Following the recent Russian invasion, many aspects of Ukraine have been reviewed. Ukraine is often referenced to Kansas and that section of American Great Plains and I remember this comparison being made when I was an agronomy student at Kansas State University in the early 1970s. The agricultural importance of Ukraine was impressed upon us as agronomy students then and it is important today as well. However, colleagues of mine who are from Ukraine and some who have visited there say that Indiana is probably a better comparison in terms of landscapes and agroecosystems.

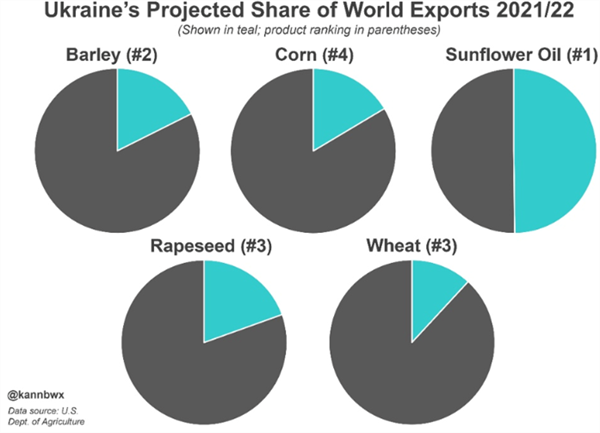

Agriculture is a very important part of Ukrainian history and for many centuries, Ukraine has been considered as the “breadbasket of Europe”, similar to the Great Plains of North America. In 2020, Ukraine's agriculture sector generated approximately 9.3% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Crop farming, which accounts for 73% of agricultural output, dominates Ukrainian agriculture, according to the International Trade Administration. The country's main crops are sunflowers, corn, soybeans, wheat, and barley. In terms of global exports, Ukraine produces 18% of the world's sunflower seed, safflower, or cottonseed oil exports; 13% of corn production; 12% of global barley exports; and 8% of wheat and meslin (a combination of wheat and rye).

Grain exports are a very important part of Ukraine’s economy. It has been projected that this year Ukraine was poised to export more than three-fourths of its domestic corn and wheat crop. That compares with one-fifth for the United States. Oilseed exports have become increasingly important for Ukraine accounting for half of the world’s sunflower oil exports and is the No. 3 international rapeseed exporter. Many global oilseeds, particularly vegetable oils, have hit record-high prices within the last year and the Ukrainian situation may exacerbate that.

This year, Ukraine has been predicted to account for 12% of global wheat exports, 16% for corn, 18% for barley and 19% for rapeseed, (FAO and Statistics of Ukraine). It is interesting to note that cotton production has been resumed in parts of southern Ukraine in recent years, but it is extremely small in terms planted area and productivity.

Figure 1. Ukraine’s projected share of world exports, 2021-2022.

The weather in Ukraine is suitable for both winter and spring crops. Average annual precipitation in Ukraine is approximately 600 mm (24 inches). Ukraine receives approximately 350 mm (14 inches) of precipitation during the growing season (April through October). Rainfall amounts are typically higher in western and central Ukraine and lower in the south and east. The agricultural areas of Ukraine are located at ~ 48° N (Figure 2).

The total area of Ukraine is over 60M ha (148M acres) with about 42M ha (104M acres) under agricultural production. Crop production systems in Ukraine include field crop cultivation, grass farming, vegetables, fruits, and nuts. Sunflowers and sugar beets are the main technical or industrial, crops. Grain production, particularly winter wheat, is extremely important in the field crop production systems of Ukraine. Other crops include fodder, vegetable, melon, and potato crops. Grain crops represent 46.6% of total Ukrainian crop production; industrial crops 11.7%; potato, vegetables, melon, and gourd, 6.6%; and fodder or forage crops, 35.1%. In the past, Ukrainian grain production has reached 35-45M t/year. The major grain crops are corn, winter wheat, followed by barley, maize, rye, and oats. Leguminous plants of high protein content include peas, beans, fodder lupin, soybeans, and forage crops, (FAO and Statistics of Ukraine).

