Southwester Chile Production

The Southwestern (SW) Chile Belt extends from southeast Arizona, across southern New Mexico, into far-west Texas, and northern Chihuahua, Mexico. The SW Chile Belt is dominated by production of New Mexico-type chile, also commonly referred to as “Hatch chile” and also sometimes referred to as “Anaheim” type chile.

Recent acreages across the SW Chile Belt have consisted of approximately 7-8,000 acres in NM, 3-4,000 in TX, approximately 90,000 acres in Chihuahua, and about 300-500 acres in Arizona. Chiles are often associated with New Mexico, but Arizona also has a strong connection to this chile industry. For example, the Curry Chile Seed Company, based in Pearce, AZ, provides the seed for >90% of the total green chile acreage across the SW Chile Belt.

Chile peppers (Capsicum species) are among the first crops domesticated in the Western Hemisphere about 10,000 BCE (Perry et al., 2007). The Capsicum genus became important to people and as result, five different Capsicum species that were independently domesticated in various regions of the Americas (Bosland &Votava, 2012). Early domestication of chile peppers by indigenous peoples was commonly driven for use as medicinal plants. Due to their flavor and heat characteristics, chile peppers are a populate food ingredient in many parts of the world, including Latin America, Africa, and Asia cuisines. Chiles have been increasingly important to the U.S. and European food industries, particularly as these populations become more familiar with chile (Guzman and Bosland, 2017).

There are five domesticated species of chile peppers. 1) Capsicum annuum is probably the most common to us and it includes many common varieties such as bell peppers, wax, cayenne, jalapeños, Thai peppers, chiltepin, and all forms of New Mexico chile. 2) Capsicum frutescens includes malagueta, tabasco, piri piri, and Malawian Kambuzi. 3)Capsicum chinense includes what many consider the hottest peppers such as the naga, habanero, Datil, and Scotch bonnet. 4) Capsicum pubescens includes the South American rocoto peppers. 5) Capsicum baccatum includes the South American aji peppers.

The Capsicum annuum species is the most common group of chiles that we encounter and there are at least 14 very different pod types in this single species that includes: New Mexico (aka Anaheim), bell peppers, cayennes, jalapeños, paprika, serrano, pequin, pimiento, yellow wax, tomato, cherry, cascabel, ancho (mulato, pasilla), and guajillo (Guzman and Bosland, 2017).

Crop Phenology

Plants vary tremendously in their physiological behavior over the course of their life cycles. As plants change physiologically and morphologically through their various stages of growth, water and nutritional requirements will change considerably as well. Efficient management of a crop requires an understanding of the relationship between morphological and physiological changes that are taking place and the input requirements.

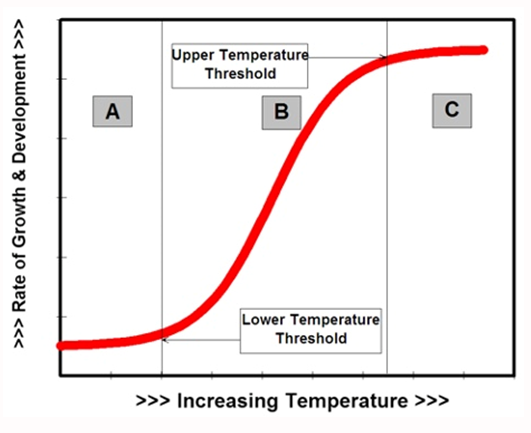

Heat units (HUs) can be used as a management tool for more efficient timing of irrigation and nutrient inputs to a crop and also pest management strategies. Plants will develop over a range of temperatures which is defined by the lower and upper temperature thresholds for growth (Figure 1). Heat unit systems consider the elapsed time that local temperatures fall within the set upper and lower temperature thresholds and thereby provide an estimate of the expected rate of development for the crop. Heat units systems have largely replaced days after planting in crop phenology models because they take into account day-to-day fluctuations in temperature. Phenology models describe how crop growth and development are impacted by weather and climate and provide an effective way to standardize crop growth and development among different years and across many locations (Baskerville and Emin, 1969; Brown, 1989).

