https://uarizona.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_cMhZ82JodDKJgCa

Shaku Nair, Dawn H. Gouge, Shujuan Li

Department of Entomology, University of Arizona

Ants are some of the most common insects found in community environments. They thrive indoors and outdoors, wherever they have access to food and water. In general, ants are considered nuisance pests and will not cause significant damage if managed in a timely manner. Ants outdoors are mostly beneficial, as they serve as scavengers and decomposers of organic matter, predators of small insects and seed dispersers of certain plants. However, some ant species (e.g., fire ants) can inflict painful bites and stings, and this is a cause for concern. Others (e.g., carpenter ants) can cause damage to wooden structures by hollowing out wood. Of late, leaf cutter ants have been reported as a problem in many areas, stripping landscape and garden plants of their leaves.

Ant identification

The body of an ant can be divided into three distinct regions: head, thorax, and abdomen which consists of the narrow constriction (waist or petiole) and the part beyond it (gaster) (Figure 1). The waist can be made up of one or two small segments (nodes) and this is an important preliminary identifying feature, based on which ants are broadly grouped as one-node and two-node ants.

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of differences between one-node and two-node ants.

Source: USDA-ARS.

However, ants are small insects and these characters are often difficult to identify with the naked eye. Some of the largest species in Arizona (carpenter and harvester ants) are only about 1/2 inch in length, while individuals of smaller species range in length from ⅛ to ¼ of an inch. Many species are polymorphic, meaning that individuals of the same species can vary greatly in appearance. Therefore, an understanding of behavioral aspects (nesting, trailing and food preferences, etc.) of some of the common species can be helpful in their identification and management.

Important Two-Node Ant Species

Fire Ants

Fire ants are one of the most common ant species of concern. There are many known species of fire ants (Solenopsis spp.) in the United States, at least three of which are commonly found in Arizona: the native southern fire ant (Solenopsis xyloni), and two species of desert fire ants (Solenopsis aurea and Solenopsis amblychila). The red imported fire ant (RIFA, Solenopsis invicta) is not established in Arizona, but is found in the southern areas of New Mexico and California. The arid climate in the low desert area is a limiting factor for this invasive species.

Southern fire ants, Solenopsis xyloni are the most common species of fire ants found in Arizona and are native to the southwest. The adults have a dark reddish-brown colored head and thorax, with darker brown or black abdomen (Figure 2). The body is covered with golden hairs. The waist has two erect nodes. Fire ant workers are polymorphic, meaning they vary in size from 1/8 inch to over 1/4 inch in length, but queens are larger. The ants are active in the morning and early evening.

Figure 2. Southern fire ant worker. Photo: Eli Sarnat,

Fire ants feed on different food materials including human food but have a preference for sweets and proteins. Candy bars and other nut-containing sweets are among their favorites

Some landscape practices, such as leaving turf or landscape areas bare or compacted, mowing too close to the soil, or edging turf too low with a strimmer, generate ideal conditions for southern fire ants to thrive.

Fire ants are notorious stinging and biting pests in most community environments. They build unDsightly mounds in different indoor and outdoor locations, mostly near a source of moisture. The mounds do not have a characteristic shape, but rather look like piles of dirt (Figure 3). This makes them difficult to recognize in a landscape. When disturbed, workers pour out of the mounds in large numbers and inflict painful bites and stings on the intruder. These ants do not form regular trails, but move in random paths. Although they are less aggressive than the closely related species S. invicta (Red Imported Fire Ants) and their stings and bites are less intense, people vary in their sensitivity to fire ant venom and so the presence of fire ants should be given due importance and attention.

Figure 3. Southern fire ant mound. Photo: Shaku Nair.

Be aware of fire ant activity in your surroundings, and keep children, pets, and people with sensitivity to fire ant venom away from their mounds. Teach children about fire ant hazards, and inform visitors to your landscape, if fire ants are present.

******************************************************************************************************************************

Our concise trifold publication “Beware of Fire Ant Stings”, covers more information about fire ants including how to avoid their stings, and what to do if you are stung. View or download the publication at this link: https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1954-2021.pdf

******************************************************************************************************************************

Western Harvester ants Pogonomyrmex occidentalis, are another large species of ants, native to western U.S. and distributed throughout the southwest. Other species of harvester ants found in the desert southwest include P. barbatus (red harvester ant) and P. maricopa (Maricopa harvester ant), which is believed to possess the most toxic venom among insects. Harvester ants derive their common name from their habit of harvesting seeds from grass weeds.

Figure 4. Western harvester ant. Photo: AntWeb.org

The adults are dark red in color and their waists have two nodes. The workers are mostly uniform sized, about ¼ to ½ inch in length, but the queens are larger. The workers have a distinctive characteristic “beard” (Figure 4) or groups of long hairs on the underside of the head, which helps to carry seeds and nesting material. They travel in distinct trails between nests and food sources.

Harvester ants are aggressive, stinging and biting pests in Arizona landscapes. The workers can be extremely aggressive, especially when defending their nest.

