As part of the SW Ag Summit that recently took place in Yuma, we conducted a breakout session on Thursday, 23 February 2023 titled “Colorado River Water Shortage: Agricultural Perspectives”.

This session provided a brief review of the background and current situation on the Colorado River and included perspectives from members of the lower Colorado River agricultural community including the Palo Verde Valley, Imperial Valley, and the Yuma area irrigation districts. The program outline included the following participants:

Colorado River Water Shortage: Introductory Overview

Jeff Silvertooth, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

Colorado River Water Shortage: Palo Verde Valley Perspective

Bart Fisher, Fisher Ranch, Blythe, CA

Colorado River Water Shortage: Imperial Valley Perspective

Larry Cox, Lawrence Cox Ranches, Brawley, CA

Colorado River Water Shortage: Yuma Perspective

Elston Grubaugh, Wellton Mohawk Irrigation & Drainage District, Wellton, AZ

Moderator: Jeff Silvertooth

For geographic reference, Figures 1 and 2 provide maps of the lower Colorado River Valley and Yuma agricultural irrigation districts.

The session was not recorded but we do have each of the presentations available in the following links.

Jeff Silvertooth:

https://live-azs-vegetableipmupdates.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2023-02/2023SWAS_JCS SWAS_ColoR Ag Perspectives_23feb23_FINAL_post.pdf

Bart Fisher:

https://live-azs-vegetableipmupdates.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2023-02/2023SWAS_BF_SW%20Ag%20Summit%202023.pdf

Larry Cox:

https://live-azs-vegetableipmupdates.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2023-02/2023SWAS_LC SWAS 23 February 2023.pdf

Elston Grubaugh:

https://live-azs-vegetableipmupdates.pantheonsite.io/sites/default/files/2023-02/2023SWAS_EG_02232023%20SW%20Ag%20Summit%20Panel_0.pdf

Also posted below is the link to an excellent video regarding Yuma Water and Ag that was recently developed and presented on 23 February by the Yuma Fresh Vegetable Association.

www.yumaagwater.com

Figure 1. Map of the lower Colorado River including the dams, diversions,

and some of the major canal systems.

Figure 2. Map of the Yuma area irrigation districts. Source: Yuma Water Users Association, 2015.

Hi, I’m Chris, and I’m thrilled to be stepping into the role of extension associate for plant pathology through The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension in Yuma County. I recently earned my Ph.D. in plant pathology from Purdue University in Indiana where my research focused on soybean seedling disease caused by Fusarium and Pythium. There, I discovered and characterized some of the first genetic resources available for improving innate host resistance and genetic control to two major pathogens causing this disease in soybean across the Midwest.

I was originally born and raised in Phoenix, so coming back to Arizona and getting the chance to apply my education while helping the community I was shaped by is a dream come true. I have a passion for plant disease research, especially when it comes to exploring how plant-pathogen interactions and genetics can be used to develop practical, empirically based disease control strategies. Let’s face it, fungicide resistance continues to emerge, yesterday’s resistant varieties grow more vulnerable every season, and the battle against plant pathogens in our fields is ongoing. But I firmly believe that when the enemy evolves, so can we.

To that end I am proud to be establishing my research program in Yuma where I will remain dedicated to improving the agricultural community’s disease management options and tackling crop health challenges. I am based out of the Yuma Agricultural Center and will continue to run the plant health diagnostic clinic located there.

Please drop off or send disease samples for diagnosis to:

Yuma Plant Health Clinic

6425 W 8th Street

Yuma, AZ 85364

If you are shipping samples, please remember to include the USDA APHIS permit for moving plant samples.

You can contact me at:

Email: cdetranaltes@arizona.edu

Cell: 602-689-7328

Office: 928-782-5879

In previous articles, I have discussed using band-steam to control plant diseases and weeds. Band-steam is where, prior to planting, steam is injected in narrow bands (4” wide x 2” deep), centered on the seedline to raise soil temperatures to levels sufficient to kill weed seed and soilborne pathogens (>140 °F for >20 minutes). After the soil cools (<1 day), the crop is planted into the strips of disinfested soil.

This summer, project Co-PI, Steve Fennimore, Extension Specialist – Weed Science, UC Davis has been evaluating the efficacy of using band-steam to control weeds and cavity spot (Pythium spp.) in carrot. The trials are still in progress, but so far, the technique has been found to be very promising for weed control (Fig. 1).

Using steam to control weeds in high density crops such as carrot, baby leaf spinach and spring mix may be a particularly good fit for the method. Handing weeding in these crops is labor intensive and costs are high, typically exceeding $300/acre (Fig. 2). Costs are even greater in organic crops. A benefit of steam application is that it is organically compliant.