The use of HU-based phenology models are particularly important and applicable in irrigated crop production systems where water is a non-limiting factor. Water stress will alter phenological plant development and it is a major source of variation in crop development models. Accordingly, irrigated systems are more consistent in crop development patterns and HU models can be much more consistent and reliable.

Chiles are a warm season, perennial plant with an indeterminant growth habit that we grow and manage as an annual crop. The fruiting cycle begins at the crown stage of growth and continues until the plant reaches a point of “cut-out” with hiatus in blooming as the plant works to mature the chile fruit crop that has been developed.

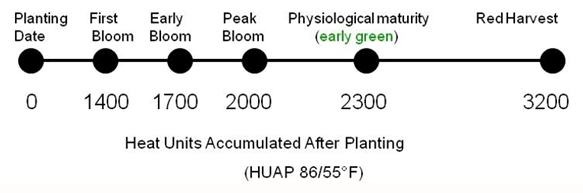

The first step in developing a phenological guideline for chiles would be to look for critical stages of growth in relation to HU accumulation. Figure 2 describes the basic phenological baseline for New Mexico – type chile and was developed from field studies conducted in New Mexico and Arizona (Silvertooth et al., 2010 and 2011; Soto et al., 2006; and Soto and Silvertooth, 2007).

Water and nutrient demands coincide with the fruiting cycle and efficient management of irrigation water and plant nutrients is enhanced by tracking crop development in the field. The use of HUs (86/55 oF thresholds) can be applied since the thermal environment impacts the development of all crop systems, including chiles, (Figures 2 and 3).

Use of HUs to predict chile development is considered superior to using days after planting due to the simple fact that the crop responds to environmental conditions and not calendar days. This approach, using phenological timelines or baselines, works best for irrigated conditions where crop vigor and environmental growth conditions are more consistent than in non-irrigated or dryland situations where irregularity in year-to-year rainfall patterns can alter growth and development patterns significantly.

Crop Phenology Relationship to Nutrient and Water Demand

Phenological guidelines can be used to identify or predict important stages of crop development that impact physiological requirements. For example, a phenological guideline can help identify stages of growth in relation to crop water use (consumptive use) and nutrient uptake patterns. This information allows growers to improve the timing of water and nutrient inputs to improve production efficiency. For some crops or production situations HU based phenological guidelines can be used to project critical dates such as harvest or crop termination. Many other applications related to crop management (e.g., pest management) can be derived from a better understanding of crop growth and development patterns.

ADDITIONAL NOTE:

Arizona Hosts the 2022 International Pepper Conference (IPC), 26-28 September 2022, Tucson and Pearce, Arizona.

Registration for the International Pepper Conference. Registration and additional information can be found at https://extension.arizona.edu/ipc/

Here’s a note from the conference Chair and Host, Mr. Ed Curry:

With the final countdown to the 25th biennial International Pepper Conference just days away, we want to encourage everyone who grows, processes, conducts research, educates about, or just enjoys chile peppers to get on board!

The early bird pre-registration discount ends August 26th!

We are also excited to announce that for anyone interested in only the field day portion of the event (Sep. 27th), a stand-alone, one-day registration is available for $200 with walk up/ same day attendees welcome!

The conference will have an active schedule with many educational opportunities including:

• Farm level breeding programs

• Mechanical harvest technology

• Pepper diseases and their management

• Basic crop management science, heat units, fertility, and irrigation protocols – Dr. Jeff Silvertooth, University of Arizona

• Breeding mechanical harvest type plants with Dr. Stephanie Walker, New Mexico State University

• How to grow any type of PEPPER for mechanical harvest with Dr. Ben Villalon, Texas A&M Professor Emeritus

• Disease prevention at a molecular level with Dr. Steve Hansen, New Mexico State University

• Pepper flavor at the molecular level with Dr. Randy Hauptmann, BioGold LLC

• Biopharmaceuticals at a molecular level with Dr. Bhimu Patel, Texas A&M

And the list goes on......

