Some major events and developments have taken place in the past week in the Colorado river water shortage arena. As a result, we are entering into a series of substantial and complicated legal aspects associated with the Colorado River situation. Thus, a brief review of the current situation and some basic legal points of consideration can perhaps clarify some of the present challenges.

In November 2022 the Bureau of Reclamation (BoR) published a Notice of Intent (NOI) to analyze and prepare for the Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) regarding the “Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead” to deal with the continuing drought conditions. Since the NOI was published, representatives from the Colorado River Basin States have been meeting and working together to develop a joint Framework and Agreement Alternative and they set a target date of 1 February 2023 to submit a proposal to the BoR.

Unfortunately, the seven U.S. basin states have not been able to reach a consensus. However, six basin states, including Arizona, submitted a proposal to the BoR (1). California was not part of the six-basin state agreement and so they submitted an independent proposal for the BoR’s consideration, modeling, and analysis (2).

Now after the 1 February deadline has passed and an agreement could not be reached among all seven U.S. basin states, two sharply contrasting proposals exist.

The proposal submitted by Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming addresses a large part of the reductions of Colorado River water allocations that the BoR has targeted (2-4 million acre-feet/year, MAF/yr) by accounting for system losses that include evaporation and other losses between Lake Mead and the Imperial Dam (approximately 1.5 MAF/yr). The calculations provided in this proposal result in large reductions for California due to its large share of the river water. This proposal also addresses reductions in Colorado River allocations more rapidly than the California proposal.

The six-state plan describes collective reductions of 250,000 acre-feet (KAF) when the Lake Mead reservoir level drops to an elevation of 1,030 feet and below. The 250 KAF total would consist of 93 KAF from Arizona, 10 KAF from Nevada, and 147 KAF from California.

An additional collective reduction of 200 KAF would come from these lower basin states if Lake Mead’s elevation plunged to 1,020 feet and below.

For perspective, Lake Mead is currently at an elevation of 1,046.97 feet.

In contrast, the California proposal is heavily based on the “Law of the River” and the high-priority senior water rights of the Golden State

The current California position is consistent with earlier proposals that they have provided with an emphasis on “present perfected rights, PPRs”, their interpretation of the Law of the River, and their offer to conserve an additional 400 KAF/year through 2026. The California proposal also includes voluntary cuts of 560 KAF from Arizona and 40 KAF from Nevada. As I interpret the California proposal, I find the “voluntary” reductions from Arizona and Nevada as an interesting feature.

The California proposal also includes considerations of Lake Powell water levels and additional reductions if the elevations of that reservoir were to drop further.

What we have now is California operating alone with an argument based heavily on their interpretation of the Law of the River in contrast to the united front and a different approach to the problem presented by the six other U.S. basin states.

To understand the complexities of the current situation, some basic understanding of what the “Law of River” is, and the possible implications is important. In general, the “Law of the River” is a collection of laws, agreements, court decisions, and contracts. The Law of the River is a complex amalgam based on a series of federal laws specific to the Colorado River in combination with a series of United States Supreme Court decrees that serve to enjoin the Secretary of the Interior and the States of the Lower Division (Arizona, California, and Nevada) to a precise allocation of the water passing downriver from Hoover Dam (3, Glennon and Pearce, 2007).

Within the lower basin states there are three means by which water is allocated. First, is the allocation of water to the holder of a “present-perfected right, PPR”, consistent with a United States Supreme Court decree. The second method of water allocation is to the holder of a contract issued by the BoR under Section 5 of the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928. The third method of Colorado River water allocation is to the holder of a subcontract from a Section 5 contract holder (3, Glennon and Pearce, 2007).

The “present perfected rights PPRs” is an important aspect of the Law of the River. The PPRs are those rights to use Colorado River water that were acquired or “perfected” by prior appropriation under state law before the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 was passed.

For further delineation of water rights on the Colorado River, the BoR has established a priority ranking of water rights to administer diversions from the river on a “first-intime-first-in-right” basis.

Priority 1 consists of present perfected rights established by the decree.

Priority 2 is for federal enclaves and reserved water rights established or effective before September 30, 1968.

Priority 3 is for Section 5 contracts issued before 30 September 1968.

Priority 4 is a complex priority, consisting of (a) Section 5 contracts issued after 30 September 1968 (in a total amount not to exceed 164,652 acre-feet of annual diversions) and (b) Contract No. 14-06-W-245 issued to the Central Arizona Water Conservation District.

Priority 5 is for water within Arizona’s 2.8 MAF allocation under the decree, but not currently being used by a right holder.