Ukraine has played a major role in economic and political developments in the region. Ukraine was one of the naturally richest parts of the Soviet Union and Ukraine served as a major “breadbasket” for the massive superpower, producing large amounts of small grains and corn for distribution domestically and abroad. Being such a large producer of food, Ukraine was a prime target for collectivization under Stalin and possession of the region was the cause for tension between Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany during WWII. Stalin imposed a program of food and crop removal in 1932-1933 from Ukrainian farmers that created a horrible famine and genocide known as the “Holodomor” that killed approximately 10M Ukrainians. Ukraine had the largest population and the highest level of economic development of all the agricultural areas that were collectivized under Stalin.

Former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who led the Soviet Union from 1958 to 1964, maintained a close relationship with Ukraine. His hometown, Kalinovka, was located seven miles from the Russian border with Ukraine, and he spent much of his life working in the Donbas region in the eastern part of the country. After World War II, he was appointed Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine and played a pivotal role in rebuilding Kyiv, which had been heavily bombed by the Germans. (Clark, 2014).

Agriculture in Ukraine has been changing and evolving since independence from the Soviet Union was achieved in 1991, following the Soviet Union breakup. This has been a challenge in all of the former Soviet Union republics in the past 30 years and Ukraine has generally done well or better than most. State and collective farms were officially dismantled in 2000. Farm property was divided among the farm workers in the form of land shares and most new shareholders leased their land back to recently formed private agricultural associations, (International Trade Administration and Statistics of Ukraine). Recently, Ukraine has produced enough food to feed 400 million people in addition to its own population of 44 million. Ukraine has experienced a nearly 10X increase in food exports over the past 20 years with more than 40% of Ukraine’s annual corn and wheat shipments have been directed to the Middle East or Africa.

This is only a very brief review of Ukrainian agriculture. For those of us working in agriculture, the Ukrainian agricultural capacity is good for us to understand in relation to what is transpiring today in that nation and the impacts that may have on global markets.

Figure 2. Environmental zones of Ukraine.

References:

Clark, Trevor L., "Changes in the Portrayal of Ukrainian Agriculture 1949-1966." (2014). EKU Libraries Research Award for Undergraduates. 13. http://encompass.eku.edu/ugra/2014/2014/13

Food and Agricultural Association (FAO), United Nations, Rome, Italy. Ukraine Agriculture. 2012. https://www.fao.org/3/y2722e/y2722e17.htm

International Trade Administration – U.S. Government. https://www.usa.gov/federal-agencies/international-trade-administration

Statistics of Ukraine. 2009. Agriculture of Ukraine. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Derzhanalitinform. Kyiv. 361 pp. [in Ukrainian].

Hi, I’m Chris, and I’m thrilled to be stepping into the role of extension associate for plant pathology through The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension in Yuma County. I recently earned my Ph.D. in plant pathology from Purdue University in Indiana where my research focused on soybean seedling disease caused by Fusarium and Pythium. There, I discovered and characterized some of the first genetic resources available for improving innate host resistance and genetic control to two major pathogens causing this disease in soybean across the Midwest.

I was originally born and raised in Phoenix, so coming back to Arizona and getting the chance to apply my education while helping the community I was shaped by is a dream come true. I have a passion for plant disease research, especially when it comes to exploring how plant-pathogen interactions and genetics can be used to develop practical, empirically based disease control strategies. Let’s face it, fungicide resistance continues to emerge, yesterday’s resistant varieties grow more vulnerable every season, and the battle against plant pathogens in our fields is ongoing. But I firmly believe that when the enemy evolves, so can we.

To that end I am proud to be establishing my research program in Yuma where I will remain dedicated to improving the agricultural community’s disease management options and tackling crop health challenges. I am based out of the Yuma Agricultural Center and will continue to run the plant health diagnostic clinic located there.