This fall, we will be developing a steam applicator designed for use on wide beds. We’ll be trialing the device in baby leaf spinach and spring mix. If you are interested in this application, we’ll be demonstrating weed control in baby leaf spinach using steam heat at the UA 3rd AgTech Field Day. The event will be held Tuesday, October 25th at the Yuma Ag Center.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Arizona Specialty Crop Block Grant Program and the Crop Production and Pest Management grant no. 2021-70006-35761 /project accession no. 1027435 from USDA-NIFA. We appreciate their support. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Fig. 1. Weed control with band steaming in carrot. Steam was applied in a 4-inch band centered on the two seedlines (between the dashed white lines) prior to planting. The weeds outside of the treated band can be easily removed through cultivation. (Photo credits: Steve Fennimore, UC Davis).

Fig. 2. Hand weeding in crops seeded at high densities is labor intensive.

What is the “seed bank”? It’s the reserve of viable seeds present in your soil surface or mixed with your soil at different depths. There are also other vegetative propagules that can contribute to increase your weed infestations such as tubers, solons etc.

How can we reduce our seedbank? When we fallow the fields during the summer preemergence herbicides can be applied with good results because weeds geminate after irrigations or rain.

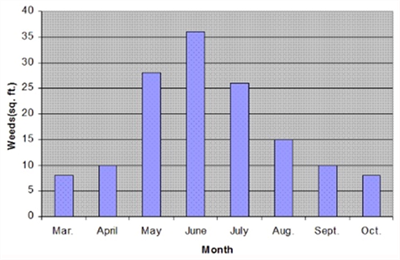

The chart here shows that summer weeds germinate starting February-March and peak germination is in June and in some cases, they continue germinating until October.

Preemergence herbicides are often used for fallow weed control only when at least 30 -45 days or longer are available1. We must take into consideration most preemergence herbicides last about 3 months depending on soil conditions. Others like Eptam may last only like 3-4 weeks because of volatility2.

Also contact herbicides like Paraquat (Gramoxone, Firestorm), Carfentrazone (Aim, Shark), Pyraflufen (ET), Pelargonic Acid (Scythe) and others are used. These products act quick and leave little or no residual but must be applied when weeds are not too large. The systemic used most frequently is still Glyphosate. It has no residual and is broad spectrum herbicide. Another product registered for fallow use is Oxifluorfen (Goal, Galigan).

Another method used for lowering the seed bank in the summer is “Solarization”. Transparent polyethylene is effective for heating the soil. It is sufficient 4-6 weeks for satisfactory control of most weeds. Some weeds are very sensitive to solar heating of the soil. Sweet clover because of hard seeds and Nutsedge because of the tubers are hard to kill with solarization. Also, Bermuda because of the rhizomes is not easy to control.

Another method is water to germinate and kill weeds mechanically or with herbicides. Some weeds like Common purslane have succulent stems and can survive after cultivation. They could re-root from the nodes and produce seeds. Therefore, carefully monitor plants to uproot them small. Tillage has a negative effect on perennials such as nutsedge and Bermuda. By repeat irrigating and disking we really are spreading them instead of killing them.

References:

WEED DYNAMICS AS INFLUENCED BY SOIL SOLARIZATION - A REVIEW R.H. Patel, Jagruti Shroff, Soumyadeep Dutta and T.G. Meisheri, Anand Agricultural University, S A College of Agriculture, Anand - 388 110, India

This time of year, John would often highlight Lepidopteran pests in the field and remind us of the importance of rotating insecticide modes of action. With worm pressure present in local crops, it’s a good time to revisit resistance management practices and ensure we’re protecting the effectiveness of these tools for seasons to come. For detailed guidelines, see Insecticide Resistance Management for Beet Armyworm, Cabbage Looper, and Diamondback Moth in Desert Produce Crops .

VegIPM Update Vol. 16, Num. 20

Oct. 1, 2025

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches below!!

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts declined across all traps from last collection; average for this time of year.

Beet armyworm: BAW moth increased over the last two weeks; below average for this early produce season.

Cabbage looper: Cabbage looper counts increased in the last two collections; below average for mid-late September.

Diamondback moth: a few DBM moths were caught in the traps; consistent with previous years.

Whitefly: Adult movement decreased in most locations over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.

Thrips: Thrips adult activity increased over the last two collections, typical for late September.

Aphids: Aphid movement absent so far; anticipate activity to pick up when winds begin blowing from N-NW.

Leafminers: Adult activity increased over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.