Priority 6 is for Arizona’s share of any surplus allocation released by the Secretary of the Interior pursuant to the power vested in the Secretary by Article II(B)(2) of the decree. (3, Glennon and Pearce, 2007)

Most of the present perfected rights and Section 5 contracts issued before 1968 were for agricultural purposes along the mainstem of the Colorado River. Many of the Priority 4 contracts were issued to irrigation districts that were specifically formed to divert water for agricultural use. Accordingly, agricultural diversions represent 70-80% of total diversions on the Colorado River basin.

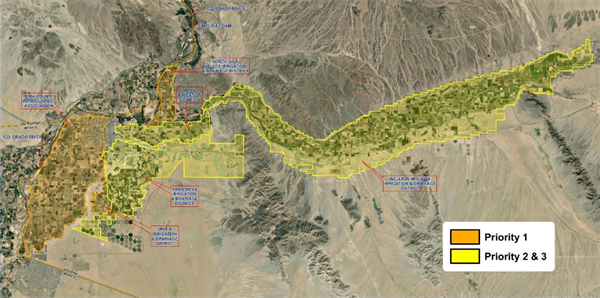

A map and general delineation of the Yuma-area irrigation districts and priority categories is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Map and delineation of the Yuma-area irrigation districts with priority

categories. Source: Yuma-area irrigation district coalition.

For the past several decades there has been increasing demand for Colorado River water for municipal and industrial (M&I) purposes, aka urban development. This has been accentuated by the rapidly growing populations of Arizona and other basin states and now compounded by the mega-drought that we have been experiencing for the 23 years.

The present situation on the Colorado River is both extremely complex and urgent. We are dealing with a real test of our system of governance, natural resource management, and our ability to deal with these challenges effectively.

While the basin states seem to be at an impasse, something and someone must give and there will be significant difficulties encountered as a result. This is a rapidly changing situation, and it will have a significant impact on agriculture in the lower Colorado River basin.

For the past several decades there has been increasing demand for Colorado River water for municipal and industrial (M&I) purposes, aka urban development. This has been accentuated by the rapidly growing populations of Arizona and other basin states and now compounded by the mega-drought that we have been experiencing for the 23 years.

The present situation on the Colorado River is both extremely complex and urgent. We are dealing with a real test of our system of governance, natural resource management, and our ability to deal with these challenges effectively.

While the basin states seem to be at an impasse, something and someone must give and there will be significant difficulties encountered as a result. This is a rapidly changing situation, and it will have a significant impact on agriculture in the lower Colorado River basin.

References

Hi, I’m Chris, and I’m thrilled to be stepping into the role of extension associate for plant pathology through The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension in Yuma County. I recently earned my Ph.D. in plant pathology from Purdue University in Indiana where my research focused on soybean seedling disease caused by Fusarium and Pythium. There, I discovered and characterized some of the first genetic resources available for improving innate host resistance and genetic control to two major pathogens causing this disease in soybean across the Midwest.

I was originally born and raised in Phoenix, so coming back to Arizona and getting the chance to apply my education while helping the community I was shaped by is a dream come true. I have a passion for plant disease research, especially when it comes to exploring how plant-pathogen interactions and genetics can be used to develop practical, empirically based disease control strategies. Let’s face it, fungicide resistance continues to emerge, yesterday’s resistant varieties grow more vulnerable every season, and the battle against plant pathogens in our fields is ongoing. But I firmly believe that when the enemy evolves, so can we.

To that end I am proud to be establishing my research program in Yuma where I will remain dedicated to improving the agricultural community’s disease management options and tackling crop health challenges. I am based out of the Yuma Agricultural Center and will continue to run the plant health diagnostic clinic located there.

Please drop off or send disease samples for diagnosis to:

Yuma Plant Health Clinic

6425 W 8th Street

Yuma, AZ 85364

If you are shipping samples, please remember to include the USDA APHIS permit for moving plant samples.

You can contact me at:

Email: cdetranaltes@arizona.edu

Cell: 602-689-7328

Office: 928-782-5879

We are in the process or organizing our 3rd AgTech Field Day. The event will be held Tuesday, October 25th at the University of Arizona’s Yuma Agricultural Center. Like last year, the workshop will feature the latest ag technologies being demoed in the field. I’ve been reaching out to multiple companies but am sure I’m not aware of all the cutting-edge technologies out there. We’d like to showcase as many innovative ag technologies as possible, so please contact me if you are interested in demoing your equipment or know someone that is. It’s an open invitation - private companies, and university and government researchers are all welcome.

