Water is the first limiting factor in desert crop production systems, followed closely by bio-available nitrogen (N). Nitrogen fertilizer application rates for desert vegetable crops typically range from ~ 150-300 lbs. N/acre. This variation can be due to a lot of factors, including the residual soil N levels, crop rotations, length of the production cycle for the crop, etc.

Due to the critical nature of N availability for the growth of a healthy and marketable crop with good yields in a timely manner, growers are alert to preventing a N deficiency in desert vegetable crop production. Prices for fertilizer N are always a major factor in the crop production budget for any field and that is certainly turning out to be an important issue this year with higher fertilizer N prices.

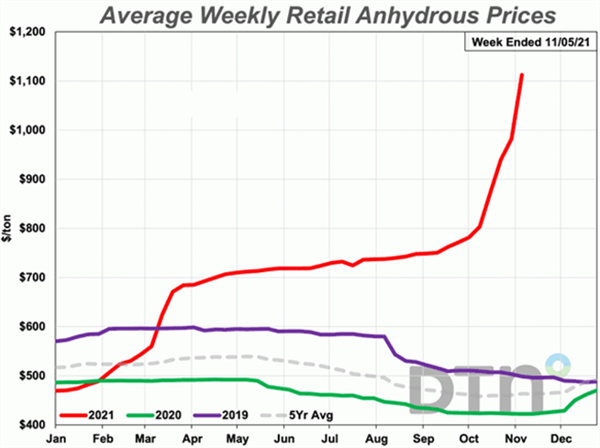

Figure 1 shows the average North American fertilizer price gauge pattern from 2007-2021 with a distinct surge in 2021. This surge in fertilizer prices is reminiscent of a similar pattern in 2008 and quite an increase in relation to average prices experienced in the past five years. More specific to N fertilizer costs, Figure 2 shows the average weekly retail anhydrous prices in the U.S. 2019-2021 with a five-year average.

The primary driving force in a higher average North American fertilizer price gauge is associated with N fertilizers. Anhydrous ammonia is a good gauge for overall N fertilizer price since so many N fertilizers utilize anhydrous ammonia in the manufacturing process. Nitrogen fertilizer price increases are being driven by the following major factors:

Collectively, this all translates to a more costly and perhaps challenging year for nutrient management in desert vegetable production systems. These challenges can be dealt with by consideration of the 4R approach to plant nutrient application, consisting of:

1. Right fertilizer source at the

2. Right rate, at the

3. Right time and in the

4. Right place

The 4R nutrient stewardship approach utilizes the implementation of best management practices (BMPs) that optimize the fertilizer use efficiency by the crop. The primary objective of the 4R approach and BMPs is to match nutrient supply with crop requirements and to minimize nutrient losses from fields. With higher fertilizer prices, this can be more important in crop production management for this year.

Figure 1. North American fertilizer prices.

Figure 1. North American fertilizer prices.

Figure 2. Average weekly retail anhydrous prices. Source: Progressive Farmer, 10 November 2021.

Hi, I’m Chris, and I’m thrilled to be stepping into the role of extension associate for plant pathology through The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension in Yuma County. I recently earned my Ph.D. in plant pathology from Purdue University in Indiana where my research focused on soybean seedling disease caused by Fusarium and Pythium. There, I discovered and characterized some of the first genetic resources available for improving innate host resistance and genetic control to two major pathogens causing this disease in soybean across the Midwest.

I was originally born and raised in Phoenix, so coming back to Arizona and getting the chance to apply my education while helping the community I was shaped by is a dream come true. I have a passion for plant disease research, especially when it comes to exploring how plant-pathogen interactions and genetics can be used to develop practical, empirically based disease control strategies. Let’s face it, fungicide resistance continues to emerge, yesterday’s resistant varieties grow more vulnerable every season, and the battle against plant pathogens in our fields is ongoing. But I firmly believe that when the enemy evolves, so can we.

To that end I am proud to be establishing my research program in Yuma where I will remain dedicated to improving the agricultural community’s disease management options and tackling crop health challenges. I am based out of the Yuma Agricultural Center and will continue to run the plant health diagnostic clinic located there.

Please drop off or send disease samples for diagnosis to:

Yuma Plant Health Clinic

6425 W 8th Street

Yuma, AZ 85364

If you are shipping samples, please remember to include the USDA APHIS permit for moving plant samples.

You can contact me at:

Email: cdetranaltes@arizona.edu

Cell: 602-689-7328

Office: 928-782-5879

In several previous articles (Vol. 11 (13), Vol. 11 (20), Vol. 11 (24), Vol. 12 (5), Vol 12 (12)), I’ve discussed using band-steam to control pests. Band-steam is where steam is used to heat narrow strips of soil to levels sufficient to kill soilborne pathogens and weeds (>140 °F for > 20 minutes). The concept has shown promise (see previous articles) and we are continuing to examine the technique to confirm previous results and assess its efficacy for controlling additional pests.