What we hope to encapsulate in our program is the integration of basic on-farm agriculture and advanced technologies to demonstrate the importance of both approaches in moving forward the multifaceted and beautiful world of 🌶PEPPER!

WE CORDIALLY INVITE ANY AND ALL PARTICIPANTS. WALK UP REGISTRATIONS WILL BE WELCOME! I AM EXCITED TO SEE YOU THERE!

YOUR HOST OF THE 2022 INTERNATIONAL PEPPER CONFERENCE,

ED CURRY

Figure 1. Typical relationship between the rate of plant growth and

development and temperature. Growth and development ceases when

temperatures decline below the lower temperature threshold (A) or increase

above the upper temperature threshold (C). Growth and development increases

rapidly when temperatures fall between the lower and upper temperature

thresholds (B).

Figure 2. Basic phenological guideline for irrigated New Mexico-type chiles.

References

Baskerville, G.L. and P. Emin. 1969. Rapid estimation of heat accumulation from maximum and minimum temperatures. Ecology 50:514-517.

Bosland, P.W., E.J. Votava, and E.M. Votava. 2012. Peppers: Vegetable and spice capsicums. Wallingford, U.K.: CAB Intl.

Brown, P. W. 1989. Heat units. Bull. 8915, Univ. of Arizona Cooperative Extension, College of Ag., Tucson, AZ.

Guzmán, I. and P.W. Bosland. 2017. Sensory properties of chile pepper heat - and its importance to food quality and cultural preference. Appetite, 2017 Oct 1;117:186-190. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.06.026.

Perry, L., Dickau, R., Zarrillo, S., Holst, I., Pearsall, D. M., Piperno, D. R., et al. 2007. Starch fossils and the domestication and dispersal of chili peppers (Capsicum spp. L.) in the Americas. Science, 315, 986-988.

Silvertooth, J.C., P.W. Brown, and S. Walker. 2010. Crop Growth and Development for Irrigated Chile (Capsicum annuum). University of Arizona Cooperative Extension Bulletin No. AZ 1529

Silvertooth, J.C., P.W. Brown and S.Walker. 2011. Crop Growth and Development for Irrigated Chile (Capsicum annuum). New Mexico Chile Association, Report 32. New Mexico State University, College of Agriculture, Consumer and Environmental Science.

Soto-Ortiz, Roberto, J.C. Silvertooth, and A. Galadima. 2006. Crop Phenology for Irrigated Chiles (Capsicum annuum L.) in Arizona and New Mexico. Vegetable Report, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Report Series P-144, November, University of Arizona.

Soto-Ortiz, R. and J.C. Silvertooth. 2007. A Crop Phenology Model for Irrigated New Mexico Chile (Capsicum annuum L.) The 2007 Vegetable Report. Jan 08:104-122.

I hope you are frolicking in the fields of wildflowers picking the prettiest bugs.

I was scheduled to interview for plant pathologist position at Yuma on October 18, 2019. Few weeks before that date, I emailed Dr. Palumbo asking about the agriculture system in Yuma and what will be expected of me. He sent me every information that one can think of, which at the time I thought oh how nice!

When I started the position here and saw how much he does and how much busy he stays, I was eternally grateful of the time he took to provide me all the information, especially to someone he did not know at all.

Fast forward to first month at my job someone told me that the community wants me to be the Palumbo of Plant Pathology and I remember thinking what a big thing to ask..

He was my next-door mentor, and I would stop by with questions all the time especially after passing of my predecessor Dr. Matheron. Dr. Palumbo was always there to answer any question, gave me that little boost I needed, a little courage to write that email I needed to write, a rigid answer to stand my ground if needed. And not to mention the plant diagnosis. When the submitted samples did not look like a pathogen, taking samples to his office where he would look for insects with his little handheld lenses was one of my favorite times.

