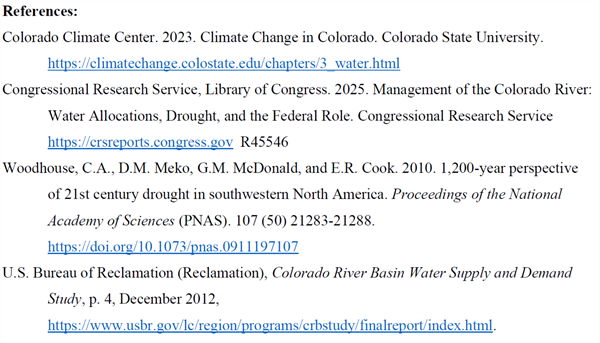

We have now experienced 25 years of significant drought in the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. In the Colorado River basin (Figure 1), the annual flow of the Colorado River has decreased by approximately 19% in the 21st century compared to the 20th century.

From 1906 to 2000, the Colorado River basin averaged about 14.6 million acre-feet (MAF) annually. In the 21st century, average annual flows on the Colorado River have averaged approximately 12.5 MAF per year. This represents a decrease of about 1.75 MAF per year, which is approximately 19% less than the 20th-century average (https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R45546).

This decline is attributed to the change in the climate with warming temperatures and reduced precipitation and is being referred to as a megadrought. The megadrought in the southwestern United States, beginning in 2000, is currently the driest multi-decade period in the region since at least 800 CE. This megadrought has been the driest in at least 1,200 years, exceeding a similar megadrought in the late 1500s. (Woodhouse, et al. 2010).

Long range climate models predict further reductions in Colorado River stream flows, with some projections showing declines of 5% to 30% compared to the 1971-2000 average by 2050 (Colorado Climate Center, 2023).

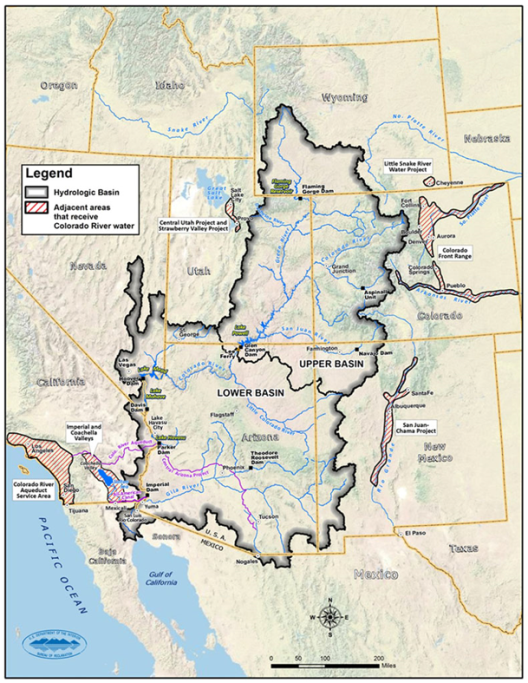

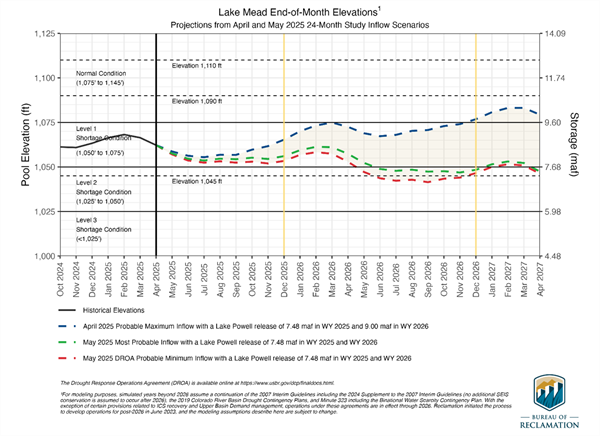

As a result, reservoirs are low throughout the region and the stress on water delivery systems is extreme. Recent projections by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation indicate a high probability of water levels at Lake Mead in December 2026 to be lower than 1,050 ft. above sea level (Figure 2), which would trigger Tier 2a reductions based on the 2007 interim guidelines, Minute 323, lower basin drought contingency plan, and the binational water scarcity contingency plan (Figure 3).