Harvester ant nests are very distinctive, and consist of mounds of gravel, small pebbles or dirt surrounded by a large, cleared area, free of plants or other obstructions to prevent shade. The mounds may be up to 12 inches in height, but the nests extend much deeper into the ground, with several interior chambers. Some of these chambers are used to store seeds and other food material gathered by the foraging workers. Harvester ant mounds (our species) are usually smoother and rounded toward the top and slope gently inward at the hole in the top. The mound appears to be built of loose soil and they are usually found in very dry and bare areas. Often, the ants dehusk the seeds they collect, carry the husk outside and deposit them in a pile outside the mound (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Western harvester ant nest in Coolidge AZ. Note characteristic shape of mound and pile of seed husks (fluffy-looking material, see arrow) along the left side. Photo: Shaku Nair.

Important One-Node Ant Species

Carpenter ants are the largest ant species found in community environments. The western carpenter ant, Camponotus modoc is black in color, with dark red legs. Queens can measure up to ¾ inch, and workers from ¼ to ½ inch in length. The waist has one erect node (Figure 6). The thorax is uniform in shape when observed from the side (no spines or projections). Workers in a nest may be polymorphic (differ in appearance).

Figure 6. Carpenter ant C. modoc worker. Photo: April Nobile, AntWeb.org.

Carpenter ants can be a common nuisance pest in many community environments, and an occasional biting and structural pest. They do not sting, but can cause painful bites using their powerful mandibles. The pain of the bite is accompanied by a burning sensation due to spraying of formic acid into the wound. They damage wooden structures by nesting in them, but do not eat wood. The ants chew along or across the grain of the wood, creating clean and smooth tunnels (Figure 7). The tunnels may resemble subterranean termite tunnels, but can be distinguished by absence of soil or other termite tubes. The food of carpenter ants consists of a wide range of material, including human food.

Figure 7. Carpenter ant damaged wood. Photo: R. Werner, Bugwood.org.

Carpenter ant colonies can be formed indoors or outdoors, in weakened or damaged wood. Usually if an initial colony is first established outside within 300 feet of a building, ‘satellite’ colonies may then be formed inside the building. The initial outside nests are formed in decayed wood, such as dead trees, stumps, logs or decorative landscape wood. Once established, the tunneling may eventually extend into sound wood. The workers create galleries in the wood to allow for their movement within the nest. They do not eat this wood, but instead carry it and deposit it in piles outside the nest. These piles of wood shavings, mixed with ant body parts and dead ants are helpful to identify nesting locations (Figure 8). Indoor colonies are often built in moist, softened wood in areas were water leakage occurs. These may include porch pillars, around bathtubs, sinks, roof leaks, poorly flashed chimneys and poorly sealed windows and doorframes. When carpenter ants are spotted inside dwellings, it does not mean that a colony has also been established inside the house. They may be simply foraging for food. This is called non-seasonal foraging. Outdoor colonies typically forage during warm weather such as in the spring and summer.

Figure 8. Carpenter ant damage produces piles of wood shavings (left)-Photo: Edward H. Holsten; Closer view of wood shavings mixed with ant body parts and other debris (right)- Photo: NY State IPM, Cornell.

Odorous house ants, Tapinoma sessile (also known as coconut ants or stink ants) small dark brown to black in color. Workers are polymorphic, 1/8 to 1/16 inch in length, but the queens are larger. The waist has one erect node, which is hidden because the abdomen appears to be resting on top of the waist (Figure 9). These ants form trails, but move in quick, erratic movements when disturbed or alarmed, raising their abdomens into the air. Crushing the ants releases a pungent smell of rotting coconut. Odorous house ants are a common nuisance pest in most community environments, but do not sting or bite. These ants are opportunists and will start colonies in a variety of environments both indoors and outdoors, but are more common in indoor environments. They can be found nesting in kitchens and bathrooms.

Figure 9. Odorous house ant worker. Photo: Eli Sarnat, Bugwood.org.

Odorous house ants are often confused with Forelius ants (Forelius mccooki) because of the smell when crushed. These are very common trailing after sugar meals outdoors in the lower desert, whereas odorous house ants are more often found trailing indoors. Both have a strong distinct smell when crushed.

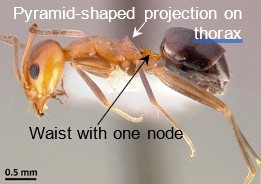

Bicolored pyramid ants, Dorymyrmex bicolor are named for their body coloration. The adults have a reddish brown head and thorax, and black abdomen. All workers are uniform sized (about 1/8 inch in length), while the queens are slightly larger. The waist has one node. Thorax is uneven in shape when observed from the side and has a prominent pyramid shaped projection (Figure 10), which also gives the ants their common name.

Figure 10. Bicolored pyramid ant. Photo: Eli Sarnat, Bugwood.org.