I also got to work with him in couple of projects, and he would tell me “call me John”. Uhh no, that was never going to happen.. until my last interaction with him, I would fluster when I talked to him, I would get nervous to have one of my idols listening to ME? Most times, I would forget what I was going to ask but at the same time be incredibly flabbergasted by the fact that I get to work next to this legend of a man, and get his opinions about pest management. Though I really did not like giving talks after him, as honestly, I would have nothing to offer after he has talked. Every time he waved at me in a meeting, I would blush and keep smiling for minutes, and I always knew I will forever be a fangirl..

Until we meet again.

Vol. 13, Issue 07, Published 4/6/2022

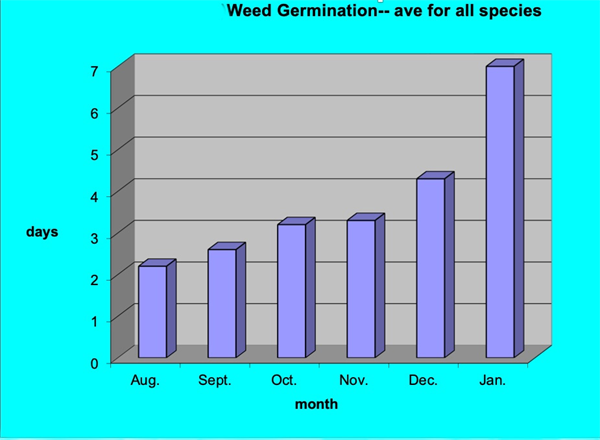

Finger weeders are an in-row weeding tool made out of flexible rubber. Pairs are centered on the seed row and overlapped slightly to remove in-row weeds. Our experience has been that they are effective at removing small (3-4 leaf) weeds, but not large or well anchored large weeds. A Texas A&M University colleague shared that they were able to regularly remove 3-4 inch tall Palmer Amaranth in cotton with a cultivator configuration developed by organic cotton grower Carl Pepper. I was pretty impressed. I think you will be too. Check it out by clicking here or on the image below.Preemergence herbicides can be very effective in the low deserts where weeds germinate with every irrigation or rainfall. It is essential, however, that they be at the right place in the soil at the right time. The right place is in the soil around the weed seeds and the right time is when they are germinating. Only fumigants kill seeds. For most other herbicides, the seed must germinate and are then killed. When weed seeds germinate is dependent on a great number of interdependent variables. These include weed species, soil type, moisture, soil temperature, condition of the seed, depth, organic matter and many other variables. Many seeds have biochemical mechanisms that allow them to germinate at different times. Some may germinate in a few hours and some may not germinate for several years. If they all germinated at the same time, they would be easier to control. The methods used to predict when weed seeds will germinate vary from very sophisticated numeric equations to Farmers Almanac type lore involving things like the thickness of gopher fur, the cuticle thickness of plants or the condition of bird feathers. Some methods will give you a precise day while others will give you just a general idea. In general, as the precision goes up, the accuracy goes down. Regardless of what technique you use, now is the best time to apply preemergence herbicides for the control of annual weeds. It is better to be a month early than a day late.We have conducted trials to determine how long it takes various weed species to germinate after receiving moisture. Results will vary depending on several factors and from field to field and year to year. Results are summarized below for individual species and by month. An average of all species is also included.

Hours to Germination

|

|

Month |

|||||

|

Weeds: |

Aug. |

Sept. |

Oct. |

Nov. |

Dec. |

Jan. |

|

Barnyardgrass |

24 |

24 |

48 |

72 |

96 |

NG |

|

Canarygrass |

NG |

168 |

96 |

96 |

96 |

NG |

|

Lambsquarters |

72 |

96 |

96 |

72 |

168 |

NG |

|

Silverleaf Nightshade |

96 |

96 |

72 |

96 |

NG |

NG |

|

Pigweed |

48 |

72 |

48 |

72 |

96 |

NG |

|

Purslane |

24 |

24 |

24 |

48 |

96 |

168 |

|

Shepardspurse |

NG |

NG |

168 |

96 |

168 |

NG |

NG = No germination