Please drop off or send disease samples for diagnosis to:

Yuma Plant Health Clinic

6425 W 8th Street

Yuma, AZ 85364

If you are shipping samples, please remember to include the USDA APHIS permit for moving plant samples.

You can contact me at:

Email: cdetranaltes@arizona.edu

Cell: 602-689-7328

Office: 928-782-5879

Mark C. Siemens Vol. 12, Issue 20, Published 10/06/2021 Plans are shaping up for the 2nd Automated Weeding Technologies Field Demo Day. The event will be held Thursday, October 21st at the Yuma Agricultural Center. Registration begins at 7:00 am and the program starts at 7:30 am. We have eight presentations/field demos scheduled (details below). The focus this year is on the latest automated weeding technologies that are “new” since our 2018 event. We would love to showcase as many innovations as possible and it’s not too late to be added to the program. It’s an open invitation - private companies, university and government researchers are all welcome to show their technology. Please contact me if you are interested or know someone that is.

Clovers can be very difficult to control weeds here, but it is also a major crop and common ornamental. Clovers can survive under poor growing conditions and are not controlled with glyphosate and seem to get worse every year. There are more than 50 types and 300 species of clover and they can be easily misidentified. They are all in the legume (Fabracea) family and can use a bacterium (rhizobium) in the soil to convert nitrogen in the atmosphere to a form that they and other plants can use for fertilizer. There are only 4 or 5 clover species that are agricultural pests here. The ones we get the most questions on are white and yellow sweet clover. These are in the Melilotus family. White sweet clover (Melilotus albus) is tall for a clover and can get 3 to 5 foot in height. The leaves are thinner than most clovers and this difficult to control weed lives at least 2 years and sometimes longer. Glyphosate and most of the contact herbicides do not control it. The plant growth regulator herbicides work best. Yellow sweet clover (Melilotus officinalis) is less common here. The flowers are yellow, and it is not as tall and vegetative as white sweet clover. Yellow is more common at higher elevations. California burclover (Medicago polymorpha) and Black medic (Medicago lupina) are in the same genus as alfalfa and are more of a problem in landscapes, parks and golf courses than in agricultural fields here. They do not grow upright and spread below the crop or turf. The true clovers are in the Trifolium genus and include white and strawberry clover. These creep along the ground and root at the nodes of the stem. These are more of a urban landscape weed and not considered an agricultural problem. Creeping woodsorrel or Oxyalis looks like a clover but it is not related. It is a turf weed that spreads rapidly along the ground and can live for several years. Preemergent herbicides are effective against all these clovers before they become established. The postemergence herbicides that are most effective in controlling these clovers are the plant growth regulators. Contact herbicides and glyphosate are generally ineffective.

This time of year, John would often highlight Lepidopteran pests in the field and remind us of the importance of rotating insecticide modes of action. With worm pressure present in local crops, it’s a good time to revisit resistance management practices and ensure we’re protecting the effectiveness of these tools for seasons to come. For detailed guidelines, see Insecticide Resistance Management for Beet Armyworm, Cabbage Looper, and Diamondback Moth in Desert Produce Crops .

VegIPM Update Vol. 16, Num. 20

Oct. 1, 2025

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches below!!

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts declined across all traps from last collection; average for this time of year.

Beet armyworm: BAW moth increased over the last two weeks; below average for this early produce season.

Cabbage looper: Cabbage looper counts increased in the last two collections; below average for mid-late September.

Diamondback moth: a few DBM moths were caught in the traps; consistent with previous years.

Whitefly: Adult movement decreased in most locations over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.

Thrips: Thrips adult activity increased over the last two collections, typical for late September.

Aphids: Aphid movement absent so far; anticipate activity to pick up when winds begin blowing from N-NW.

Leafminers: Adult activity increased over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.