Over the course of the last several weeks, we established five trials, two in in Yuma, AZ and three in Salinas, CA. In Yuma, AZ, we are assessing control of weeds and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Lactucae, the pathogen which causes Fusarium wilt of lettuce in romaine and iceberg lettuce. In Salinas, CA, we are examining control of weeds and cavity spot (Pythium spp.) in carrot, lettuce drop (Sclerotinia spp.) in romaine lettuce, and fusarium wilt of lettuce in iceberg lettuce (Fig.1).

Consistent with previous studies, early results from Yuma, AZ are showing treatment with steam heat is effective at controlling weeds (Fig. 2). Stay tuned for final trial results.

The band-steam applicator will be back in Yuma, AZ this fall for additional testing. If you are interested in evaluating band-steam on your farm, please contact me. We are seeking additional sites, particularly those with a known history of Fusarium wilt of lettuce disease incidence to test the efficacy and performance of the device.

As always, if you are interested in seeing the machine operate or would like more information, please feel free to contact me.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Crop Protection and Pest Management grant no. 2017-70006-27273/project accession no. 1014065 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the Arizona Specialty Crop Block Grant Program, and the Arizona Iceberg Lettuce Research Council. We greatly appreciate their support. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A special thank you is extended to Christensen & Giannini, LLC for allowing us to conduct research trials on their farm.

Fig. 1. Establishing band-steam trials in Salinas, CA to determine the efficacy of

using steam heat for controlling weeds and fusarium wilt of lettuce.

Fig. 2. Band-steam and untreated plots planted to lettuce (12 days after planting).

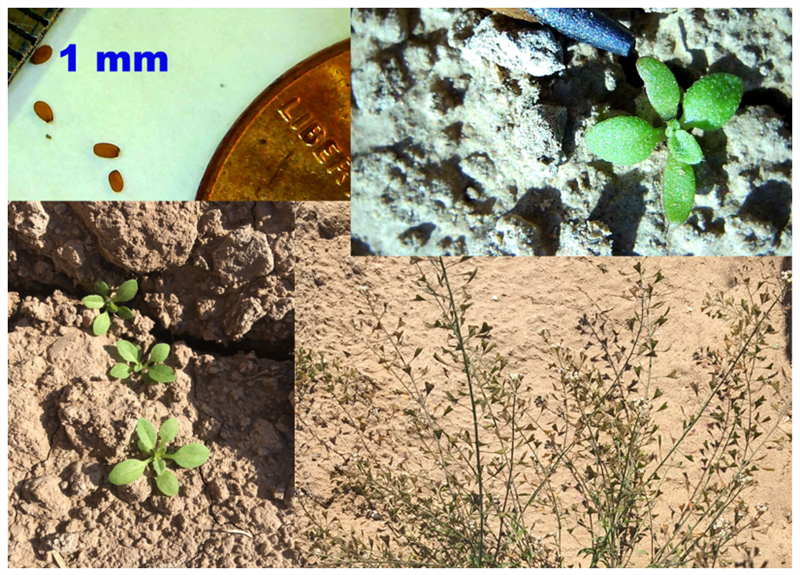

Although it is not vigorous or vegetative, Shepardspurse is one of the most widespread and difficult to control broadleaf weeds worldwide. I used to think that it spread when there was more alfalfa here and because it is not controlled with 2,4-DB (Butyrate & Butoxone) but it has continued to spread in vegetable crops. It likely has become worse each year because of its growth habits more than its tolerance to herbicides. It germinates from on or just below the soil surface. Herbicides that move or are placed below the surface often miss it. It is difficult to control with Kerb, for instance, because it leaches easily with overhead sprinklers. The seed is less than 0.1 inch in diameter and moves easily in wind and water. It is very small, and the cotyledon leaves are hardly ever seen. By the time you see it, it is at the 3 or 4 leaf stage. It grows rapidly in a rosette that is low to the ground and often covered by the crop. Herbicide coverage is difficult. It soon puts up a thin seed stalk and several seed pods (“purses”). Unlike many annual broadleaf weeds, it can produce several generations in one season. It can grow year round in many regions but has a difficult time surviving the summers in the low desert.

This time of year, John would often highlight Lepidopteran pests in the field and remind us of the importance of rotating insecticide modes of action. With worm pressure present in local crops, it’s a good time to revisit resistance management practices and ensure we’re protecting the effectiveness of these tools for seasons to come. For detailed guidelines, see Insecticide Resistance Management for Beet Armyworm, Cabbage Looper, and Diamondback Moth in Desert Produce Crops .

VegIPM Update Vol. 16, Num. 20

Oct. 1, 2025

Results of pheromone and sticky trap catches below!!

Corn earworm: CEW moth counts declined across all traps from last collection; average for this time of year.

Beet armyworm: BAW moth increased over the last two weeks; below average for this early produce season.

Cabbage looper: Cabbage looper counts increased in the last two collections; below average for mid-late September.

Diamondback moth: a few DBM moths were caught in the traps; consistent with previous years.

Whitefly: Adult movement decreased in most locations over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.

Thrips: Thrips adult activity increased over the last two collections, typical for late September.

Aphids: Aphid movement absent so far; anticipate activity to pick up when winds begin blowing from N-NW.

Leafminers: Adult activity increased over the last two weeks, about average for this time of year.