Bicolored pyramid ants are practically harmless, do not bite, sting or transmit disease. Rarely found indoors, as they are an outdoor species, feeding on honey dew produced by plant sap sucking insects. They move in distinct trails, and are occasionally drawn indoors by the presence of sweet food materials. Their nests are quite distinctive and are constructed in sunny, open areas free of shading vegetation. The external mounds are small and about 2 to 4 inches in diameter (Figure 11). The workers excavate the soil and deposit it around the nest entrance in a raised circular mound.

Figure 11. Bicolored pyramid ant nest. Photo: Shaku Nair.

Identify this insect.

Answer: Giant mesquite bug, Thasus neocalifornicus.

Congratulations to Master Pest Detective:

Diane Dance, Pima Co Master Gardener

(Photo by Patrick Randall)

Identify this insect.

If you know the answer, email Dawn at dhgouge@arizona.edu.

You will not win anything if you are correct, but you will be listed as a “Master Pest Detective” in the next newsletter issue.

https://uarizona.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_cMhZ82JodDKJgCa

Online April 29 – May 31, 2024

The Arizona School IPM Conference is a great opportunity for continuing education for all institutional staff engaged in operations, maintenance, turf and landscape, food service, health services and more, in schools, childcare, community colleges, public health, medical facilities, city parks and rec, turf and landscape and many other areas.

The In-Person option is now concluded. The Online option is available through May 31, 2024.

Direct links for tickets:

Conference information: https://acis.cals.arizona.edu/community-ipm/events/arizona-school-ipm-conference

For paper registration using check/Purchase Order, please email nairs@arizona.edu.

Email nairs@arizona.edu if you have questions.

____________________________________________________________

MAY 10, 2024

(In-person only)

EL CONQUISTADOR HOTEL, TUCSON

Registration and Conference Information at Front | Desert Horticulture Conference (arizona.edu)

____________________________________________________________

EPA Webinars about Integrated Pest Management

Upcoming webinar offering AZ Credits: Fungal Disease Management for Ornamental Plants. May 7, 2024 | 11:00 AM-12:30 PM Arizona time. Approved for 1.5 Arizona AG Credits only. (Please note: PMD credits are NOT approved for this webinar).

Fungal pathogens are imported into the U.S. on ornamental plants with regularity. These pathogens can have significant impacts on the ornamental plant and landscape industries. In this webinar, participants will receive an introduction to common fungal diseases of ornamental plants and their prevention and management. The origins of fungal pathogens on imported plants, their identification, as well as the causes of occurrences with plant production facilities will be discussed. Our expert will describe the importance of Integrated Pest Management, including the role of cultural practices, non-chemical controls, and the selective use of fungicides. Highlights of current research and practical control experiences will be shared.

Register here: https://attendee.gotowebinar.com/register/3726637867889702232

View recordings of archived EPA Integrated Pest Management Webinars at https://www.epa.gov/managing-pests-schools/upcoming-integrated-pest-management-webinars.

For more information about the EPA Schools program: http://www.epa.gov/schools/

____________________________________________________________

Urban and Community IPM Webinars University of California

UC Statewide IPM Program Urban and Community webinar series is held the third Thursday of every month to teach about pest identification, prevention and management around the home and garden. This series is free but advanced registration is required. Dates and topics below, all begin at noon Pacific. https://ucanr.edu/sites/ucipm-community-webinars/

___________________________________________________________

What’s Bugging You? First Friday Events (New York State IPM Program)

Fridays | 12:00 pm. – 12:30 p.m. EDT | Zoom | Free; registration required

In this monthly virtual series, we explore timely topics to help you use integrated pest management (IPM) to avoid pest problems and promote a healthy environment where you live, work, learn and play. What is IPM? It's a wholistic approach that uses different tools and practices to not only reduce pest problems, but to also address the reasons why pests are there in the first place. Each month, our speakers will share practical information about how you can use IPM. Register for upcoming events.

What’s Bugging You First Friday events are also available in Spanish. Individuals interested in these events can find more information on this website: https://cals.cornell.edu/new-york-state-integrated-pest-management/outreach-education/events/whats-bugging-you-webinars/conozca-su-plaga___________________________________________________________

To view previous University of Arizona newsletters, visit: https://acis.cals.arizona.edu/community-ipm/home-and-school-ipm-newsletters.

Acknowledgements

This material is in part funded by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2021-70006-35385 that provides Extension IPM funding to the University of Arizona. It is funded in part by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture through the Western Integrated Pest Management Center, grant number 2018-70006-28881. Additional support is provided by the UA Arizona Pest Management Center and Department of Entomology. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture or those of other funders.

We respectfully acknowledge the University of Arizona is on the land and territories of Indigenous peoples. Today, Arizona is home to 22 federally recognized tribes, with Tucson being home to the O’odham and the Yaqui. Committed to diversity and inclusion, the University strives to build sustainable relationships with sovereign Native Nations and Indigenous communities through education offerings, partnerships, and community service.