Following the recent Russian invasion, many aspects of Ukraine have been reviewed. Ukraine is often referenced to Kansas and that section of American Great Plains and I remember this comparison being made when I was an agronomy student at Kansas State University in the early 1970s. The agricultural importance of Ukraine was impressed upon us as agronomy students then and it is important today as well. However, colleagues of mine who are from Ukraine and some who have visited there say that Indiana is probably a better comparison in terms of landscapes and agroecosystems.

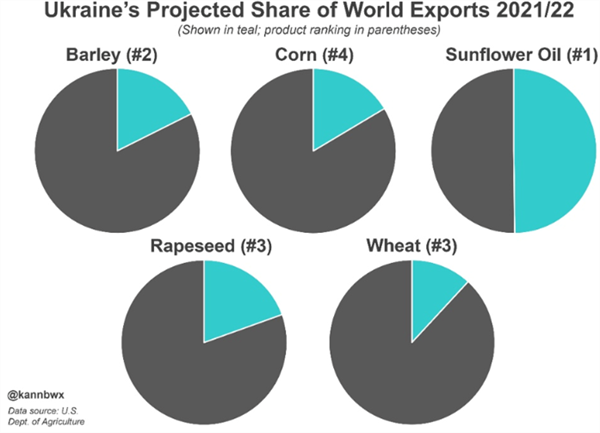

Agriculture is a very important part of Ukrainian history and for many centuries, Ukraine has been considered as the “breadbasket of Europe”, similar to the Great Plains of North America. In 2020, Ukraine's agriculture sector generated approximately 9.3% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Crop farming, which accounts for 73% of agricultural output, dominates Ukrainian agriculture, according to the International Trade Administration. The country's main crops are sunflowers, corn, soybeans, wheat, and barley. In terms of global exports, Ukraine produces 18% of the world's sunflower seed, safflower, or cottonseed oil exports; 13% of corn production; 12% of global barley exports; and 8% of wheat and meslin (a combination of wheat and rye).

Grain exports are a very important part of Ukraine’s economy. It has been projected that this year Ukraine was poised to export more than three-fourths of its domestic corn and wheat crop. That compares with one-fifth for the United States. Oilseed exports have become increasingly important for Ukraine accounting for half of the world’s sunflower oil exports and is the No. 3 international rapeseed exporter. Many global oilseeds, particularly vegetable oils, have hit record-high prices within the last year and the Ukrainian situation may exacerbate that.

This year, Ukraine has been predicted to account for 12% of global wheat exports, 16% for corn, 18% for barley and 19% for rapeseed, (FAO and Statistics of Ukraine). It is interesting to note that cotton production has been resumed in parts of southern Ukraine in recent years, but it is extremely small in terms planted area and productivity.

Figure 1. Ukraine’s projected share of world exports, 2021-2022.

The weather in Ukraine is suitable for both winter and spring crops. Average annual precipitation in Ukraine is approximately 600 mm (24 inches). Ukraine receives approximately 350 mm (14 inches) of precipitation during the growing season (April through October). Rainfall amounts are typically higher in western and central Ukraine and lower in the south and east. The agricultural areas of Ukraine are located at ~ 48° N (Figure 2).

The total area of Ukraine is over 60M ha (148M acres) with about 42M ha (104M acres) under agricultural production. Crop production systems in Ukraine include field crop cultivation, grass farming, vegetables, fruits, and nuts. Sunflowers and sugar beets are the main technical or industrial, crops. Grain production, particularly winter wheat, is extremely important in the field crop production systems of Ukraine. Other crops include fodder, vegetable, melon, and potato crops. Grain crops represent 46.6% of total Ukrainian crop production; industrial crops 11.7%; potato, vegetables, melon, and gourd, 6.6%; and fodder or forage crops, 35.1%. In the past, Ukrainian grain production has reached 35-45M t/year. The major grain crops are corn, winter wheat, followed by barley, maize, rye, and oats. Leguminous plants of high protein content include peas, beans, fodder lupin, soybeans, and forage crops, (FAO and Statistics of Ukraine).

Ukraine has played a major role in economic and political developments in the region. Ukraine was one of the naturally richest parts of the Soviet Union and Ukraine served as a major “breadbasket” for the massive superpower, producing large amounts of small grains and corn for distribution domestically and abroad. Being such a large producer of food, Ukraine was a prime target for collectivization under Stalin and possession of the region was the cause for tension between Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany during WWII. Stalin imposed a program of food and crop removal in 1932-1933 from Ukrainian farmers that created a horrible famine and genocide known as the “Holodomor” that killed approximately 10M Ukrainians. Ukraine had the largest population and the highest level of economic development of all the agricultural areas that were collectivized under Stalin.

Former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who led the Soviet Union from 1958 to 1964, maintained a close relationship with Ukraine. His hometown, Kalinovka, was located seven miles from the Russian border with Ukraine, and he spent much of his life working in the Donbas region in the eastern part of the country. After World War II, he was appointed Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine and played a pivotal role in rebuilding Kyiv, which had been heavily bombed by the Germans. (Clark, 2014).