Fig. 1. AgTech Field Day (2021).

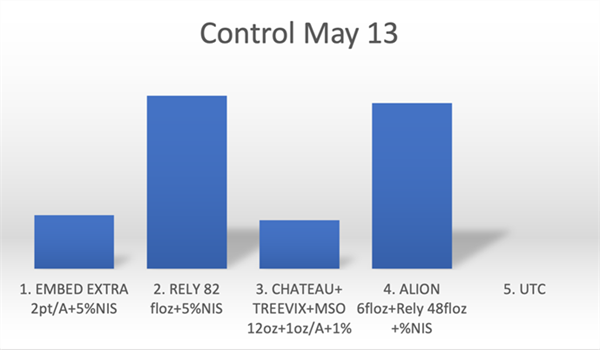

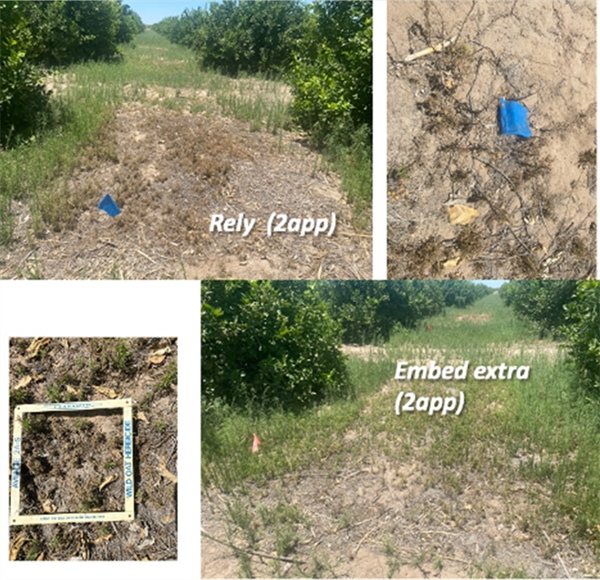

Overreliance in glyphosate could increase the risk of reduced efficacy of this herbicide. Some the weeds difficult to control with glyphosate in our area are: Hairy fleabane (Coniza bonariensis), Horseweed (Coniza canadiensis), White sweet clover (Melilotus albus). Pig weed (Amaranthus palmeri), and Cheeseweed (Malva parviflora). We are conducting experiments in the Yuma area to identify effective herbicide control options for Hairy fleabane. Some research done in Australia has shown that Fleabane cannot be controlled with a single herbicide treatment even with knockdown herbicides such as paraquat + diquat, and researchers suggest the need of combinations of different modes of action to achieve control effectively1. In one fleabane evaluation started May 6, 2022, we included the following treatments: 1. Embed Extra 2pt/A+5%NIS 2. Rely 82 floz+5%NIS 3. Chateau+ Treevix+MSO (12oz+1oz/A+1%)

We noticed treatments including Glufosinate (Rely) showed best burndown activity, but regrowth was observed in two weeks (13-14 plants per ft2). So, a second application was performed on three weeks after first on the Rely plots.

The grower and PCA informs us that Sulfenacil (Sharpen) has worked effectively for them with sequential applications. Additionally, we are evaluating Suppress and Clopyralid in the same location.

You are always welcomed to send your comments, suggestions to the IPM Team. Let us know what you are doing and your findings. We know there is a researcher in every grower and PCA and your input is greatly appreciated.

This time of year, John would often highlight Lepidopteran pests in the field and remind us of the importance of rotating insecticide modes of action. With worm pressure present in local crops, it’s a good time to revisit resistance management practices and ensure we’re protecting the effectiveness of these tools for seasons to come. For detailed guidelines, see Insecticide Resistance Management for Beet Armyworm, Cabbage Looper, and Diamondback Moth in Desert Produce Crops .

VegIPM Update Vol. 16, Num. 20

Oct. 1, 2025

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches below!!

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts declined across all traps from last collection; average for this time of year.

Beet armyworm: BAW moth increased over the last two weeks; below average for this early produce season.

Cabbage looper: Cabbage looper counts increased in the last two collections; below average for mid-late September.

Diamondback moth: a few DBM moths were caught in the traps; consistent with previous years.

Whitefly: Adult movement decreased in most locations over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.

Thrips: Thrips adult activity increased over the last two collections, typical for late September.

Aphids: Aphid movement absent so far; anticipate activity to pick up when winds begin blowing from N-NW.

Leafminers: Adult activity increased over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.