However, all these conservation guidelines on the Colorado River will expire in 2026. Therefore, there is still the need for the delegations representing the Colorado River basin states to develop an agreement on a new set of conservation guidelines. At present, the lower basin states are in agreement, but the upper basin states will not accept the terms proposed by the lower basin states. Thus, they remain at an impasse.

Based on the Law of the River (The Law of the River: Foundational Documents and Programs, CRS, 2025), if the basin states are not able to decide on a new plan together, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DoI) and the Bureau of Reclamation (BoR) will have the responsibility for making the decisions.

At present, a new commissioner for the BoR has not been appointed by the new federal administration. However, based on my understanding from recent basin state meetings, the BoR has been more engaged under the Trump administration and that should be helpful. Stong leadership on these issues is urgently needed, and the situation is presenting a serious test on our system of governance on the Colorado River.

Figure 1. The Colorado River basin and U.S. areas that import Colorado River water.

Source: Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study,

2012.

Figure 2. Lake Mead end-of-month elevations based on model projections from April and

May 2025, 24-Month study inflow scenarios.

Figure 3. Tier 2a reductions based on the 2007 interim guidelines, Minute 323, lower

basin drought contingency plan, and binational water scarcity contingency plan.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

At events and in the halls of the Yuma Agricultural Center, I’ve been hearing murmurings predicting a wet winter this year…

As the Yuma Sun reported last week, “The storms of Monday, Aug. 25 [2025], were the severest conditions of monsoon season so far this year in Yuma County, bringing record-rainfall, widespread power outages and--in the fields--disruptions in planting schedules.”

While the Climate Prediction Center of the National Weather Service maintains its prediction of below average rainfall this fall and winter as a whole, the NWS is saying this week will bring several chances of scattered storms.

These unusually wet conditions at germination can favor seedling disease development. Please be on the lookout for seedling disease in all crops as we begin the fall planting season. Most often the many fungal and oomycete pathogens that cause seedling disease strike before or soon after seedlings emerge, causing what we call damping-off. These common soilborne diseases can quickly kill germinating seeds and young plants and leave stands looking patchy or empty. Early symptoms include poor germination, water-soaked or severely discolored lesions near the soil line, and sudden seedling collapse followed by desiccation.

It is important to note that oomycete and fungal pathogens typically cannot be controlled by the same fungicidal mode of action. That is why an accurate diagnosis is critical before considering treatments with fungicides. If you suspect you have seedling diseases in your field, please submit samples to the Yuma Plant Health Clinic or schedule a field visit with me.

National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/

National Weather Service forecast: https://forecast.weather.govThere are more than 50 broadleaf and grass weeds in this area that are common and have been here for a long time. It would be great to have an herbicide that will control all of them, be safe to the crop and be gone the next day after harvest.

Obviously, we are a long way from achieving this. What we have done instead is select for the weeds that escape our weed control practices. Anything that shifts the advantage to the crop instead of the weeds will help. Our practices include the use of herbicides, mechanical techniques and hand hoeing. Good weed control can be achieved using all three but may not be economical.

Weed selection due to herbicide availability was evident a few years ago when leaf lettuce was removed from the Kerb label in 2009. It is well known that Kerb, Prefar and Balan were the standard herbicides used in lettuce for the last 60years. Kerb will control the grasses and most of the broadleaves consistently including many that are not controlled by the other two products such as shepherds purse, london rocket and wild mustard. The longer that Kerb was unavailable the more prevalent some weeds would become. On January 12, 2016, the EPA label for Kerb was reinstated for leaf lettuce bringing back the tool to the industry1.

Prefar will control grass consistently, purslane and pigweed most of the time, lambs quarters and goosefoot some of the time. Balan will control grass consistently and many of the small-seeded broadleaves some of the time.

The postemergence grass herbicides were registered about 30 years ago but for broadleaf weeds there has not been a new registration in half a century.

Reference:

1. Retrieved from the www on Oct 14, 2024 https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=21270#:~:text=On%20January%2012%2C%202016%20the%20Federal%20EPA,55%20day%20prior%20to%20harvest%20(Table%201).

2. https://cales.arizona.edu/crop/vegetables/advisories/more/weed122.html

I had the privilege of knowing John for just over a year, yet his impact on my professional journey has been profound. To me, John was more than a colleague—he was a mentor. The knowledge I acquired from him will shape my career for years to come. His legacy was truly contagious and has inspired me to follow in his footsteps. John’s influence will continue to guide and motivate me throughout my life.