Agriculture in Ukraine has been changing and evolving since independence from the Soviet Union was achieved in 1991, following the Soviet Union breakup. This has been a challenge in all of the former Soviet Union republics in the past 30 years and Ukraine has generally done well or better than most. State and collective farms were officially dismantled in 2000. Farm property was divided among the farm workers in the form of land shares and most new shareholders leased their land back to recently formed private agricultural associations, (International Trade Administration and Statistics of Ukraine). Recently, Ukraine has produced enough food to feed 400 million people in addition to its own population of 44 million. Ukraine has experienced a nearly 10X increase in food exports over the past 20 years with more than 40% of Ukraine’s annual corn and wheat shipments have been directed to the Middle East or Africa.

This is only a very brief review of Ukrainian agriculture. For those of us working in agriculture, the Ukrainian agricultural capacity is good for us to understand in relation to what is transpiring today in that nation and the impacts that may have on global markets.

Figure 2. Environmental zones of Ukraine.

References:

Clark, Trevor L., "Changes in the Portrayal of Ukrainian Agriculture 1949-1966." (2014). EKU Libraries Research Award for Undergraduates. 13. http://encompass.eku.edu/ugra/2014/2014/13

Food and Agricultural Association (FAO), United Nations, Rome, Italy. Ukraine Agriculture. 2012. https://www.fao.org/3/y2722e/y2722e17.htm

International Trade Administration – U.S. Government. https://www.usa.gov/federal-agencies/international-trade-administration

Statistics of Ukraine. 2009. Agriculture of Ukraine. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Derzhanalitinform. Kyiv. 361 pp. [in Ukrainian].

I hope you are frolicking in the fields of wildflowers picking the prettiest bugs.

I was scheduled to interview for plant pathologist position at Yuma on October 18, 2019. Few weeks before that date, I emailed Dr. Palumbo asking about the agriculture system in Yuma and what will be expected of me. He sent me every information that one can think of, which at the time I thought oh how nice!

When I started the position here and saw how much he does and how much busy he stays, I was eternally grateful of the time he took to provide me all the information, especially to someone he did not know at all.

Fast forward to first month at my job someone told me that the community wants me to be the Palumbo of Plant Pathology and I remember thinking what a big thing to ask..

He was my next-door mentor, and I would stop by with questions all the time especially after passing of my predecessor Dr. Matheron. Dr. Palumbo was always there to answer any question, gave me that little boost I needed, a little courage to write that email I needed to write, a rigid answer to stand my ground if needed. And not to mention the plant diagnosis. When the submitted samples did not look like a pathogen, taking samples to his office where he would look for insects with his little handheld lenses was one of my favorite times.

I also got to work with him in couple of projects, and he would tell me “call me John”. Uhh no, that was never going to happen.. until my last interaction with him, I would fluster when I talked to him, I would get nervous to have one of my idols listening to ME? Most times, I would forget what I was going to ask but at the same time be incredibly flabbergasted by the fact that I get to work next to this legend of a man, and get his opinions about pest management. Though I really did not like giving talks after him, as honestly, I would have nothing to offer after he has talked. Every time he waved at me in a meeting, I would blush and keep smiling for minutes, and I always knew I will forever be a fangirl..

Until we meet again.

Mark C. Siemens Vol. 12, Issue 20, Published 10/06/2021 Plans are shaping up for the 2nd Automated Weeding Technologies Field Demo Day. The event will be held Thursday, October 21st at the Yuma Agricultural Center. Registration begins at 7:00 am and the program starts at 7:30 am. We have eight presentations/field demos scheduled (details below). The focus this year is on the latest automated weeding technologies that are “new” since our 2018 event. We would love to showcase as many innovations as possible and it’s not too late to be added to the program. It’s an open invitation - private companies, university and government researchers are all welcome to show their technology. Please contact me if you are interested or know someone that is.

Clovers can be very difficult to control weeds here, but it is also a major crop and common ornamental. Clovers can survive under poor growing conditions and are not controlled with glyphosate and seem to get worse every year. There are more than 50 types and 300 species of clover and they can be easily misidentified. They are all in the legume (Fabracea) family and can use a bacterium (rhizobium) in the soil to convert nitrogen in the atmosphere to a form that they and other plants can use for fertilizer. There are only 4 or 5 clover species that are agricultural pests here. The ones we get the most questions on are white and yellow sweet clover. These are in the Melilotus family. White sweet clover (Melilotus albus) is tall for a clover and can get 3 to 5 foot in height. The leaves are thinner than most clovers and this difficult to control weed lives at least 2 years and sometimes longer. Glyphosate and most of the contact herbicides do not control it. The plant growth regulator herbicides work best. Yellow sweet clover (Melilotus officinalis) is less common here. The flowers are yellow, and it is not as tall and vegetative as white sweet clover. Yellow is more common at higher elevations. California burclover (Medicago polymorpha) and Black medic (Medicago lupina) are in the same genus as alfalfa and are more of a problem in landscapes, parks and golf courses than in agricultural fields here. They do not grow upright and spread below the crop or turf. The true clovers are in the Trifolium genus and include white and strawberry clover. These creep along the ground and root at the nodes of the stem. These are more of a urban landscape weed and not considered an agricultural problem. Creeping woodsorrel or Oxyalis looks like a clover but it is not related. It is a turf weed that spreads rapidly along the ground and can live for several years. Preemergent herbicides are effective against all these clovers before they become established. The postemergence herbicides that are most effective in controlling these clovers are the plant growth regulators. Contact herbicides and glyphosate are generally ineffective.