photo credits: Steve Fennimore, UC Davis).

Fig. 2. Hand weeding in crops seeded at high densities is labor intensive.

What is the “seed bank”? It’s the reserve of viable seeds present in your soil surface or mixed with your soil at different depths. There are also other vegetative propagules that can contribute to increase your weed infestations such as tubers, solons etc.

How can we reduce our seedbank? When we fallow the fields during the summer preemergence herbicides can be applied with good results because weeds geminate after irrigations or rain.

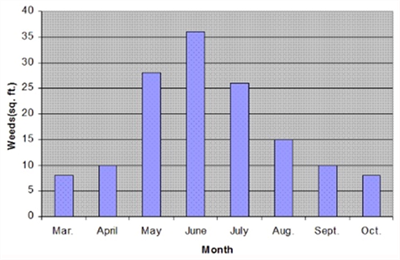

The chart here shows that summer weeds germinate starting February-March and peak germination is in June and in some cases, they continue germinating until October.

Preemergence herbicides are often used for fallow weed control only when at least 30 -45 days or longer are available1. We must take into consideration most preemergence herbicides last about 3 months depending on soil conditions. Others like Eptam may last only like 3-4 weeks because of volatility2.

Also contact herbicides like Paraquat (Gramoxone, Firestorm), Carfentrazone (Aim, Shark), Pyraflufen (ET), Pelargonic Acid (Scythe) and others are used. These products act quick and leave little or no residual but must be applied when weeds are not too large. The systemic used most frequently is still Glyphosate. It has no residual and is broad spectrum herbicide. Another product registered for fallow use is Oxifluorfen (Goal, Galigan).

Another method used for lowering the seed bank in the summer is “Solarization”. Transparent polyethylene is effective for heating the soil. It is sufficient 4-6 weeks for satisfactory control of most weeds. Some weeds are very sensitive to solar heating of the soil. Sweet clover because of hard seeds and Nutsedge because of the tubers are hard to kill with solarization. Also, Bermuda because of the rhizomes is not easy to control.

Another method is water to germinate and kill weeds mechanically or with herbicides. Some weeds like Common purslane have succulent stems and can survive after cultivation. They could re-root from the nodes and produce seeds. Therefore, carefully monitor plants to uproot them small. Tillage has a negative effect on perennials such as nutsedge and Bermuda. By repeat irrigating and disking we really are spreading them instead of killing them.

References:

WEED DYNAMICS AS INFLUENCED BY SOIL SOLARIZATION - A REVIEW R.H. Patel, Jagruti Shroff, Soumyadeep Dutta and T.G. Meisheri, Anand Agricultural University, S A College of Agriculture, Anand - 388 110, India