May God bless your soul, John. Rest in peace.Lettuce is one of the most important vegetable crops in the Yuma, Arizona region. However, growing healthy lettuce in the desert isn’t easy. High temperatures, salty soils, and very low rainfall (less than 3 inches per year) make crop management especially difficult. Growers are always looking for better tools to improve crop growth while saving water and reducing input costs.

Biostimulants are one such tool. These are natural products often made from seaweed extracts, organic acids, or beneficial microbes that are added to the soil or irrigation water. They don’t replace fertilizers, but they can help plants grow better by improving how roots absorb nutrients and handle stress like heat, drought, or poor soil quality.

Our Trial in Yuma, AZ

To better understand whether biostimulants can help desert lettuce crops, we conducted a field trial during the 2024–2025 growing season at the University of Arizona’s Valley

Research Center in Yuma. The field was managed using subsurface drip irrigation, a water-saving system that delivers moisture directly to the plant roots below the soil surface. We tested a commercially available biostimulant made from organic compounds and micronutrients known to support root and shoot growth.

The trial included several treatments, some with biostimulant and some without, under both traditional and sensor-based irrigation scheduling. We tracked plant height every two weeks to monitor lettuce growth and compared results between the treated and untreated plots.

What We Found

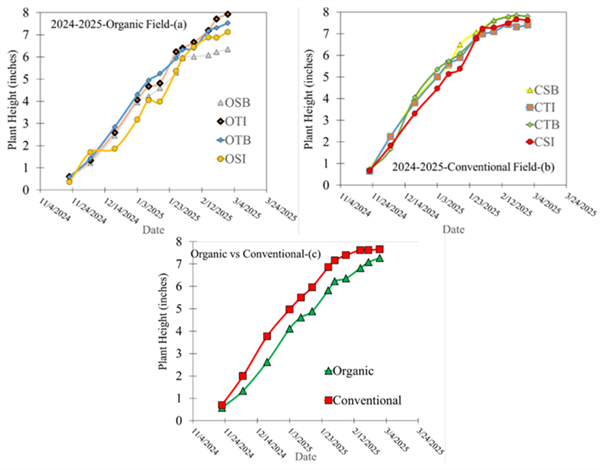

In the organic lettuce trial, biostimulant use did not result in a clear or measurable increase in plant height. All treatments (Figure 1), whether biostimulant was applied or not, showed similar growth patterns and reached comparable final heights by the end of the season. In the conventional lettuce trial, the tallest plants appeared in the biostimulant-treated plots; however, the difference compared to untreated plots was small and not statistically significant. When the data from both systems were combined, conventional treatments consistently produced taller plants than organic ones, regardless of biostimulant application. These findings suggest that biostimulant effects on plant height are minimal and highly dependent on the production system and environmental or management factors.

Takeaway

Biostimulants may not be a magic solution for crop growth and development, but they offer promise as part of an integrated crop management strategy. In desert systems where water is limited and soils can be harsh, even modest improvements in plant growth can help growers increase their productivity and resilience.

Figure 1. Distribution of plant height: (a) Organic Field; Organic sensor-based irrigation +

biostimulant (OSB), Organic traditional-based irrigation (OTI), Organic traditional-based

irrigation + biostimulant (OTB), and Organic sensor-based irrigation (OSI); (b)

Conventional Field; Conventional sensor-based irrigation + biostimulant (CSB),

Conventional traditional-based irrigation (CTI), Conventional traditional-based irrigation +

biostimulant (CTB), and Conventional sensor-based irrigation (CSI); (c) Pooled data for

Organic and Conventional Field treatments. Each data point represents the average of

10 readings collected in the field at the Valley Research Center, University of Arizona,

Yuma Agricultural Center, Yuma, Arizona.

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches can be viewed here.

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts down in most over the last month, but increased activity in Wellton and Tacna in the past week; above average for this time of season.

Beet armyworm: Moth trap counts increased in most areas, above average for this time of the year.

Cabbage looper: Moths remain in all traps in the past 2 weeks, and average for this time of the season.

Diamondback moth: Adults decreased to all locations but still remain active in Wellton and the N. Yuma Valley. Overall, below average for January.

Whitefly: Adult movement remains low in all areas, consistent with previous years.

Thrips: Thrips adults movement decreased in past 2 weeks, overall activity below average for January.

Aphids: Winged aphids are still actively moving, but lower in most areas. About average for January.

Leafminers: Adult activity down in most locations, below average for this time of season.